Other poetry comes at you like a cattle prod, unseating you. The River in the Belly, which is the latest work by Fiston Mwanza Mujila to appear in English, is full of rushing, raucous poems that won’t stand still to be admired. These are not poems meant to be read quietly and then tucked away. They’re poems that stay with you, jolting, alive.

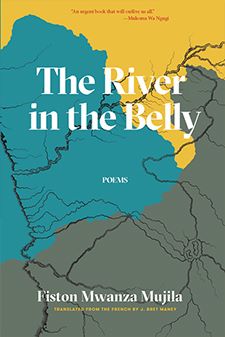

Mwanza Mujila is originally from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, although he now lives in Austria. The River in the Belly is a multilingual work, written largely in French but with words and phrases from Lingala and Swahili. The English edition, vividly translated by J. Bret Maney, preserves the Lingala and Swahili.

The River in the Belly is a series of 101 “solitudes,” pieces that range in length from just a few words to several pages of prose. Each solitude is numbered, but they are not arranged in any particular order. One-line fragments follow after longer, still-fragmentary poems and surreal paragraphs. Leafing through the book, you’ll find nausea, clacking teeth, and rotting flesh all keeping pace with a great sense of homesickness. Some readers will feel lost at first—I know I did. It helps to follow the river.

*

The river in the book’s title is the Congo River, and it meanders, in its own way, through the whole book. The poet splashes in the river, identifies himself with the river, and talks to the river. The relationship is all-encompassing and complex. The river is not a straightforward metaphor for home, or for exile, or for any other universal category. Nothing in The River in the Belly is ever allowed that level of abstraction. This isn’t some pastoral river, either. Its physicality is human, and the poet relates to it with a troubled, human love:

I brandish the Congo, the only river that saps your concentration, the only river that fakes tuberculosis, the only river that dances the tango and salsa and bolero and flamenco and the cha-cha-cha, the only river that thumbs its nose at you, the only river that eats meat . . .The river is everything and everywhere. Take Solitude 47, where the poet declares:

not blood but the Congo River

sloshes in my veins . . .

if you deny it, if you have your doubts, if you don’t believe me, pick up a sharp object (a steak knife or bayonet will do) and cut me open, slice me up, skin me from belly to belly, from head to toe . . .

This kind of language is typical of The River in the Belly. A seemingly sentimental idea—that the river of one’s homeland runs through one’s veins—is taken to its most literal, physical extreme. Violence, in the banal form of a steak knife, crops up immediately, and so does conflict between people. In this case, of course, the conflict is between the poet and his readership—the poet is challenging us to get involved. Does he really have river water in his veins? Do we really want to cut him open to check? The only options given us are belief or violence, and the poet himself is gutted.

Elsewhere, in Solitude 71, Mwanza Mujila takes a step back and looks at the river itself:

a restless, twitchy dog (?)

the river mopes as the day lengthens

it snivels without knowing just why

it’s been sniveling since Babel, since old Noah and his flood

since the prophet Ezekiel, since sister Abigail . . .

its trail of snot stretching across an absurd span . . .

The River in the Belly constantly juxtaposes the grand with the mundane. The river may be venerable, with ties to Noah and Ezekiel, but it is also a sniveling and moping figure, a lowly trail of snot. Even its great length is “absurd.” Again and again, the reader is reminded that this is no platonic ideal of a river. Nothing has been sanitized or commodified. Everything is exquisitely ordinary, from “old Noah” and “sister Abigail” to the snotty river. The river, the people, the homeland, all are painfully real, made up of flesh and fluids and unholy desires, like the poet himself:

to each their own way of grazing on life

my own, I refuse to sip daintily from a spoon

I gnaw, chew, suck, and smoke it

until it becomes feces and dust

between my uncircumcised cannibal jaws!

*

Mwanza Mujila is a great performer of his own poetry. Listen to him read, and you’ll realize that you’ve been missing a whole dimension that wasn’t represented on the page. He laughs explosively, rolling out his words to an impossible length. His voice booms. He has said that his poetry probes the line between music and literature. He cites free jazz, as well as the music of Papa Wemba and Tabu Ley, as his great inspirations.

