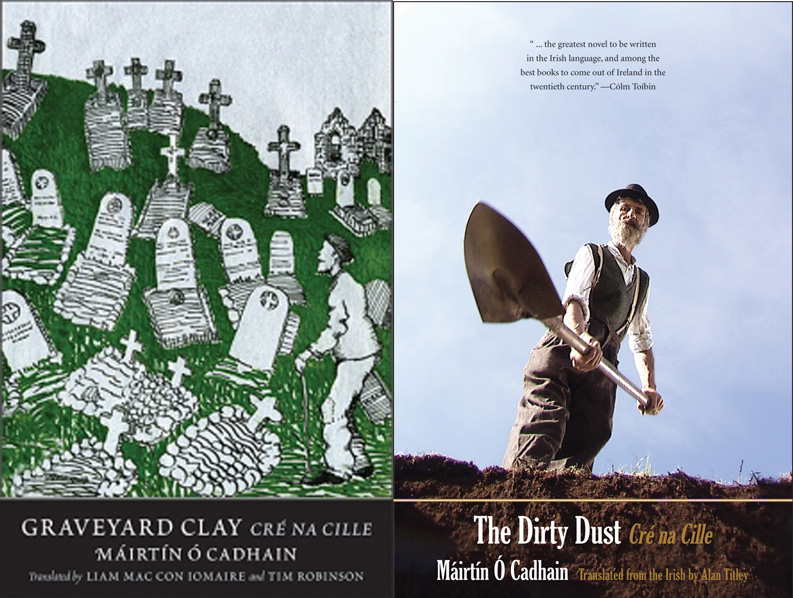

The timing of these two translations is not as surprising as it seems. Rather, the coincidence is the product of two trends: the revival of the Irish experimental novel, as evidenced by the recent success of writers like Eimear McBride and Mike McCormack, and a renewed interest in Irish, by which I mean Irish-language, writing. What is more fortunate is that the two editions take different approaches to the original. It is often said that the act of translation always reveals ambiguities in the source text. Comparing translations also reveals ambiguities in the act of translation. And the questions that translators must answer—who is this for? should authenticity or ease of reading be given greater weight?—are also the questions faced by activists for the Irish language.

*

I am currently learning Irish. Specifically, I am learning to translate Irish, because I am working on a writer called Brian Ó Nualláin (also known as Flann O’Brien and, in the columns I’m writing about, Myles na gCopaleen) who wrote across two languages. The process of learning for translation is strange, not least because any classes focused on the written register of a language tend to begin at an advanced level. I think of the Bröntes, learning German by sitting around the fire with Goethe and a dictionary, and download a PDF of Dinneen’s 1904 Irish-English dictionary. Then I remember Ian Duhig’s poem “From the Irish,” which is also about the problem of learning languages in a written register:

According to Dinneen, a Gael unsurpassed

in lexicographical enterprise, the Irish

for moon means ‘the white circle in a slice

of half-boiled potato or turnip’. A star

is the mark on the forehead of a beast

and the sun is the bottom of a lake, or well.

Well, if I say to you your face

is like a slice of half-boiled turnip,

your hair is the colour of a lake’s bottom

and at the centre of your eyes

is the mark of the beast, it is because

I want to love you properly, according to Dinneen.

Duhig was the first of his brothers and sisters not to be schooled in the medium of Irish, and, afraid of the secrets his siblings were whispering, tried and failed to learn the language on a Gaelic League course. “A bad workman,” he explains, “I blamed my tools”: “Dinneen’s is the classical dictionary of Irish, but it rather records the use of Irish words as he felt they should be used, as he felt would be the pure use, rather than the way they were used.”

