It was all wrong, of course. The major sticking point was that ‘Gwangju Elegy’ completely lacks the neutrality of ‘The Boy is Coming,’ which, as with all Han's Korean titles, deliberately offers no clue as to genre or moral judgement (even more crucial with a book like this, which consistently and necessarily avoids any hint of didacticism). And the tone wasn't in fact remotely elegiac, in any of its parts. As in The Vegetarian, each section has its own very distinctive tone and atmosphere, producing an overall effect more visual than novelistic, in that each is set alongside and in contrast with the others rather than there being any sense of development (reviewers frequently described The Vegetarian as a triptych, which seems wholly apt). From the metaphysical darkness of an untethered soul, through the scathing anger of a tortured political prisoner, to the tremblingly repressed, emotion- and colour-leached nightmares of a former factory girl and union activist, the novel presents a complex range of tone-pieces, none of which are in any way reflective, mournful, or accepting.

The other two options I'd toyed with, ‘Restitution’ and ‘Reparation,’ were equally bad, hastily and somewhat shamefacedly abandoned once the penny dropped and I realised that the book was about the impossibility of precisely such things. And besides, they were a bit too uncomfortably like the blocky, self-important titles given to (mostly male-authored) books which trumpet themselves as being about National Trauma. In a conscious attempt to shake off this marketing-speak, I went back to the text itself and tried to listen more carefully to what it was telling me.

I remembered that during the translation process, I had to hunt down as many synonyms as possible for ‘erase,’ a word which kept cropping up in the original, occasionally as a variant but more often as a straight repetition, something which Korean is far more tolerant of than English is. Of course, a true synonym—a pair of words where not only the meaning, but the precise range and degree of connotations, is identical—is pretty much non-existent, so I also had to throw off the lazy equivalence I allow myself when using English outside of translation, and interrogate the various nuances of obliterate, annul, expunge, efface, excise, before deciding which would be most appropriate where. Wary, by now, of allowing Han's restrained Korean to become bombastic in translation, I favoured the simpler options; ‘obliterate’ appears only once, and in connection with the genuinely total destruction that can be wrought by radioactive bombs, whereas the disarming innocuousness of ‘erase’ and the bureaucratic impersonality of ‘expunge’ felt more suited to repeated use, particularly in Chapter Three, which deals with publishing and censorship. Using the same word at different points in the translation also enabled me to remind the reader of certain incidents and suggest connections between them. For example, having described the faces of the murdered as being ‘expunged’ with white paint, when I later use the same word for the censoring of a play manuscript (fragments of whose performance—part Greek tragedy, part native-Korean shamanic exorcism—are also later described, in one of the novel's most powerful sections), the intention is both to remind the reader that it is more than mere words which are being erased, and to trigger the kind of contrast between paint and ink, white and black, which hopefully echoes the book's structural juxtapositions of contrasting tonalities. As well as visual and plastic art being a recurrent preoccupation (staged performance here, video art in The Vegetarian, life-casting and mural painting in earlier novels), Han's writing itself seems to me to possess a certain visual quality, which I'm still struggling to define. For some reason, whenever I translate her work, I find myself arrested by razor-sharp images which arise from the text without being directly described there. My own very occasional interpolations—“sad flames licking up against a smooth wall of glass”, the bullet hole that opens up “wide as a surprised eye”—aren't actually my own at all; the words might be, but the images themselves are so powerfully evoked by the Korean that I sometimes find myself searching the original text in vain, convinced that they were in there somewhere, as vividly explicit as they are in my head.

Something similar happened with a word, ‘abrasion,’ which appears neither in the original nor in my translation, yet which was echoing inside my head the whole time. Han Kang plays language with the kind of near-unbearable intensity which Jacqueline du Pré applied to the cello, exploring its sensory possibilities through a continual detailing of the minutely physical—a bead of sweat trickling down the nape of a neck, the rasp of even the softest fabric against skin—which builds to such a pitch that even the slightest physical contact, no matter how intentionally tender or gently performed, is felt as violence, as violation. This enables us, as readers, to glimpse something of the visceral disgust towards physicality (most notably their own) which wracks several of the book's traumatised characters; a gift of empathy that's difficult to describe as such, given that it's also a discomfiting, even frightening intimation of trauma. It got to the point where, reading a description of water or sweat trickling down the line of a throat, I couldn't help but imagine that throat being slit open, a knife tracing that same path.

