These two East German writers shared an aversion to the creative shackles and main tenets of the official state policy of socialist realism, which demanded recognizable conflicts and positive heroes, and disavowed moral ambiguity in either characterization or narrativization. Indeed, Seghers wrote that:

I don’t think it can be right if, before setting to work, one first thinks about what kind of people one has to portray in order for them to be “typical”, and what paths they have to take in order to become a real “conflict”. That way one sees the idea first and then the reality; one first establishes the “typical” and then looks for the form it is supposed to express.

However, Seghers’ stature and seniority allowed her to flout these stuffy conventions with impunity, and to stand apart from the generation that had succeeded her, while Wolf, who consciously and closely drew inspiration from Seghers’ own narrative models, such as a concentration on “little men” protagonists, and non-linear narratological structures, was taken to task by the regime for her so-called literary “decadence”. This could well have been in the background when Wolf went on to note how: “Time flows differently for Anna Seghers than it does for me; it brings her different examples, shows her fates that are more finished and rounded off.”

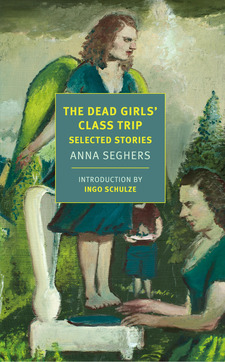

This new collection of stories from New York Review Books, following on from their recent translations of her acknowledged masterpieces Transit and The Seventh Cross, bears out the fuller veracity of Wolf’s observation, with each of its stories preoccupied in some fashion with the asynchrony of memory and the cataclysmic “rounding off” or abrupt termination of fates in the interwar period. In a selection that draws mainly from Seghers’ prolific output during the 1930s and wartime years (though notably thin on the ground when it comes to her GDR output), we encounter again and again characters whose lives, dreams, and aspirations were abruptly ripped open by the crosswinds of what Eric Hobsbawm called “the age of extremes”. Seghers died in 1983, seven years before the demise of the GDR, which she never openly contested. Approaching her work in 2023, we encounter a writer whose once-irreproachable status on both sides of the wall was itself subject to deterioration after the process of reunification began in 1989, until it became easier for some to not write of her at all than to confront what she may have represented (for instance until NYRB’s republication of Transit, it had languished out of print in English since the 1970s).

This change in fortunes came about partially due to revelations after 1990 of her silence—some would say complicity—as a member of the Writers’ Union during the trumped-up proceedings of “counter-revolutionary activity” brought against her friend, partisan comrade, and former publisher in Mexican exile, Walter Janka, at a show trial in 1956. Partially it was stylistic, for the type of avowedly committed, “partisanal” prose Seghers so finessed in her fiction and journalism from the 1930s onwards was ill-fitting to and somewhat altmodisch for the post-reunification Helmut Kohl years, which favoured popliteratur writers like Christian Kracht and the more obviously feminist work of Wolf and Ingeborg Bachmann.

So, The Dead Girls’ Class Trip, featuring new translations of canonical stories as well as several hitherto untranslated works, marks an opportunity to reconsider this significant German novelist. The picture that emerges is pleasantly ambivalent; a committed and distinctive voice caught in the historical and stylistic turbulence of the interwar years, steering a course between the Scylla of hard-line Zhdanovite caricature, with its “positive heroes” and conclusive acts of literary benediction, and the Charybdis of an open-ended impressionism, the prismatic sensorium and shifting boundaries we associate with modernists such as Katherine Mansfield.

Purgatorial Fictions and the Morphology of Escape

The first story in this collection, “Jens is Going to Die”, from 1925, begins, like Heinrich von Kleist’s “Earthquake in Chile”, by compressing everything we need to know about its protagonist into one dense fatberg of a sentence; Jens, we learn, will die. Then in reverse the whole reel of his life is run backwards from this terminal point, back to his parents’ first meeting, then to their courtship. This use of the flash-forward, evidenced here at the outset of Seghers’ career, would go on to become one of the main distinguishing traits of her fiction. The realism that initially prevails in the story is broken and refracted when the sickly young Jens awakens in his dark bedroom and confronts the strange metamorphoses of the night in which all cows are black:All the things seemed to be swelling, stretching. They could no longer bear to be standing there in their firm, clear outlines; they didn’t want to keep on being pots and chairs and shelves and books; they extended over their edges and pretended they had living faces and limbs.