I put aside Dinneen, and go to Donegal to attend a language school. Every morning, a group of us—six Americans, three English, a Japanese woman—assemble in our classroom with notebooks and pens, laughing about how we feel like we’re back at school. None of us have anything like what you might call a natural affinity for the language. We struggle our way through all the usual topics of language learners: where we’re from, what we like to eat, our clothes, our hobbies. We learn how to order a drink, and try it out in the evenings at a pub named Roarty’s, where we also teach the Americans (college students, and too young to drink back home) about the rhythm of ordering in rounds, getting them wrecked on Jameson and ginger ale. Every night I practice vocabulary, write my shopping list using newly acquired words: arán, prátaí, bainne, uibheacha. Irish phrases start to crop up in my dreams. Back in the office in London, I start every morning by listening to Raidió na Gaeltachta through headphones. My colleagues ask how the Irish is going, and I tell them it’s going better than I thought it would. (They are either too distracted or too polite to point out this does not mean “well.”) Slowly, I become proficient enough for the news program, and then for the very simplest of na gCopaleen’s puns.

Linguists tell me it is ridiculous to say one language is harder to learn than another. Perhaps it is similarly meaningless to say the politics of a specific language are especially fraught. Yet the status of Irish in Ireland is undoubtedly more controversial than the status of French is in France, or, indeed, the status of English in England. The bones of the situation are thus: Irish is believed to have become a minority language during the nineteenth century when Ireland was a British colony. The introduction of the National School system—taught in English, by order of the British government—and a series of famines drastically reduced the size of Irish-speaking populations on the island. Even after the establishment of an independent Irish state in 1922, government services remained in English, even in the gaeltachtaí. A 1926 Gaeltacht Commission sought to implement measures to combat language loss, yet its recommendations were ignored, and the state remained a force for Anglicisation well into the second half of the century.

Though campaigning bodies in both the literary and political spheres had some success in widening access to the language, the ease with which speakers could conduct their lives solely through Irish continued to diminish. The last generation in which monolingual speakers numbered more than 5% of the population are believed to have been born between 1825 and 1850, and although the number of those with knowledge of Irish grew post-independence, the number of first-language speakers fell. Today, it is not only the number of Irish speakers which is a concern, but also how the language is used by those who have it. In 2012, the academics Georg Rehm and Hans Uszkoreit published a book entitled Irish Language in the Digital Age, in which they observed that “for the broader population, a considerable gap exists between levels of ability and usage, with the latter much lower.” Or, to put it simply: Irish is more known than spoken.

Translating Irish thus poses a number of common translational questions with unusual urgency. The tension between different registers of spoken and written language, for instance, has a particularly fraught history in modern Irish. Taken up by prominent poets and playwrights as part of their struggle for a national republic of letters, public appeals for Irish during the first half of the twentieth century were often also appeals to a Revivalist version of literature, which stressed poetic heft first and foremost. Many of the most visible agitators for the language, Pádraig Pearse and Eoin MacNeill among them, privileged certain poetic registers of Irish over everyday spoken ones, invigorating a carefully-assembled bardic tradition while neglecting a vernacular one. It is this backdrop that makes Ó Cadhain’s novel so radical and so significant for the history of Irish writing. In fact, he has his characters mock the Revivalist version of Irish, saying of a language-learner who wants to study a graveyard dialect that “a few of his words are ‘Revival Irish,’” so “he has to unlearn every syllable,” adding that

—He also intends to collect and preserve all the lost folklore so that future generations of Gaelcorpses will know what sort of life there was in the republic of Gaelcorpses in the past [. . .] He thinks it will be easy to make a Folklore Museum of the Graveyard and that there will be no difficulty in getting a grant for doing that . . . (Graveyard Clay)

In a period where prominent figures appear more interested in ossifying a linguistic past than encouraging the evolution of a language, to insist on the legitimacy of the base, the ugly, and the banal, as Ó Cadhain does, is its own act of insurrection.