Translating from Korean usually involves editing out references to ‘body’ which are redundant in English; whereas in English a character would simply ‘turn to the left’ or ‘lean against a wall,’ in Korean you turn or lean your body, someone bumps into your body rather than into you. This time, though, I chose to keep a few of these instances, to emphasise the body as something separate from the self (with the jarring effect on the English reader an ideal counterpart to the characters' attitudes towards this awkward, fleshly encumbrance which is also, somehow, themselves). Chapter Four, narrated by a political prisoner whose torture was intended to rob him of his humanity and reduce him to an animal state—“when this body writhes and contorts and the words spew from its lips”—was the obvious place to do this, emphasising the body as a disgusting, stinking lump of flesh. Equally important, though, was to convey the sense that physicality, embodied existence in the world, can be rapturously beautiful as well as violently brutal. It was as an attempt to introduce the complicated entanglement of these two types of vulnerability that I chose to have Dong-ho feel ‘lacerated’ by the thought of Jeong-mi's fingers turning the pages of his old exercise book. I also hoped to produce a similar effect to that of ‘expunge’ by using the word ‘graze’ to describe instances of both kinds:

Those snapshot moments, when it seemed we’d all performed the miracle of stepping outside the shell of our own selves, one person’s tender skin coming into grazed contact with another.

To the fact that someone’s lips merely grazing mine, their hand brushing my cheek, even so much as a casual gaze running up my legs in summer, was like being seared with a branding iron?

Though ‘Abrasions’ felt more like a subtitle somehow, I could sense that I was on the right track in my search for a title. The next potential solution came even more directly from the text—from a particular feature of the Korean language which this book's content, and Han's own lexical precision, brought to the fore. Korean has two main verbs for ‘remember,’ one of which is a compound of the noun ‘memory’ and the verb ‘to do’—remembering as active, willed, intentional. The second is altogether different. Its literal meaning is to ‘rise up’ or ‘(re)surface,’ and it can apply to anything that has been submerged or buried, like the bodies thrown into the reservoir immediately after the massacre, imperfectly weighted down. In this case, memory itself is the active agent, leaving the individual with little control over what or when they remember. Normally, the two versions will be fairly interchangeable, a way for the writer to maintain some syntactical variety, but in this case the obvious thematic connections meant I needed to pay attention to how I translated the second option—often more literally than I usually would, with memories and thoughts ‘surfacing’ or ‘rising up’ inside the characters, to give the sense of them being almost ambushed by the past. It was English's characteristic multiplicity, the fact that the majority of its words will have at least a second meaning floating somewhere beneath the surface, that made me think ‘Uprisings’ could be the perfect title; a pun on the Gwangju Uprising, and on all the subsequent uprisings, both literal and psychological, that pepper this novel. In the end, the publisher decided that it wasn't quite right, but I did manage to smuggle it in, in a slightly altered form, as one of the sub-headings in Chapter Five. These weren't in the original, and neither were the section breaks in the same chapter, one of the most slippery and confusing in the entire book. We decided to insert them into my translation to help the Anglophone reader (for whom, unless they happen to be familiar with Korean history, the various historical references will hold little meaning) orient themselves, though I hope this hasn't gone too far. The slippages in tense in this chapter are absolutely intended to leave the reader as disoriented its protagonist, and they also emphasise one of the most striking and important features of the book: that, despite taking an event from 1980 as its starting point, it is not a historical novel. The past is not presented as past—neither antecedent to, nor separate from, the present. Rather, the past is unfinished business, both for the nation and the individuals involved; it irrupts as repressed memories for the traumatised, whose lives have in no way ‘moved on,’ and the selfsame current of violence is shown to recur—an insight perhaps owing something to the Buddhist notion of samsara.

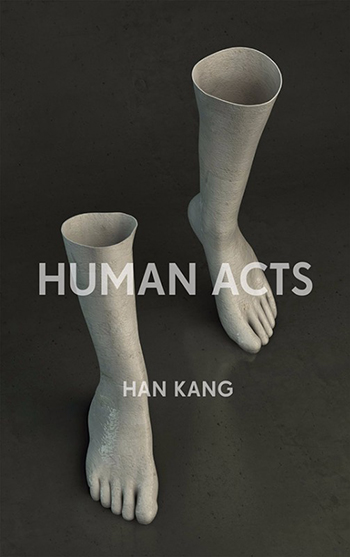

It was, then, a long and rather convoluted road that brought me to the eventual title: Human Acts, a phrase which to me embodied the neutrality, disorienting and even terrifying, inherent in the fact that these can be both tender and violent, brutal and sublime, committed by the same individuals. The one does not cancel the other out, does not atone for or even diminish it one iota. Han has described her own writing as an ongoing investigation into what it is to be human, or, as she puts it in this novel, “what we have to do to prevent humanity from being a certain thing.” Alongside the human element, I liked the theatrical second sense of ‘acts,’ both as a way of understanding the book's structure (if The Vegetarian was ‘a novel in three acts,’ this could just as easily be a novel in six, plus epilogue) and as a nod to the play which is staged in Chapter Three. It's not a perfect title. Perhaps, thinking of it only now as I write this, ‘The Boy Approaches’ could have been an option—the movement recalling a horizontal surfacing, perpetually present, perpetually stalled, carrying a faintly horror-movie shiver as well as the plangent evocation of everything the eponymous boy was approaching, that spring in 1980, before a combination of human acts unstitched him from his life.