This early moment of formal plasticity, a shifting, refracting sensorium in which every literary object exceeds its “clear outlines”—though sedimented in the phenomenological perspective of a scared child—is gradually forsaken in the stories that chronologically follow it throughout this collection; stories in which the outlines that surround and cut characters out from their historical and sociopolitical environments are traced in a progressively thicker and thicker impasto, with anti-fascist heroes eventually demarcated like apostles in a Giotto fresco by the haloes that girdle their heads. In the era of the Popular Front, the borders between interiority and exteriority, which seemed in danger of total interpenetration in Seghers’ early fictions, are once more sharply delineated along the faultlines of us and them: “friend” and “enemy”. In such instances, what makes for good politics arguably makes for bad literature.

In “Jens is Going to Die”, the sickly child develops a fever after straying into the chthonic depths of the nocturnal, adult world. The sick Jens is then skillfully othered by Seghers in his father’s perception, becoming displaced into the third-personal kingdom of the ill: “the mouth of his child, his one-time son” or “a thing that reminds you of something precious”. As in Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, Jens is slow to die. The story’s prismatic, shifting perspectives revolve around Jens’s sick bed—dramatizing throughout the when not if of his death. In this early fiction from Seghers we journey around, outside, and within Jens and his illness, attending as much to the metonymic traces it registers in the world as to the “interior world” of his illness (blood-stained sheets, the indifference of his friends, the increasingly routine way in which his parents relate to him). Illness comes to rob Jens of his youth before it takes his life—we feel it consume his élan vital. Yet as the years pass, this “slow death” is routinized, becoming a matter of waiting, of deferral, of endless protocols and procedures. It is here that perhaps the great theme of Seghers’ literary output is already apparent right at the outset of her career: the vagaries of time wasted, of time bided, of time lost; of purgatorial, unrecapturable days in pursuit of the unattainable or in flight from the inescapable.

In the longer family saga of the “The Zieglers” (1928), which builds upon the phenomenological vivacity of “Jens is Going to Die”, metaphors of containment, entrapment, and expulsion also abound. The kaleidoscopic quality of Seghers’ description deprives objects and the “objective commodity world” of Weimar Germany of its self-satisfied permanence or solidity, rendering all that is solid into air:

As he gazed around at it, the walls became warped; scraps of wallpaper had been torn off and pasted back on, no longer covering the triangles of mortar. The rug was frayed; cushions had burst and been sewn back up with big stitches. The heavy sofa resembled a large, half-eviscerated animal with its guts spilling out. There were just a few firm spots that still anchored the living room, a photograph, a mirror, a small golden vase. He had only to step down hard and everything would fall apart and he would be out in the open.

Meanwhile the social and objective worlds are shown to intermesh in inexplicable ways: torn duvets burst open of their own accord, exploding their feathers; the irascible father character erupts without provocation; blood spools mysteriously out from the mother; cold cuts and lumps of cake tumble humiliatingly from a care package piteously conferred on the impoverished Ziegler household by their neighbours. The interwar period and its manifold immiserations are depicted throughout marvellously, almost fantastically, as a forcefield of mysterious, violent eruptions waiting to happen.

In the years following the financial crash, the precariously employed patriarch of the Zieglers spies on the vagrants who congregate near the river, admiring the lackadaisical pace of their lives seemingly freed from the reifications and encumbrances of work. They “allowed their time to flow away in small, golden whorls of water”, just as a former acquaintance is enviously noted in the same story to have “measured time from one pub to the next”. The narrator also remarks of the drag of the days during the Depression, of how during the Christmas break “they all wished that time would move on; after all what could they do during this respite; it would be better if this grey, terrible time were to keep flowing along.”

