A spirit of philosophical resignation breathes life into the characters of The Sad Part Was and animates its narratives with both sorrow and hope. The book is filled with a buoyant emotional tenor but also suffused with a sharp sense of the preciousness and fragility of life. This paradox is a corollary of the religious precept of ploang, a verb described in the front of the book as meaning “to put something down, to unburden, to be at peace with letting go . . . a Buddhist approach for dealing with adversities and disappointments . . . a Thai recipe for contentment.” The collection shows considerable thematic consistency throughout its twelve stories, all of which portray contemporary urban Thai life. The Sad Part Was captures the zeitgeist of 1980s and ’90s Bangkok, but it also considers the present moment as a site where contending social forces collide. What’s more, it summons contrasting aspects of the human spirit to allegorize the perennial problems of artistic creation. Reading The Sad Part Was, we delight in the work of an accomplished literary artist.

Stories whose theme is urban modernity often account for a concomitant forfeiture of traditional values. Modulated approaches to this reckoning are the exception, however. To see how far Prabda Yoon’s work stands from idealized views of cultural heritage, we might compare the opening story of The Sad Part Was, “Pen in Parentheses,” with “Grandma,” a 1962 piece by the Thai poet and visual artist Angkarn Kalayanapong (1926–2012). Both stories relate the transition between generations, but Kalayanapong’s old woman communes with the universe by speaking with the plants and animals that welcome her into their embrace as she dies. Yoon’s old woman, on the other hand, is a social being, participating with her grandson in the collaborative project of ejecting the past. When the young man says, “I made this commercial especially for you and Grandpa,” she appears to ignore the screen, her eyes “fixed on me, on my face, as if I were an old movie she hadn’t seen in a long time.” As the text is at pains to make clear, her lack of interest in the ad can hardly be attributed to a strict adherence to traditional Thai culture, narrowly defined:

My grandmother watched my Dracula Meets the Breath Mint commercial with a smile . . .

I asked if she heard the Mozart in the movie. She looked surprised: Was Mozart in there? I nodded: Yes, the “Turkish” and the “Jupiter,” the ones you always played as the soundtrack for Dracula. The one with Bela Lugosi, that Grandpa used to screen on Friday nights. She said: Oh yeah? I didn’t hear it. I’m old, sweetheart. My hearing’s not what it was. I wanted to rewind the tape and show the movie to her again: Grandma, listen closely. She said: There’s no need. I believe that Mozart is in there, just like you said. We don’t have to watch it again.

The fortitude of the old, in summoning the strength to cede place to the young, intermingles here with a natural deference on the part of the young. The two together express a mutual, reluctant ability to relinquish obsolete modes of life in order to go on living.

This rare intricacy and subtlety in a treatment of conventional tropes can also be seen in “El Ploang,” in which a young man sitting on a park bench befriends an old man who can see into the souls of passersby. El Ploang declares the narrator to be a good person, but will not divulge to him what the reader already knows—that the protagonist is good because he recognizes the perennial place of evil in human life. The narrator confides to us that he takes ethics more seriously than a religious dogmatist could. He never expresses his views socially, and it’s their intricacy and inwardness that add moral depth to his character.

Evil is the mother of opportunity. Good would never be that creative. Evil is art and entertainment; good is bland and boring.

Why should I care if I’m going to heaven or hell? Both places are founded upon beliefs that are fading over time. Evil teaches people to stop being hung up on superstitions. It teaches us to learn to live life fully here on this earth. Even if you’re condemned to boil in hell’s cauldron or drag your naked body up the adulterers’ thorny tree, you’d be sharing in those activities with your fellow sinners. It’s no different than going on summer camp. Everyone would rather meet the Guardian of Hell than God, because the Guardian of Hell is humanity’s true teacher, covertly indoctrinating us from the cradle. He stands close by us when we want, when we hurt, when we ache, when we love, when we lust, when we hate, when we obsess, when we’re hungry, when we’re greedy, when we’re angry, when we’re vengeful.

God only watches from afar. He never lends a helping hand.

“El Ploang” is remarkable in its eschewal of irony: the protagonist harbors views that would verge on the antisocial if he gave vent to them, and yet he remains unaware that his reserve is precisely what makes him good—while the author maintains an indulgent distance from his unselfconscious character. This story depicts a contemporary form of decorum, open and without uptightness.

The Sad Part Was forfeits such nuance, however, when youth, confronted with less hospitable company, poses an affront to the legionnaires of respectability simply by going about its business. In “Something in the Air,” for example, the perfume of a young couple’s postcoital bodies incenses a police officer despatched to investigate a crime, and he takes them in for questioning for no other reason than that they’ve just had sex:

But what my squad and I found utterly revolting was your shameless conduct. Even with a dead body lying there on full display, drowning in a puddle, you still felt the need to stage a love scene, in the face of a fellow human being’s death. If the nation’s young men and women are all as lacking in decency as you, our future will be dark and dismal indeed. As a person of more advanced age, I’d like to express my sincere disappointment at the moral collapse of the younger generation.

