LIGHTS UP

MUMIA: Welcome to Pennsylvania’s death row. Welcome to my six-by-ten-foot cell. Welcome to the hive of shadows where every day seventy-eight bumblebees stuck in their cells sip the venom and hatred of the State. Welcome to a world where the sun can only shine two hours a day through the bars.

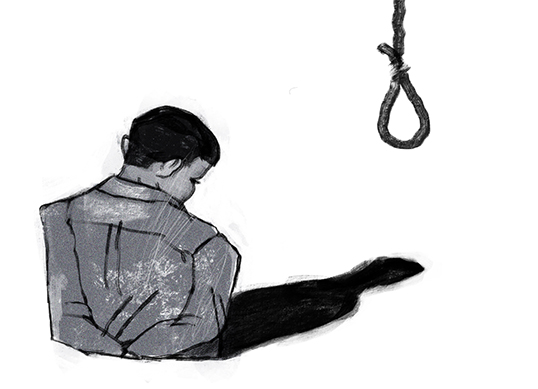

I can’t believe it. Condemned to death! They condemned me to death. Maybe I’m naive, or totally stupid, but I thought my sentence would be overturned. I really believed it. I believed my appeals would succeed. I had confidence in the justice of my country. I was a Black Panther, but I was a journalist. It’s not justice, it’s politics. A Supreme Court judge once said, “Blacks have no rights which the white man is bound to respect.” He really said that. Don’t wait for the media to tell you the truth. They’re in bed with the State. I’ll tell you the truth. Even if I have to speak to you from the valley of the shadow of death, I’ll tell it. This is Mumia Abu-Jamal, still live from death row.

BLACKOUT

SCENE 4

LIGHTS UP

CORETTA enters singing and heads towards the piano. She brings flowers that she arranges in a vase. MUMIA appears naked, upstage. We hear a voice offstage that says:

GUARD’S VOICE OFFSTAGE: Open your mouth. Stick out your tongue. Are you wearing dentures? Let me see both sides of your hands. Pull back your foreskin. Lift up your balls. Turn around. Bend over. Spread your cheeks. The bottoms of your feet. Get dressed.

(MUMIA grabs the bundle of clothing at his feet. He gets dressed and we see that he is wearing a Protestant pastor’s habit with a soft hat. As MARTIN LUTHER KING, he heads towards CORETTA, who is playing a tune on the piano.)

CORETTA: You said, “You can’t play the piano without admitting that the black keys sound just as good and are just as necessary as the white ones.”

MARTIN: I said that?

CORETTA: Yes, sir, you said that.

MARTIN: I don’t know how to play piano.

CORETTA: Don’t play dumb. Play, play for me like before.

MARTIN: You know, blind people don’t see color. Maybe that’s why they play so well (he closes his eyes). So this, this is a white one, is that right?

CORETTA: That’s right.

MARTIN: And this is a black?

CORETTA: Yes, that’s right, go ahead and play, Ray Charles.

MARTIN: Do you know what Ray Charles said to a journalist who asked him if deep down, in spite of his international success, he wasn’t secretly unhappy to be blind?

CORETTA: No, tell me.

MARTIN: “Well, it could have been worse, you know. I could have been black.”

CORETTA (laughing): Come on, play.

(MARTIN plays “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” to accompany CORETTA who sings. CORETTA continues to sing a cappella while watching MARTIN move away. She takes the bouquet of flowers.)

BLACKOUT

SCENE 5

LIGHTS UP

CORETTA is seated facing MUMIA, on the other side of the windowpane, holding the bouquet.

MUMIA: They’re pretty. Are you allowed to have them in here?

CORETTA: They gave me permission.

MUMIA: But I can’t take them.

CORETTA: I know, it’s just for you to see them.

MUMIA: I would love to smell them. What do they smell like?

CORETTA: Freedom.

MUMIA: Girls born of sunlight and water. They were dancing in the wind . . . The sun . . . I need the sun. Our skin needs the sun and the whites have thrown us into darkness.

CORETTA: Our skin is the color of prison.

MUMIA: That’s it, Mama. They want to whiten us up like chicory in a root cellar. Don’t you think so, Mama?

CORETTA: Don’t call me Mama.

MUMIA: But . . .

CORETTA: Don’t call me Mama. I’m not your mother.

MUMIA: But Martin is my father. So you’re my mother.

CORETTA: He wouldn’t have wanted to have a son like you.

