Kalisto Tanzi vanished from the city, which had been hit by a heat wave. The heat radiated from the houses and streets burning people’s faces, and the scorching town seared its brand onto their foreheads.

I stopped in front of the theater window so I could read Kalisto’s name on the posters and confirm to myself that he did actually exist. I enjoy pronouncing his name, which tormented him throughout childhood and puberty and only stopped annoying him after my arrival. I walk slowly to the other end of the city, the muscles in my legs shake slightly in the hot air. It’s noon. The only things on the planet that are really moving are drops of sweat. They run down to the base of the nose and then spurt out again under my hair.

I’m going to buy poison.

Ian saw a rat in the crapper last night.

The rat-catcher has a wine cellar underneath his store. Underground we escape the unbearable heat and drink. He’s telling me how intelligent the rats are.

“They have a taster, who tastes food first. When it dies, the others won’t even touch the bait. So we now offer the next generation of rat bait. The rat only begins to die four days after consuming the poison. It dies from internal bleeding. Even Seneca confirmed that this sort of death is painless. The other rats think their compatriot has died a natural death. But even so, if several of them die in a short time, they’ll evaluate the place as unacceptable because of the high mortality rate and move elsewhere. This gift of judgment is completely missing in some people, or even whole nations.”

A perfect, disgusting world. I smile over a glass of Gewürztraminer. The rat-catcher talks very quickly. His face is in constant motion. As if it had too many muscles in it. As if he had a herd of rodents running under his skin. From one ear to the other. From chin to forehead and back. I can feel his restless legs moving under the table and his whole torso sways in a dance.

Looking at him makes me dizzy. My head is spinning as if I were watching a film that cuts too fast from one scene to another. The rat-catcher leans toward me and gets tangled in my hair.

“You’re such a pretty little mouse . . . ” he says smiling. I smile too. I feel like I stink of loneliness.

He sees me out. On the way I get a plastic bag full of rat poison. Instead of flowers. I clutch it proudly. Maybe this is how it’ll always be, I think. If men want to court me, instead of flowers they’ll give me a bag full of second-generation rat bait.

After emerging from the cool cellar, the hot air and a world without Kalisto Tanzi hit me in the face.

*

The first time I saw Kalisto was at a gallery opening. There was a lot of drinking and during the evening a few new couples emerged. As Ian says—where there are men, women, and alcohol . . . indicating the coordinates for the location of sex.

I looked into his blue eyes and for the first time I longed for a person with colored eyes. Ian’s are almost black. Colors were always a decisive factor for me. Their combination in Kalisto’s face attracted me. We sat together and talked till morning. As it always is in the beginning, you can tell your life story again and everything sounds interesting. You talk, slowly revolving around yourself—the whole room dances with you—fine, sparkling powder settles in your hair.

In front of Kalisto Tanzi, my talking grew lively. My own life swam in front of our eyes like a glass mountain. With each word, I created it again. Recreated. I was recreated by Kalisto Tanzi. You could write a book about it, indeed! It would be a musical: Oh little fairy—if you only knew what I’ve been through . . .

But it’s already lunchtime. I’m sitting in the café. Wearing a brown dress: an old lady. I’m sitting opposite Ian. An old couple. The silence between us is interrupted only by news headlines. Ian reads them to me from time to time over the table. And then reads on. Sometimes he folds the paper and looks into my face. Our eyes don’t meet. The wine tastes like prunes and chocolate. The Coca-Cola logo on the tablecloth stealthily begins to rise toward my face. I weigh it down with a plate. I like when everything stays in its place.

At home I sit at the table and write a letter to Kalisto. Ian is standing at my back—Jeez, do you have to write such a long letter, you poor thing? Wouldn’t a text be enough? For example: Where are you?

*

Kalisto Tanzi has no mobile or email address. He considers that kind of communication threatening. (The old English expression “blackmail” referred to extorting unjustified taxes, non-existent debts, promises not given).