*

In this sense, The Dirty Dust is closer to the spirit of the original than Graveyard Clay is—although there is no doubt that Titley allows himself certain liberties in translating Ó Cadhain’s text. The purple prose of the Trumpet of the Graveyard—the voice that heralds new arrivals—is made less literal and more overwrought in his version: “Every cloud lenites the purple capital letters of the pirouetting peaks of the mountains” as opposed to “each cloud is a glorious dot of lenition on the purple capital letters of the peak tops” in Graveyard Clay. Similarly, where Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson leave blasphemous references to the devil largely intact, Titley replaces them with obscenities that a contemporary readership would recognize as equally offensive. Thus Ó Cadhain’s “T’anam cascartha ón diabhal, cé thú fhéin?” is rendered by the former as “the devil take your rotten soul, who are you?” and by Titley as “for fuck’s sake, come on like, who are you?”. Similarly, “smuitín”—“snouty”—is “pussface” in Graveyard Clay but “bitch” in The Dirty Dust.

What Titley’s simultaneously stronger and freer language sacrifices in accuracy, it makes up for in effect. Cré na Cille is an intensely verbal novel, situated almost entirely in an oral register—a fact Titley stresses in his introduction when he writes that in the Connemera of the thirties and forties, with no cinema or television, “the only culture was talk. There were songs and music and some dancing, but talk was the centrepiece of creativity.” We speak very differently from how we write: not only less formally, more imprecisely, but also more freely, because the impermanence of conversation allows us to say things we would not dare put in writing. Ó Cadhain’s novel takes this principle to its ugliest and funniest extremes.

The ugliness is particularly important. Tragicomedy is a mainstay of the Irish literary tradition, particularly as it intersects with the everyday. It is precisely because Cré na Cille’s characters are deceased that they distil this aspect of life to its essence: Ó Cadhain teaches us not only that the petty concerns of the living endure beyond the grave, but also that the grave is a place where we are nothing but our petty concerns. In this extreme version of Connemara’s already relatively isolated oral culture, characters are left to rake over their lives without the distractions of work or movement. (Ironically, to recreate this sort of community in today’s digital age, you would be forced to set your novel in the graveyard—for this reason, the novel has not aged as badly as other prominent Irish-language writing from the period, such as Tomás Ó Criomhthain’s The Islanders.) “Joyce,” na gCopaleen wrote, “was a great master of the banal in literature. By ‘banal’, I mean the fusion of uproarious comic stuff and deep tragedy. For in truth you never get the one without the other, unless either be fake.” Ó Cadhain’s novel operates via a similar series of contrasts: between the sacred and profane, the stagnant and bolshy, and, yes, the sad and funny. It is crucial that the cast of Cré na Cille blaspheme—the only question is whether they ought to do so according to the mores of 2015 or 1949.

*

Where Titley’s anarchic, freewheeling translation, aimed at capturing the irreverence of the original text, speaks to the political moment in which Ó Cadhain was writing, Graveyard Clay is aimed at today’s. At times, it resembles the Norton student editions of texts that were assigned undergraduate reading when I was at university, footnoted to a patronising degree. Its introduction is bumpy with brackets: Gaeltacht, we are told, means “Irish speaking region”; on the next page, we are told that Gaeltacht can also mean “Irish-speaking” when applied to a community of people. And if there is any doubt that the reader of this text would have trouble with the word “turf”—or lack the means to look it up—then “(news)paper” is undoubtedly an unnecessary clarification. Its adherence to the original means the body of the text also contains snags: aside from sometimes off-key anachronisms like “pussface,” retaining and then explaining terms like “Friday’s King” (footnoted as “Jesus”) serves as a distraction (indeed, possibly more of a distraction than confusion would be).