This adagio tempo, fitting for what Seghers repeatedly called a “transitional era”, would gain its most lasting treatment in her magisterial novel Transit, written whilst she was in exile in Mexico in 1941–42, and recently adapted into a curious film by Christian Petzold. Indeed, many of the best stories in this collection read as preparatory treatments or calisthenics for Transit. This exilroman, which a friend recommended to me as perhaps “the most boring novel he’d ever read”, stands as perhaps the definitive post-war treatment of what one could call the morphology of escape. As the novel’s unnamed protagonist forms one loose, transactional attachment after another, in the hinterland of Marseille, where everyone claims to be soon moving on but somehow never leaves, his discourse with these equally forsaken acquaintances is gradually pared down to exchanging gossip about the necessary instruments for getting out and the means of obtaining them: the Safe Permit Pass and the Border Stamp, the Exit Visa, the Danger Visa, and the Transit Visa. These bureaucratic instruments form the novel’s ontology, both tantalizing and imprisoning with their promise of mobility. As per my friend’s remark, the fear of tedium indeed structures Transit, whose framing device contains the protagonist’s note of hesitation in even beginning to tell his ordeal to another new, temporary friend in Naples: “if only I weren’t afraid it was boring!” As he languishes in the Marseillesian dockside cafés and pizza parlours, bureaus and bed and breakfasts, indefinitely extending one Visa after another, he reflects on how, like so many of the other doomed protagonists of Seghers’ fiction, and of her interwar generation in general: “no visible harm has come to me so far except that the miserable state of the world happened to coincide with my youth.”

In the title story of this new collection, “The Dead Girls’ Class Trip”, the narrator (a clear author surrogate) plays with the dramatic irony of an extended reminiscence of a school trip in the 1910s, and the subsequent lives of the girls in this “dead class”; once again foregrounding the grim wastage and early expiration of lives in the interwar period. This exceptional story, which tellingly gains an additional distinction as the only one of Seghers’ fictions to have remotely approached the “autofictional”—drawing as it does directly upon the circumstances of her own biography—is by far the strongest in this collection. It begins with Seghers in exile in Mexico, where she remarks that “the refuge afforded by this country was too uncertain, too questionable to be called salvation or sanctuary”. In this desolate landscape far from Europe, the protagonist (worn out and dehydrated from walking in the mountains) is transported by the sound of a familiar name being called—“Netty!” (Seghers’ birth name, before she adopted her nom de plume)—through a cactus palisade, and back into the past. She then finds herself back in the company of her two best friends from school, Lena and Marianne, on a school trip. As is customary for Seghers, the dramatic irony foregrounds the two separate fates of these girls early on: Lena will eventually be dragged off by the Gestapo, her communist husband killed; while Marianne will become a collaborator married to a senior Nazi. The suggestion then, unlike in the later story “A Man Becomes a Nazi”, is of this childhood trip as a prelapsarian condition, an unrecapturable idyll perched on the precipice of disaster, of a “trip we took while there was still time”. This perhaps uncharacteristic note of a fatalism beyond those “blue remembered hills” is evident when the narrator writes of “Hitler’s rule and the start of a new war as a sort of severe natural phenomenon”. It is also there in the suggestion of the girl’s lost comradery: the agāpe of a more innocent time, in which they walked together arm in arm. Before they were riven by the political divides of the interwar period: “Marianne, Leni, and I, all three of us, had our arms intertwined in a unanimity that was part of the greater unity of all earthly beings under the sun.”

Perhaps the most interesting feature of this disquieting journey through the past is the equivocal way Seghers chooses to abruptly draw it to a close. A rapid mechanism suddenly ruptures the daydream of the older Seghers as, like a ripple dissolve from Hollywood’s Golden Age, the stairway of her past family home morphs into the steep Mexican hillside; the “banister turned and curved” becoming a “mighty picket-like fence of cacti”. Once back in the present day she returns to her desk and to one of her signature themes, this time in a more melancholic register—the occupation of empty, wasted time:

I now sensed an immeasurable river of time, as uncontrollable as the air. We had been accustomed, after all, since we were little, to do something with our time, to manage it, instead of humbly giving ourselves up to it. Suddenly I remembered the teacher’s assignment, to carefully describe our class trip, our outing. I would do the assignment first thing tomorrow, or maybe even tonight, once this weariness had passed.

The story, and perhaps literature in general, can thereby be understood as but one way of abstractly occupying the dead hours of life in exile; as a mere form of distraction. However, it could also be interpreted as a demonstration of Seghers’ theory of the literary Lichtpunkten, or spotlit detail amidst the murk and the darkness (an idea she drew out from her doctoral research into Rembrandt’s portraits of Jewish life). Which is to say that, by wresting agency back from the torpor and tedium of exilic life through her writing, Seghers models the capacity to shape her fate rather than “humbly” surrender herself to it or the torment of memory.