There’s no simple way to intervene in his life, climb through the window on the screen or display, materialize right in front of his eyes. Elza couldn’t rely on electronic seduction. Although she had a talent for it—for chatting and sweet nothings. She was a clever rhapsodist.

But the new possibilities brought her strong competition. It was so easy to get entangled with someone, to get in contact. Everything played in favor of seduction. Especially the time saved by rapid communication.

No one had to patrol a dark street at night, travel in a coach, a car, a storm. Repair wheels, change the boiling water in the radiator, march around the neighborhoods and cafés, circle helplessly in the city streets where there might be a hope of meeting the beloved one. Map the possibility of their being there. Follow, stalk, hide, stay motionless for years or journey constantly.

Emails and quick texts were windows and mirrors rapidly multiplying in the world. You could crawl through into a room, onto the roof, the bathroom, underwater, take flight. Hang your own alluring picture anywhere—an installation.

*

Elza. Into the air, in your way. Expose you to my picture.

*

Elza’s morning begins with writing. She puts on some music and works on her book intensely for half an hour. While she’s writing, she often stands up from the chair, sweating, because as she writes, she drinks liters of tea, turns the music up too loud, and writes and writes. She writes as if she were running downhill. She sweats and it chills her. Her whole life, her body temperature has varied between 37.1 and 37.6 degrees Celsius and this translates to a slight tremor and weak nerves. In addition to making you creative and passionate in bed, a fever allows you to stay home undisturbed. Doctors are usually afraid to send a patient with a fever into the whirlwind of a workday.

When she finishes writing, she’s hungry, thirsty, and has no more attention span. Elza lacks the ability to focus on creative work for a longer time—sitzfleisch. Her workday lasts three hours. When Elza rises from the desk, Ian gets out of bed. They sit together on the sofa in the kitchen and think about what to eat and what Elza will go buy. They usually eat sandwiches and drink gin and grapefruit juice. Elza read that 80% of how a person feels comes from their stomach. From what’s in it. Sandwiches and gin are food you’d associate with celebrations. That’s why whole years of her life seemed to her like one big continuous celebration. Day after day. And, as it happens during any genuinely enjoyed, seriously done celebration—at dusk or dawn, when the light is uncertain for a long time and the countryside reminds you of a theatrically lit stage set, somewhere at the root of the tongue and on the palate a decent bitter taste appears—the taste of the end of a celebration. It’s room temperature, full-bodied, with a fruity bouquet and a long tail. At night it woke her up more and more often: the taste of a sad ending. Like on New Year’s Eve when a few seconds before midnight Ian goes outside with another woman and on Elza’s chest, head, and shoulders squats a hairy troll: a nightmare, and he pisses, hot, right onto her flat breasts.

*

On the way home at dawn, Elza burst into tears in the middle of the street.

“I don’t want to march. I don’t want to keep marching on! All my life I’ve done nothing but march on!”

“Then we don’t have to walk. I’ll call a taxi,” says Ian, soothing her.

“You don’t understand. It doesn’t matter. On foot or by taxi. All we do is just keep marching on!”

*

Elza. But actually it was the marching that kept me awake. Some dealt with problems in our city by walking, others by swimming, galloping on a horse, or shooting.

“Where are you going, Elza? Aha. Just walking around, are you? Me too. But where? You don’t want to tell me, do you? I had a friend, he never wanted to tell me either. He just leaned over to me and whispered: You know, friend, I’m just on my way to the place. So you just say the same, Elza. That you are going to the place.”

It’s a small city. The minute you start off, you’ve already got most of it behind you. Someone who wants to stroll has to go round in circles—like a carousel horse—and on his way he bumps into other merry-go-rounds.

We stroll to avoid company and patiently, step by step, to evoke a feeling of freedom. In reality, we’re members of a carousel sect with rigid rules of the circle.

*

I prefer to jump into the pool. Arms and legs working like two mill wheels. My breathing gets faster, deeper, and constant. Smaller and larger pools in my head gradually fill with swimmers: alternately racing and drowning, diving and floating.