MUMIA: Because I’m shattering his dreams?

CORETTA: You’re more the son of Malcolm X.

MUMIA: Okay, sure. I was born under X. We’re all born under X. Orphans of this nation. We’re all labeled X. They shut us up in ghettos because they don’t want to see themselves in our eyes. Malcolm’s glasses were X-rays. They stripped them all naked. So they killed him and shut us in ghettos, in jails, to keep themselves safe from the X-rays. They didn’t want to see themselves. They didn’t want us to look them in the eye. They didn’t want to be seen naked. Yes, I am a son of Malcolm. But of Martin, too. I am not the son of his dreams, no, I know that. His unrealized dreams. Children are never what you want them to be. A child is not a dream. I may be his deviant son, his failed son, but I am his son all the same.

CORETTA: Mumia, I am sure that he would love you as a son. And he would love Malcolm, too.

MUMIA: Yes, as a gangster son. Malcolm loved and respected him, too.

CORETTA: I know, Malcolm told me.

MUMIA: Just like me, I love him and respect him. I respect his memory.

CORETTA: Mumia?

MUMIA: Yes?

CORETTA: You can call me Mama.

MUMIA: You know, sometimes, I feel like a motherless child.

CORETTA and MUMIA (singing together): Sometimes I feel like a motherless child.

FADE TO BLACK

SCENE 6

LIGHTS UP

MUMIA alone in the visiting room.

MUMIA: This child, a ray of sunlight in my shadows. She was so little, with her little mouse voice, just like Minnie. She was only a baby when I was thrown into hell. I’ve never seen her since: she’s too young to bring here. Her eyes lit up the darkness of this visiting room! They shone with happiness. She came straight towards me, but like a fly, she bumped into the glass. Stunned. She understood, and her tears poured down. The State separated us with a window. She clenched her hands into fists and she hit at the glass, she hit and hit. “Break it, break it,” she cried. Her mother was at her side, she was petrified. But she took Hamida in her arms. She’s called Hamida. They cried and my eyes leaked and my nose stuffed up. “Why can’t I hug him? Why can’t I kiss him? Why can’t I sit on his lap? Why can’t we touch each other? Why, why, why?” I turned away. I didn’t want her to see her father cry. I caught my breath, dried my tears and turned back around. Then I told her with a grimace, “My daughter, how can you breathe with a nose full of snot?” And so, little by little, like the sun coming out from behind a big cloud, I saw her tiny smile break onto her face. It grew and grew. I reminded her how when she was little, she always used to squeeze the cat in her arms until it was choking, and her denial turned into laughter. And all three of us, we started telling all sorts of silly stories. In just a few minutes, visiting time was up. She recited the poem we would always say on the phone, “I love you, I miss you, and when I see you, I’m gonna kiss you.” We laughed, they left. It’s been five years already, since that visit, but it’s as if it was yesterday. Her little fists banging there, her child’s rage against that glass, her tears, her rage, her rage! (He strikes the glass.)

BLACKOUT

(We hear CORETTA singing.)

SCENE 7

LIGHTS UP

CORETTA singing a Harry Belafonte song:

And the song I sing,

I sing for you, sweet Martin Luther King,

And the song I sing,

I sing for you, sweet Martin Luther King.

(MARTIN appears upstage and heads towards the window pane in the foreground. He lights a cigarette.)

CORETTA: You were happy that day behind the bay window. You looked free. You were going to die, you knew it, you foretold it. It was a beautiful spring day and the birds were singing. The smell of magnolias was everywhere to cover the stench of Memphis. It was the garbage collectors’ strike. You were so happy, Martin, those beautiful Easter days, surrounded by your friends. You played with them like a child in the Lorraine Motel courtyard, playing chicken with Ralph Abernathy, trying to topple Jessie Jackson, riding on the back of Reverend Kyles. It was a Tournament of Reverends, playing like children, and whirling like birds. I wish I could have seen that. And then you went back to Room 306 and you laughed, and you laughed, and you called your mother. Why did you call her, Martin? You never called her when you were on tour. And then you gave her your love for the last time. You knew it was the last time. The sound of a saxophone floated into your room with the scent of magnolias. Ben was playing in the square. He was waiting for you to go to a night meeting. And so you walked by the bay window, you went out on the balcony, and you leaned over to talk to him.

MARTIN (leaning over the balcony): Hey Ben, don’t forget to play “Precious Lord Take My Hand” tonight, and really play it well.