The Engineer of Human Souls: Popular Front and Wartime Stories

The Popular Front (Volksfront) era in interwar fiction is usually taken to have officially begun with A. A. Zhdanov’s famous speech to the Soviet Writers Congress in 1934, at which Maxim Gorky and Nikolai Bukharin also delivered canonical statements on the social function of literature. The precise origins of the term “socialist realism” are disputed, though it has often been credited to Stalin himself. As Zhdanov sonorously declared from the lectern in his presentation “Soviet Literature—The Richest in Ideas: The Most Advanced Literature”, arguing against the “decadence” of bourgeois modernism with its celebration of criminality and moral ambiguity, the “writer as the engineer of human souls” should instead be engaged in producing:

literature . . . impregnated with enthusiasm and the spirit of heroic deeds. It is optimistic, but not optimistic in accordance with any “inward,” animal instinct. It is optimistic in essence, because it is the literature of the rising class of the proletariat, the only progressive and advanced class . . . In addition to this, the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic portrayal should be combined with the ideological remolding and education of the toiling people in the spirit of socialism. This method in belles lettres and literary criticism is what we call the method of socialist realism.

Having left Germany, via Switzerland, for Parisian exile in 1933, Seghers went on to become intimately involved with the anti-fascist organizing of the Popular Front, helping to arrange the First International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture in 1935. As such, she was also closely connected to the often fractious and prolonged “method wars” on the left regarding the relation of literature to society and the role of the artist/novelist in the fight against fascism. One flashpoint in this struggle was the Expressionismus-Debatten between Bloch, Benjamin, Adorno, and Brecht on the one side, and Lukács on the other, pitting modernists (here notably associated with the Expressionist moment from the 1910s) against the revanchist Zhdanovite prescriptions for a “popular realism” coming from the USSR (where Lukács was then based). The texts produced in the smithy of this dispute, such as Lukács’s essays “Healthy or sick art?” and “Narrate or describe?”, would go on to serve as critical pillars of socialist realism as a dogma for many years to come. In her own intricate and knotty correspondence with Lukács in 1938–39, however, Seghers’ defence of modernism against the Lukácsian charges of “decadence” and “subjectivism” is noticeably mild, and their commonalities seem more evident than their differences. She rightly insists, however, on the historical mutability of “realism” as a category (citing the rapidity with which the alarming modernism of the impressionists began to congeal into a new classicism), and also pushes back to disaffiliate “decadence” from “fascism”, stating that the tacit authoritarianism of his critical line could endanger the full humanist expressivity and diversity of literature: “I am afraid we are being faced with an alternative where it is in no way a question of either-or, but in this case rather of combining the two, of a strong and diverse anti-fascist art, in which everyone who qualifies as an anti-fascist and writer can take part.”

Despite her avowed commitments to a “strong and diverse anti-fascist art”, however, a close examination of the Popular Front and wartime-era stories Seghers produced cannot but suggest a certain recontainment of the metaphorical phantasmagoria of her earlier fiction into a stricter objective realism, one for which Balzac or Tolstoy supplied the models. The stylistic jump cut from “The Zieglers” to the “Lord’s Prayer” (1934) in this collection is particularly stark, as we once more encounter the characters of the Ziegler family—this time on the flatbed of an armoured truck.

The title of “The Square” (1934) denotes the indelible outline left on the wall of a formerly communist household, where the portrait of Ernst Thälmann (the erstwhile leader of the Communist Party of Germany) once hung. Though the communist’s daughter, from whose perspective the story is narrated, is forced to comport herself to the dictates of Nazi socialization and begins to forget her father after his arrest and persecution, “the hole in the wall” of this square outline persists like a scar that will not ever fully heal; while also supplying the essentially optimistic image mandated by Zhdanov. Whereas in ‘The Zieglers” it is the presence of a photograph that alerts the young and urbane Ziegler to his father’s death (“His glance fell on the photograph above the sofa. He sat down at the table and looked up at it, puzzled and relieved, for he realized that, if his picture was hanging there in that spot, then his father, of whom he had been so afraid, must be dead. He took the cap off his head and shrugged”), here it is the absence that registers a metonymic trace in the world: “She looked around and seeing her mother’s old, dyed dress, she knew that her father was dead; she also thought about how he had died. She realized that her mother was a coward and wanted to deceive her child and that it would be useless to ask any questions.” Unlike the moral and political inscrutability of the young Ziegler, with his social aspirations, the moral and political affiliations of the communist’s daughter in “The Square” are left unmistakable in their sheer certitude throughout.