Today there are too many people at the pool. I barely avoid first the arms opening wide under the water and then the kicking legs. In the middle children stand in a circle throwing a ball full of sand back and forth. From the pool wall the fat legs of a woman exercising shoot out toward me. In the locker room a blind girl uncertainly changes into her swimsuit. My teeth go numb. As if I’ve been hit in the face with a stick.

Opposite the exit from the pool is Kalisto Tanzi’s apartment. It never leaves my gaze. This summer I’m not leaving the city. Not seeking a change of scene. Not looking for the sea. I cling to the windows of an abandoned apartment.

Ian and I meet by chance in the city. We drink wine the entire long summer evening. He tells me how he used to think that he’d somehow remember his whole life in more detail. “Whole parts, whole slabs, have disappeared. And events don’t move into the distance in a linear way with the passing time. It’s not a straight line, it’s a serpentine one. Some sections miles from each other in time come together at the bends, the curves intersect and suddenly a glimmer rises up above the surface: an arm bent at the elbow, wet hair, a fogged-up window, a mouth shaped like a circle tense on the inhale.” I tell Ian what I read today about a dangerous disease. It breaks out in middle age and the main sign is that the person begins to dance. “Then all you need is to find some good music to go with it,” says Ian.

*

Ian brought Elza to the taxi stand. In an effort to avoid another bottle of wine and a march through the hot nighttime city. He sat her down next to the driver and looked into the man’s face. He himself stayed standing on the sidewalk. He closed Elza’s door and his arms remained hanging helplessly at his sides, useless and too long. He had to take care not to drag them on the ground. Not to step on them.

*

In a moment, the taxi stops at the end of the street and lets Elza out. She jumps out like a deer. Submerges herself back into the city. Opens her arms, kicks her legs. The man on the sidewalk looks at her back as it moves into the distance and starts to dance. The orchestra’s not playing.

Kalisto Tanzi, Elza sings. That’s the name of the small, cuddly animal that’s lazily growing in me. Sings Elza. And women would like to buy it for their men and men set their eye on it. They look at me and see it, sitting inside, ripening. Sings Elza. Right on the other side of the door. And they’d like to split open my belly and break my back in two. Just so they can reach it. Sings Elza. They’d like to tear off my head and fish inside with their hands. Sings Elza. Not minding the blood: happily, even in front of the children. Elza sings.

*

Kalisto Tanzi’s apartment remains empty even after his return. He spends most of his time in the car. As a dancer at the peak of his career, he barely moves when off stage. Driving a car helps him overcome inertia. The scenery goes by at a speed comparable to when you’re dancing. The car forms the bottom half of Kalisto’s body. His back grows out of the driver’s seat. Kalisto Tanzi is a minotaur. When I approach him, I slip into the car’s interior as if into a tight embrace.

When Kalisto and Elza hug, she thinks of the warm, rubbery internal organs handed around by kids in classrooms when they learned about the human body. She and Kalisto are the pulsing innards of the dark vehicle. The car’s liver. Paired organs. Kidneys. They work all night. Warmly dressed in a car that’s cooling down. Their movements keep the vehicle alive.

*

In the morning she came back through empty streets. Washed white by a tidal wave: first it took all the houses and city with it. Then it grabbed people by the legs. And in two days it returned them: faces scrubbed by hard sand, a pearl in every orifice.

*

At home she lay down beside Ian’s sleeping face. It revealed the whole chain of appearances he had passed through in his life. Friends from childhood, an endlessly long summer, parents, a bicycle wheel peeking out from under the Christmas tree. Changes for the better as well as decay. Ian’s face was ageless. It was a restless swarm that had alighted in one place.

When she looked into his eyes, she saw all their common permutations. Every couple they’d ever been.

*

Her pain woke her up. It shot from elbow to palm and in the opposite direction to her shoulder. It agitated Elza. It was caused by her unnatural position in the car.

Kalisto ruled her life. When she walked down the city streets, she no longer looked at the faces of pedestrians, but into the cars. She was looking for Kalisto Tanzi’s driving body. Instead of the sidewalk she would have preferred to walk in the middle of the road along the yellow line between the cars.