That means that the poetry absolutely has to be read out loud. As Mwanza Mujila explained in a panel discussion at Brookline Booksmith, “for me, the text is a prison, because the words are locked in. They need to be said, to be sung, to be barked, in order to be alive, to become alive.” Poetry is expansive—it stretches language beyond its usual, utilitarian capabilities. Mwanza Mujila takes this a step further by pulling language toward music and stuffing it full of rhythm.

What does this mean for the process of translation? After all, translating means working with words on paper—moving words from one textual prison to another, as it were. If we read Mwanza Mujila’s works in translation, aren’t we even further removed from the words’ living presence?

It’s worth noting that Mwanza Mujila describes his own work almost as if he’s translating from another, wordless source of language. During the panel discussion at Brookline, the poet said that he modeled the stop-and-start rhythms in The River in the Belly on the rhythms of the Congo river itself: “In River, I tried to capture the river’s rhythm, moving against the beach, pulling a boat along, singing, rebelling, committing suicide into the ocean.” He also talked about trying to “create my own French language,” one which would incorporate the “excesses” of the Congo into the musicality of metropolitan French. Perhaps the act of translating The River in the Belly is just an extension of the work Mwanza Mujila is already doing.

*

If we cannot always hear The River in the Belly the way Mwanza Mujila would have read it—can we still understand the work? Most of us will be sitting alone with a book when we experience this poetry. Can we still unlock the words from their prison and hear the rhythms of the river, the poet’s laugh, the music of his many languages?

Some of this is a question of time, and The River in the Belly is willing to give us time. Some of the solitudes in River are a few pages long and are written in prose. They tell stories about the poet’s childhood and his family. There’s cousin Tshimbalanga, whom everyone calls Twentieth Century, and his dog Laika, whom everyone calls Acute Hemorrhoids. There’s the vendor of dog meat, and the bitter geography teacher. These stories are where we meet Mwanza Mujila’s father, a man who speaks the impeccable French of a teacher of French as a second language. They’re also where we catch glimpses of the city itself, small-time drug use and dreams of escape.

Readers who, like me, struggled to keep up with some of the solitudes at first will probably benefit from reading the longer pieces, which are grounding amid the exuberance and chaos of the shorter poems. They provide context for the oddly disembodied physicality of many of the shorter solitudes. Now we are not simply looking at a man chewing on his own possessions (“I chow down on my shirt and underclothes”)—we are pulled into his story. We know a little about his family, his friends, and his neighborhood. We can also understand the sorrow and loss pulsing through much of the book.

*

Read the whole book through, at least twice, and every poem in it becomes greater than itself. In some cases, the solitudes interconnect, providing interlapping accounts of the same events. The more we read, the fuller our pictures become.

Solitude 60, dedicated to “all the Congolese killed in Kin-la-Jungle and thrown into the river,” asks

is it my fault if the river

spits out at Brazza

the bodies thrown in at night

at Kin

in the hope of leaving no trace . . .

This is also echoed in the urgency of Solitude 102, which declares:

if I may say two words

River Congo, I won’t drink your water

as long as you keep the secret

as long as you don’t

spit out the bodies of my loved ones

at Brazza and Mbamu

Elsewhere, as in Solitude 3, the sorrow underpinning much of the book is treated obliquely. Read together with the rest of the work, poems like Solitude 3 take on an added richness:

The river’s nostalgia

Is in not knowing where to stash its pox

Not knowing what to do with its falls

It is the story of the baker who dies of hunger

The story of the cobbler who goes unshod . . .

The River in the Belly is a complex, frustrating, and ultimately rewarding collection of poems. I suggest that you read it slowly, and read it a few times. I also suggest that you resist the urge to pry open the words to find out the “meaning” of these poems. Don’t search for universal themes—if you hunt for the pure meaning of exile here, or the distilled essence of homesickness, you’ll probably be disappointed. But read this book for Mwanza Mujila’s brutal honesty and his musical language. As you read, the meaning will catch up with you.