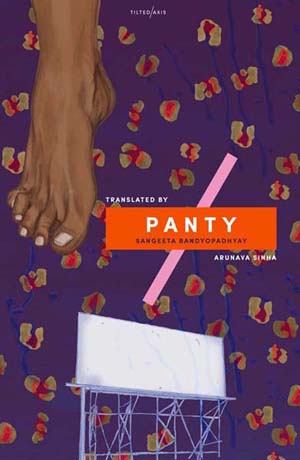

The eponymous panty in Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay’s novella—the longer of the two fictions translated from the Bengali that make up this book—is a garment without an owner. A woman arrives in a new city, lets herself into a heavily-padlocked empty apartment, and starts to live there. A day or so later, she opens a wardrobe to put away the few clothes she is carrying. That’s when she sees it. “Imported. Soft. Leopard print . . . The panty gave off the smell of moist earth. I saw a white stain on it, like mold. A stain like this in a woman’s panty could mean only one thing.”

The discovery of a soiled undergarment belonging to a stranger might produce, in most people, at least a whiff of distaste. But Bandyopadhyay’s nameless protagonist is not like most people. The thought of throwing the panty away makes her feel “a pang of regret.” From the very start, she thinks of it as more than a thing: it seems to “offer itself as a second presence in this solitary place. A feeling of companionship.” She puts the panty back carefully in the cupboard (though she does wash her hands afterward).

Two days later—during which time she appears to not have changed her undergarments—the woman comes back into the apartment late at night and finds that she’s got her period. “What was I to do now? I didn’t have a second pair of panties.” It takes very little to persuade herself that the moldy panty in the cupboard is a better alternative than her own blood-soaked one. She slips into the abandoned panty, and thus begins Bandyopadhyay’s fractured first-person narrative: a fevered dream of sex and selfhood: “What I did not know was that I had actually stepped into a woman. I slipped into her womanhood. Her sexuality, her love. I slipped into her desire, her sinful adultery, her humiliation and sorrow, her shame and loathing.”

The premise of Bandyopadhyay’s novella is contained in that originary moment, when a speculative attachment to an object offers up the possibility of a magical connection to its owner. Things are always outside of us: we produce them, and yet we grant them such power—to attract, to repel, and most powerfully, to represent our innermost selves. “A woman who wears a leopard-print panty must be quite wild. At least when it comes to sex. The question was, how wild? Wilder than me, or less so?”

The instantly comparative train of thought on which the protagonist launches herself with that question seems unutterably, depressingly female, in a way that is the result of years of social conditioning. Let me put it another way: Bandyopadhyay has succeeded in making her heroine free-spirited, sexually adventurous, unshackled to domesticity—all of which is unusual, especially for a female protagonist in Indian fiction. But just because she’s made a point of not running the Good Girl race, must she necessarily contest the Bad Girl one?

The protagonist is a woman with a compromised present—her lover is willing to sleep with her, put her up in a house he owns, and perhaps even help fund her medical treatment, but not to commit to or even publicly accept their relationship. She also has a compromised past that returns occasionally to haunt her: a child who died in an accidental fire while she was “far away, lying beneath a man [she] barely knew.” (The guilt of a mother about neglecting a young child—leaving him locked away in a room all day, while she goes to work as a rich man’s companion—is the dominant theme of another of Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay’s novels, Abandon, due to be published by Tilted Axis in 2017.)

In another recurring thread, she watches a homeless family live out their lives on the pavement in front of her apartment, becoming fascinated, then attached, and then bizarrely covetous of their little girl, for whom she sometimes takes down a packet of food. “I’m surprised at the way her eyes sparkle with intelligence. At such times, I long to take her away, to teach her to read and write. To give her brushes and paints. To teach her Rabindranath’s songs . . . ” This feeling is exacerbated when a “foreign woman” appears on the pavement, creating the suspicion that she is going to take the child away. So anxious is she about this that she even stops taking food to the child, surrendering instead to bucolic dreams in which she is the child’s mother. (This theme, of a childless upper-middle-class woman playing at motherhood and social responsibility with the child of a much poorer family, was recently explored in a sharper, more ironic register by Parvati Sharma’s 2015 novel Close to Home.)

If Bandyopadhyay allows her heroine a great degree of political incorrectness with regard to class and race, she takes even greater risks when writing about her response to the visible religious identity of her co-passengers on a journey. “The blood in her veins had been quickened by the fact that she was the sole representative of her faith on this bus—much more so than by her being the sole woman. Was her religion then a stronger and more primal factor than her womanhood?” Most frequently, though, it is in the sexual domain that the book seems to want to shock. A recognizable Bengali poetic-romantic register is made to coalesce with graphic descriptions of sexual acts:

She felt tears welling up again, and allowed them to fall one by one into the lips of your penis, like individual strands of pubic hair. And she began to torment it. It trembled, made you tremble too, and an introspective, penetrating stream spurted from it. Which she had never observed as closely as she did now. Never looked at, never touched, never sniffed, never tasted. Her consciousness accepted this liquid. She drank the sperm.

The panty is only one among the anonymous objects that stir her sexual passions. In one of the book’s disconnected (and randomly numbered) chapters, she is walking down a street in the city when she realizes she doesn’t know where she is. It is at the same moment that a power cut strikes. Bandyopadhyay’s description is vivid, if a little too dramatic: the power cut “swooped down like a black panther, gobbling up the lane. Everything was annihilated by the killer paw of darkness.” And then she is—or imagines herself—kissed on the lips by someone she cannot see. Only her lips are touched—“the rest of her remained untouched and absolutely free.” Her lips are “bitten and mauled,” but “She was hooked.” “[A]s she turned the corner onto the main road, the meaning of 'illicit' became clear to her,” writes Bandyopadhyay. “She had returned to the same lane many times since then, always just as dusk descended. There she would stand still and wait for the lights to go out, for a kiss to swoop down on her.”