The publication of The Sad Part Was coincides with a London Book Fair screening of Yoon’s 2016 directorial debut Motel Mist—whose producers, TrueVisions Original Pictures, briefly withheld the film from Thai distribution immediately after its domestic premiere late last year due to the picture’s sexually suggestive content. Although the Minister of Culture’s Censorship Board had approved the production as appropriate for viewers over eighteen years old, there remained considerable timidity in Thai entertainment circles following the death of King Bhumibol Adulyadej—“scenes of actresses waving around sex toys and other sexual references were its undoing,” the news site Khaosod English prematurely opined. It is interesting to note that such prudishness was completely absent from the reception of the book from which most of the stories in this collection were drawn—at least as far as this reviewer, who does not read Thai, has been able to discern. In fact The Sad Part Was made Yoon a household name, and had a revolutionizing effect on Thai writing. Yoon denies that his fiction and his filmmaking are connected, and indeed it may turn out that the distinct life of Motel Mist will take it on a parallel course, changing the movie game in Thailand much as The Sad Part Was changed the story game. It may not be irrelevant, however, to suggest that what Yoon’s films and books have in common can be seen in passages like the above, where the Bangkok of twenty years ago is characterized as a period of rapid transition from old to new.

In “The Disappearance of a She-Vampire in Pattaya,” rumor runs amok when Rattika goes missing. The gossipmongers guess that the young undead fugitive has a reason for running away: she has a son, and wants to protect him and provide for him. Rattika becomes an absent stand-in for the dreams of the people she has left behind. She is also the scapegoat of their resentment:

But if the bar girls were right, the story would have had an entirely different outcome, one in which Rattika and her son lived happily ever after, or at least were happy right now. If Ken really existed, as the bar girls were convinced, he would be a half-blood—half vampire, half human. Such things were considered scandalous in Thai circles, so the girls didn’t dare raise their voices when they mentioned it. But they whispered, among themselves, and what they whispered was that Ken’s father was a monk.

This playful description of anti-vampire prejudice among Thai people is understood as a subtle but thinly veiled take-down of Thailand’s provincial and insular mindset (an assertion, incidentally, which Yoon corroborates in a remark on the state of Thai publishing: “There is little interest in Thailand to read books from other cultures other than the big bestsellers from the UK, the US and possibly from Japan,” he notes in Publishing Perspectives). In a sophisticated interpretation of the vampire genre, then, “The Disappearance of a She-Vampire in Pattaya” thematizes culture clash by turning the local vampire community into a metaphor for any fringe group, allowing us to contemplate its dynamics for their own sake.

More significant than the book’s self-conscious interventions into such well-defined genres as vampire fiction is its sustained exploration, primarily through allegory, of the process of artistic creation. “Marut by the Sea,” whose protagonist openly revolts against an absentee author named Yoon, presents a conventional foray into this territory. More compelling is “The Crying Parties,” in which friends gather to eat chillies that make them cry. The tears are in honor of an absent member of the group, their leader June, a recent suicide who inaugurated this unusual tradition “as a way to detach crying from sadness . . . to train herself to cry for amusement.” June’s unusual pastime is an elegant metaphor for our need to make and experience art, and for art’s role in inviting the cultivation of aesthetic emotions that ease the suffering of human beings living in the knowledge of death. The relationship between artist and audience member, and between muse and artist, is the theme of “Miss Space,” in which a glimpse of the flatfooted yet mysterious Miss Wondee writing in her journal on a city bus occasions a seriocomic stream of conjectures from the narrator. The wide spaces between lines of handwriting in her journal fascinate him. In classical fashion a silence between two smiling strangers is broken and the inspired narrator addresses the source of her creative impulse:

The frequency with which you expel carbon dioxide and draw in oxygen probably forms a graph with peaks and troughs that resemble a series of elongated hills. This gives you more distance for reflection, i.e., space for thought, than the average person—about ten seconds’ worth. Hence the spaces in your writing, which leave room for reflection.

This conversation galante is a figure for certain phases of the creative process. First, the gaze of the everyday muse replaces the “divine afflatus,” the breath of the goddess whose influx fills the writer with the need to write; he then breathes out the spirit with which she inspired him. Second, inasmuch as the narrator reads Miss Wondee’s journal, he is also a reader, and the story is therefore also a metaphor for reading: he absorbs the work of those who remain inscrutable to him, and it nevertheless moves him to produce work like theirs. In many ways this story is Yoon’s declaration of artistic intent: he aims to create artworks that leave room for the reader or viewer to take part in making them.

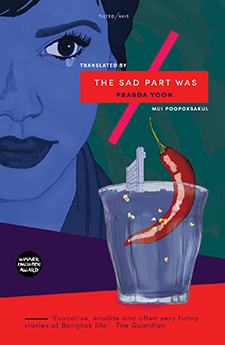

With her English version of The Sad Part Was, translator Mui Poopoksakul achieves a success that we might sum up in two ways: first, she creates a new English tone that carries the narrative voices of these stories over with an enviable grace: “When the wind caught her long black hair, it streamed out behind her like a piece of the night sky had come undone.” Second, Poopoksakul discovers several inventive solutions to the problems of rendering Thai figures of speech into English. For instance, when the young couple in “Something in the Air” are impugned, not by anything they’ve done, but by their flagrant disregard for propriety, as evidenced by the intermingled fragrance of their flesh, Poopoksakul compresses these two ideas into the lovely phrase “the flagrance in the air.” In an elegant afterword, she describes aspects of recent Thai history: “the lightness of the national mood made experimentation in form possible,” she writes, “as the need to convey ideological messages faded into the background.” Those days are gone for good, and will never return, except perhaps in a Prabda Yoon story. Thanks to Mui Poopoksakul, they now live on in English too.