The epilogue to the “Best tales of Woynok, the Thief” (1938), with its elliptical affirmation of the contribution that “dreams, trivial songs, and chance impressions” can make to the psychic life of the individual, compresses the critical sentiments that elsewhere found expression in her correspondence with Lukács. In this story the collection takes a shift into the allegorical as a way of mediating the horrors of fascism, thematizing the recrudescent atavism of the fascist state as a sort of neo-Viking horde. Though arguably an anti-fascist parable, it is far from didactic in its resolution—as Woynok the thief, after first abandoning them, then returns to the company of Guschek and the thieves.

“Shelter”, a story about shelter and refuge from 1941, once more returns to the grim reality of the Heimatlosen. Here the signs of Zhdanovite hunger for heroes and caricatures begin to impair the presentation of the husband who forsakes his anti-fascist scruples to become a one-dimensional petit-bourgeois, whose desire for a quiet life hardens his heart to the child seeking shelter from the Gestapo. By this point the querulous, expansive literary modulations of “The Zieglers” seem to have been long forsaken—as one more luxury to be rationed in wartime.

“A Man Becomes a Nazi” (1943) begins plainly, and almost portentously, “there was once a German whose name was Fritz Mueller.” In a narratological ouroboros typical for Seghers, we begin in a Red Army courtroom and then dial back chronologically to his birth. From the outset any strictly psychoanalytic or pop-Freudian inciting incident for Fritz’s metamorphosis is dismissed, for “Mrs. Mueller raised the child like most of the other mothers . . . raised their children”, a statement that carries an ambivalent echo—and yet they too became Nazis. The seeds of resentment are nevertheless sown early on by Fritz’s father’s disenchantment, and the discrepancy between the pacifist liberal Weimar platitudes of the classroom and the heroic war myths propagated by his father’s generation. Unsurprisingly, young Fritz—the man who becomes the Nazi—is shown to be a mediocre intellect. An early incident of ultraviolence against a classmate is also not the canary in the coalmine we might expect, for it does not concretize into a pattern of violence. An effort is made by Seghers to suggest envy of his better-performing Jewish classmates, and the explanations procured are almost unbearable in their didactic simplicity: he resents the Jews because of a personal animosity against a local tailor (there is no suggestion of any structural basis for antisemitism). The school report is itself reported on, in the same documentary style as the rest of the story: all of it in a colourless grey-on-grey. In this fashion the story enacts the larger whodunnit, regarding the measure of culpability of the German people and state to fascism, in which Seghers and her communist and Popular Front comrades were so intimately engaged (no small part of their energies were oriented toward recuperating a different, enlightened, German identity).

For contemporary eyes, there is an artlessness to the way in which the general and the particular intermingle in this story, which is instructive for considering the formal constraints of the sclerotic state-sponsored socialist realism to which Seghers was apparently opposed. This results in doggerel such as: “the life he was embarking on was characterized by standing in line at the unemployment office and loitering about on the streets. This was the time in which every fourth man in the German capital was unemployed.” The incorporation of such statistics into the dry, documentary presentation of Fritz’s character, with their suggestion that whatever irreducible particularity there is to his biography it nevertheless ultimately partakes of a certain statical typicality, arguably works against the grain of the stories’ anti-fascist aspirations. They also seemingly belie Seghers’ own later declaration that I don’t think it can be right if, before setting to work, one first thinks about what kind of people one has to portray in order for them to be “typical”. Here every descriptive detail appears only by virtue of its illustrative significance, reducing the dimensionality of Fritz’s story from that of “The Zieglers” and transferring it into the paper-thin silhouettes that flutter out from party gazettes. This one-dimensionality is far more marked when compared to less mechanistic and shallow fictions also exploring “how a man becomes a Nazi”, such as, for instance, Klaus Mann’s Mephisto, Nabokov’s Despair, or Louis Malle and Patrick Modiano’s film Lacombe Lucien. These are accounts which do not shy from examining the noxious lure of fascism, the magnetism it effected upon the out-of-work, the unemployed, the vainglorious, the downtrodden, and other demographics who had little or nothing to gain from its dominion. When Seghers does approach this question, it is again only in the most cosmetic of terms, as the narrator remarks that “they all wore splendid boots; there wasn’t a tear or a spot on their brown shirts; there were drinks, and it didn’t cost anything.”