At times her arm became quite weak. She couldn’t work with it. (Don’t panic, Elza probably thought, don’t panic.)

She couldn’t hold anything in her hand. Her fingers went numb. Her arm dried out and hung by her side like the sign of an eternal presence—Kalisto Tanzi was always at her side; when she couldn’t write with it, when a pot slipped from her fingers. If she needed the arm, but couldn’t use it, she shivered with pleasure.

She stopped eating sandwiches—only grapefruit juice and gin, apple and calvados, whisky on the rocks remained. It seemed to her distasteful to eat. To have chewed food in her mouth. She wanted her mouth to be empty and noble—prepared to receive. His mouth.

She disinfected herself with gin and at the same time it gave her the courage and insolence to meet with someone whom she liked so much. To look into the face that threatened her with what she longed for. The gin made it more bearable and livable. It was also the answer for what to do with her free time. With the inertia of the night just before dawn.

*

When Elza was desperate, she regretted never having learned to do a cartwheel. For example, she could pass the time that way while she was waiting for Kalisto Tanzi. If she could do them around the perimeter of the parking lot, her day would definitely pass faster. As it was, she just went round and round in ordinary loops.

But then she saw his car. It was sitting at the very back of the lot, that’s why she didn’t notice. She opened the door and crawled onto the seat. She turned her face, however, toward a strange man. “Honey, this isn’t the time. You can see I have my daughter in the back.” Elza turned her head toward the back and looked at the little girl sitting there. “Maybe next time,” the man said kicking her out of the car.

*

She had to tell someone.

That evening she described the event to Ian as a story that had happened to her Friend. She had saved this character of Friend. It would definitely come in handy sometime. Later, she read that lonely children who have no siblings often have imaginary friends.

*

This way, over time, Elza told Ian about the Friend, who began to behave much like Kalisto Tanzi. They had common opinions, friends, and pasts. They went to the same schools and restaurants. They read the same books.

Over time, Elza told Ian almost everything about Kalisto Tanzi this way.

*

Rebeka had an imaginary friend only during childhood. She disappeared after her first menstruation. Her name was Yp. And besides her, Rebeka took care of imaginary animals as well—one very small and fast dog, two ladybugs, and a golden horse who was completely white.

*

Wolfgang Elfman, brother of Lukas Elfman, had his animals in the forest. They were wild. So he couldn’t raise them in the apartment. He always went to them in the forest. He called to them and they came running. Then they played together and talked until it got dark.

When Lukas was a little boy, he wanted to play with them too. But Wolfgang never invited him to visit the animals. He always just told him in the evening about all the things they had done together during the day. He was excited and his eyes shone in the dark room. Lukas Elfman decided that he would find the animals himself.

“Woooolfgaaaang’s animals!” he called out in the middle of the wood. “Woooolfgaaaang’s animals!” he yelled and went deeper and deeper in.

*

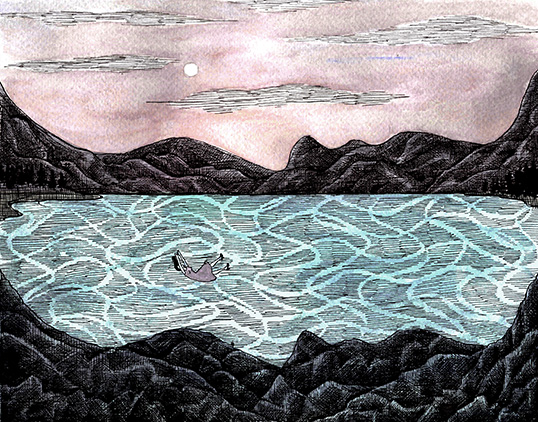

Elza plunged into the forest. After a while she stopped and turned her face toward the crowns of the trees. “Kaaaliiistooo Taaanziii,” she called. “Kaaaliiistooo Taaanziii,” she shouted and headed deeper and deeper into the wood. The crowns of the trees shone on the surface. The water swallowed movement and words. With an open mouth she hit the bottom of the lake.

(The End)