GUNSHOT

(MARTIN collapses.)

BLACKOUT

LIGHTS UP

(CORETTA squatting near him, caresses him and takes out a piece of chalk to outline his shape.)

CORETTA: Why, Martin? Why did you walk past the bay window? The real world is not a dream. Death is behind the window pane, Martin. Death is behind the window pane. You always said that it could come anytime, anyplace. The sound of a tailpipe made you jump. Kyles thought he heard a car backfiring. It was a mild evening, the night was falling, and the birds were singing, do you remember?

(MARTIN gets up and leaves while CORETTA stays near his outline drawn with chalk on the black floor, and she sings:)

And the song I sing,

I sing for you, sweet Martin Luther King,

And the song I sing,

I sing for you, sweet Martin Luther King.

BLACKOUT

MUSIC

SCENE 8

MUSIC

György Ligeti’s “Lontano.” MUMIA behind the window pane as if behind a windshield.

LIGHTS RISE GRADUALLY

MUMIA: four o’clock in the morning, Philadelphia. I’m sick of being a taxi driver. That’s five dollars. Good night, sir. Shit, a gunshot. A cop is beating a black man to the ground. Fuck! That’s my brother. What did the pigs do to him? It’s okay, he’s getting up. No more. I don’t see any more. No, I see another black man lying on the sidewalk. Fuck, it’s me! It’s really me! What am I doing there? A cop is slapping my face. I don’t feel anything. Three others are coming. They’re beating me up, they’re punching me. They’re handcuffing me and pushing my head into a streetlight. The steel is hard, the steel is cold. My body’s bleeding on the pavement. I hear my daughter speaking to me.

—Daddy?/ Yes my darling?/ Why are they beating you like that?/ It’s okay, my darling, it’s okay, I’m fine./ But Daddy, why did they shoot you?/ It’s an old dream of theirs that they’ve had for a long time, don’t worry. Daddy is fine. You see? I don’t feel anything.

My father is speaking to me now. Oh, Dad, what are you doing there? You’ve been dead for twenty years./ How are you, my boy?/ Yeah, I’m fine, Dad./ I love you, son./ I love you too, Dad, but you’ve already been dead for twenty years.

Blood in my mouth. The siren wails, the car drives off. Trouble breathing. Dad, Dad, you’re still handsome. Twenty years you’ve been dead. They drag me to the station to finish me off, that’s what I think. No, they’re sentencing me to death because I killed Faulkner. Faulkner? I killed Faulkner? Oh no! The Wild Palms, The Sound and the Fury? I killed a genius?/ Idiot, not the writer, Daniel Faulkner, a cop, that’s worse./ I killed a cop? How did I kill a cop? They wanted to murder me! Their bullet pierced my lung. I’m spitting blood./ Your gun, you had it in your hand, you shot him./ My gun? But it never leaves my glovebox./ You killed him, you’re fucked, Mumia. Farewell to the Black Panthers, you’re going to burn in hell./ I’m not a Black Panther anymore, I gave it up. I don’t screw around anymore. I’m a journalist and a taxi driver./ Go burn in hell, nigger.

Fuck! This is not some stupid crime show for couch potatoes. It’s me who is behind the screen. Fucking screen. And it hurts, it’s hell. Thirty years already. Change the channel. Switch it, change me.

CUT MUSIC

And this fucking TV that feeds us bullshit all day long. We have no fucking choice but to swallow it. And we hold back time, drop by drop, second by second. Because down there, at the end of the hallway, there’s another screen, beyond the one in the visiting room, there’s a third channel, the rotisserie. So we cling to the fucking TV, we gorge ourselves on it. The world is there, life is there, behind the screen. Of course we can dream about it, but we can’t touch it. Hell is a pane of glass with people on the other side. They soften up our brains in front of the TV screen and then they cook them. Brains prepped for the electric chair. But if you want to think, or if you want to write . . . I want a typewriter. I want a typewriter. I asked for one a hundred times:

LIGHT SHIFT

(We see him in his cell.)

MUMIA: Hey boss, I want a typewriter.

VOICE OFFSTAGE: No metal allowed, too dangerous.

MUMIA: But I want a plastic one, battery-operated.

VOICE OFFSTAGE: No machines allowed, that’s the rule. For security measures.

MUMIA: And a foot-long piece of glass, that’s not a security problem?

VOICE OFFSTAGE: Where did you find that?

MUMIA: You know, on my TV set.

BLACKOUT