While these moments are jarring for the reader, however, they are likely helpful for the students whom one presumes make up the bulk of the intended readership—and particularly helpful for anyone working between the original and a translation. The importance of this is not to be underestimated. A lot of language activism is pedagogical; after all, there is no point having Irish (or Cornish, or Welsh) on road signs and in government documents if the population can’t read it. In the Republic of Ireland, every school student must complete an Irish requirement in order to gain their Leaving Certificate. Theoretically, this means that almost everyone will leave school with at least a basic knowledge of the language. In practice—or so I gather from the women in my language classes—students are often put off by their schooling, letting their skills lapse soon after graduation. “A normal ‘age pyramid’ for a declining language,” Reg Hindley writes in his cheerfully-named The Death of the Irish Language,

is broad at the top, with strength in the upper age groups, and pointed at the bottom, with weakness in numbers and proportions among the young. In the Irish census it is broad at the bottom, in the school attendance years, and tapers sharply upwards as ‘school-Irish’ is forgotten.

“School-Irish” is not particularly well suited to daily use, even when one learns it as an adult, and so it is perhaps not a surprise that relatively few of those who acquire it invest in its upkeep. Increasingly, language activism in Ireland takes this into account: apart from research, such as that cited above, which specifically considers how to refashion Irish for the digital age, language initiatives often select a practical focus such as liaising with employers to increase the use of Irish in the workplace, or improving take-up among Protestant communities in Northern Ireland, where the Irish language has frequently been linked to Republicanism.

In this sense, Graveyard Clay is a timely intervention in a canon desperately in need of radical writing in translation. The decision to retain the Irish versions of character names in the text is just one example of how Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson’s translation might more readily lead one toward Ó Cadhain’s original. Titley calls the graveyard’s most vocal resident Caitriona Paudeen, but for them she remains Catríona Pháidín, which, we are told in the list of characters, means “Catríona (daughter of) Páidín.” Similarly, the Celtic-inflected quirks of Anglo-Irish grammar and the inclusion of words like “misha” are enjoyable for the language learner who can appreciate their roots, even if the result of these features is that the dialogue of Graveyard Clay does not flow as readily as that of The Dirty Dust. For readers with no knowledge of Irish, the texture of Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson’s prose is pleasingly resonant of another time, particularly during moments of conflict, such as when Catríona learns that another section of the graveyard has won the burial ground’s election:

What’s that shouting, Muraed? . . . The Half-Guinea crowd . . . Celebrating the election of their candidate. They’ll deafen the graveyard. The beggars! Thieving ill-mannered rabble! Oh, do you hear the goings-on of them! God bless us and save us! It’s a poor plight to be in the same cemetery with them at all.

If the footnotes suggest that Graveyard Clay does not always trust its readers to traverse the gap between their own world and that of the text, at least it does not try to narrow the distance.

*

So which, then, is better? My partner, more fair-minded than I, made the point that really you need both to exist—the accurate and the freewheeling. Certainly, if you believe that genius—and Ó Cadhain’s text is genius—deserves as loyal a tribute as possible, then it is hard to begrudge Mac Con Iomaire and Robinson their sometimes over-literalism.

Yet there is also a case to be made for pleasure, which is not as cheap a goal as much writing on translation might have you believe, and Titley’s translation seems to me the better read. I must admit that I’m also seduced by the idea of a writer sticking two fingers up at po-faced Revivalists, and glad that The Dirty Dust will likely irritate the same enclave of bores irritated by the original. Readers of Graveyard Clay will trust that Máirtín Ó Cadhain is a good writer; readers of The Dirty Dust will know he is a great one.

Accuracy is a noble aim, but it is perhaps not always worth the trouble (and this text gives the translator as much trouble as possible). If a translation cannot be accurate on the level of the word—even beyond the degree most translations cannot be—then is it not better to privilege accuracy on the level of the text; to avoid Duhig’s Dinneenian problem, and plump for meaning over matter? My recommendation, then, is for Titley’s translation: the better at getting across the manic energy and bitchiness of a novel whose author, one hopes, is down there somewhere hearing Caitriona say “bitch.” I don’t believe Irish is dead, but if it is, its afterlife ought to sound as ribald as possible.