This constant yo-yo-ing between pleasure and guilt, freedom and dependency might be said to form the unstable bedrock of Panty. Even the sex—and there is quite a lot of it—has a hunted, haunted quality.

On the book’s blurb, the author Niven Govinden compares Bandyopadhyay to Elena Ferrante. Certainly there is something to be said for the fact that both authors give us a certain rare sort of woman protagonist—the kind who wanders the streets of an inhospitable city, an often dissolute flâneuse. Ferrante’s first novel, Troubling Love, also put used women’s lingerie at the center of its stifling psychological mystery—a too-new, too-seductive lace bra is found by a daughter on her dead mother’s body; a man who fetishistically collects the mother’s worn underwear ends up with a pair of the daughter’s blood-stained panties. But where the compulsive wanderings of Ferrante’s Delia derive their excavatory power from the remembered stench and secrets of a childhood hometown, Bandyopadhyay’s heroine seems to be floating through both space and time. Her childhood memories—featuring snakes and lice as sexual symbols—are oddly overblown, and the city seems entirely tangential to them. Instead of a densely signposted Neapolitan streetscape, we get a Kolkata that remains an “unknown city,” only barely evoked by specifics: an occasional “Park Street” or “Victoria Memorial.” Otherwise we must be content with the amorphous vagueness of “the club,” “the tall apartment building,” “the ghat,” and a nameless “she” who in fact spends most of her time cloistered in the empty flat, losing her mind as she lives through suffocating sexual fantasies brought on by a painted-over mural—a premise that might well be a reworking of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1890s feminist classic “The Yellow Wallpaper. ” Another critic has compared Panty’s mix of real and surreal to a Robbe-Grillet novel.

The short story “Sahana, or Shamim,” which makes up the rest of the volume, is a startlingly visceral tale of a woman whose return to eating fish behind her vegetarian husband’s back ends—or so she thinks—in tragedy. Sacrificing logic and narrative closure for a sly self-referentiality and a direct address to the reader, Bandyopadhyay made more of an impression on me with these few pages than she did with the self-consciously soulful Panty. The mystery and ellipticality that seems so deliberately cultivated in Panty appears spontaneous here.

Arunava Sinha, who is currently perhaps India’s most prolific literary translator, has produced a text that retains much of the author’s poesy. It is a style that has a certain lushness and emotional purchase in Bengali, but can sometimes appear long-winded in contemporary English. For instance, this description of a wandering young sanyasi (mendicant): “If you felt it was impossible to join him, no explanation would suffice—such was the language of his eyes. No one joined him, only offered their respects. That dawn, it was he whom I identified as my nation.” And immediately after: “Accusing others, complaining, using my heart to sear another’s heart, searing it with memory, using my body to set theirs on fire—such activities had been my main occupation for a long time now.”

Another thing that struck me upon going back to Bandyopadhyay’s 2006 Bengali original was the fact that the book “translates” even Bandyopadhyay’s English. Some of these replacements are country-specific, such as “ensuite” where the original text said “attached bath.” But another set of changes seem to me to rob the text of a layer of meaning. Bandyopadhyay peppers her Bengali dialogue with English. For instance, the protagonist’s lover says to her on the telephone: “What the hell you are saying woman?” In the British edition, this becomes “What the hell are you talking about, woman?” (p.40). In “Sahana, or Shamim,” a sentence of dialogue originally uttered in English—“I can’t enter in a body which is some way or the other fishy”—becomes “I can’t enter someone who is, in whichever sense, fishy.” The unhesitating (if sometimes ungrammatical) use of English words and sentences marks the narrator and her lover as a specific variety of upper-middle-class Bengali-speakers. Keeping them as they were, and gesturing to the fact that they appear in English originally, would have allowed the British reader access to the English-flecked world of the Indian elite.

Perhaps this response betrays me as belonging to what Janet Malcolm, writing recently in the New York Review of Books about two approaches to translation, has called “the more advanced (or masochistic) school who want to know what the original was 'like'.” On the whole, Sinha’s unfussy translation ought to appeal to Malcolm’s second kind of reader: “the reader of simple wants, who only asks of a translation that it advance rather than impede his pleasure and understanding.” But there is at least one instance in the book when explanation precedes—and brings about—the presence of a word.

At one point in “Sahana or Shamim,” the Bengali text reads “jokhon taader aalaap hoyechhilo, kotha deowa-neowa hoyechhilo.” This might translate to “when they had first met, given each other their word.” But Sinha does something curious. He inserts a Bengali word that wasn’t in the original. The text reads: “when they first met and exchanged mōn.” On page sixty-three of Panty, too, in the phrase “dhormo hridoybritti noy,” the Bengali word “hridoy”—meaning heart—has been replaced by “mōn.” “Religion wasn’t born of the intellect, it wasn’t a pursuit of mōn,” writes Sinha.

“Mōn” has appeared at the very start of this edition, in a note in which Sinha explains that “English-reading people” think of the heart and the mind as a binary, but that this Indian language word allows us to take a position “on a continuum between the heart and the mind, between emotion and knowing, between feeling and reason.” Instead of a mere translation, the text here seems keen to offer “English-reading people” an alternative culture of selfhood. I’m not sure where my mōn stands on that.