There is then an understandable fear the text makes legible of entering into the interior of the Nazi mind, nevertheless Seghers skillfully depicts Fritz’s rapid passage from the peripheries of the movement to its upper echelons, so that we swiftly encounter (in a moment of deft defamiliarization) “the SA Group leader Fritz Mueller” riding through the street firing indiscriminately. Fritz swiftly acquires seniority and progresses from the SA to the SS elite regiments. The entirety of peacetime Nazi rule, from 1933–39, then zips by in a few scanty paragraphs. Along the way he becomes desensitized to ultraviolence. The equivocity of the story’s early section, bracketing as it does the question of the truly determining variable in the nazification of a generation, is carelessly abandoned by its end, when Seghers writes of Mueller’s underlings that “the soldiers obeyed, for they had gone through the same schooling”. It ends in 1943 with the military lieutenant of the Red Army’s War Crimes Commission interrogating Mueller in the dock, and asking the question that would so often be asked during the process of “coming to terms with the past” (Vergangenheitsbewältigung): “Is it possible to comprehend that such a creature could have been born of a human mother?” It’s a puzzle that, arguably, this story does not come much closer to resolving.

“The End” (1944–45) dares to envisage an end to the war—exploring how a former camp inmate, Volpert, encounters his guard, a Mr. Zillich, as he navigates civilian life after the war. On meeting him, Volpert wondered “can this really be his wife? Is this really his garden? . . . was this really the same man?” On the run from persecution, Seghers shows us how Zillich fears the ruses he himself used to catch out and persecute communists and other Nazi undesirables. One of her typical Heimatlosen, he traipses, paranoid and pitiable, between short-term work contracts, continually ducking out the second he has no longer evaded detection. This results in a more daring exercise in moral anxiety than the stories that preceded it. His fate reproduces the shadow-life of those he preyed upon—resulting in an allegorical symmetry that is nevertheless too schematically insisted upon, somehow too diagrammatic. Like the Jews, communists, and other victims of Nazi persecution, we are led to believe, he too finds himself spurned: another one of Seghers’ in-between, purgatorial figures awaiting either damnation or salvation. Overall, this story embarks on a more concerted effort at the characterization of the enemy than “A Man Becomes”, especially in its depiction of the former camp guard’s total lack of remorse: “Zillich was glad when the Americans had passed them without incident. He was in no mood for trouble. He no longer wanted to stand up for something that had failed. He yearned only for peace and quiet.”

The exilic condition of flight, of the “transcendental homelessness” (transzendentalen Obdachlosigkeit), which the young Lukács established as the novel’s condition of possibility in his Theory of the Novel, is the common fate shared by all Seghers’ characters from this era. “Mail to the Promised Land” (1944–45) relates the story of the Greenbaums, a Jewish family that resettles in Paris. One of the Greenbaum brothers insists on the universality of the exilic condition, “whether you lived in Paris or in L., in America or in Vienna, you were living in exile. An exile God had imposed.” Old Levi relocates from Paris, where his family is intent on assimilating to the Promised Land of the young Israeli state. But “little by little he realises” that he was “still living on earth and caught up in all the discord of everyday life”. Back in Paris, the doctor’s son thoroughly assimilates, whilst Old Levi succumbs to illness, maintaining throughout their long-distance correspondence: “he was forcing himself to write as if thereby pushing aside the certainty of death.” Here again we find the thematic of literature and art as a means of forestalling the passage of time. After he dies, his son continues a pre-planned and backdated correspondence with his father. This results in a correspondence suffused with dramatic irony, one that conceals both of their true states: his frailty and disappointment with the Promised Land, and his son’s death. The dead son tries to establish a timeless correspondence, one unperturbed by the crosswinds of history, resulting in increasingly abstract letters that approach dreamscapes (“It seemed to the father that his son, who had always shied away from talking a lot, was only now, in writing these letters, discovering a previously hidden eloquence.”) Even when Paris falls to the Wehrmacht, in his letters the dead son speaks only of his work.

The final wartime story in the collection, “The Innocent Ones” (from 1945), adroitly and acerbically allegorizes the protestations of innocence made by those industrialists who aided and abetted the Nazi project. Suddenly everyone everywhere throughout the deposed fascist state is revealed to have actually been an anti-fascist—the true culprits seem nowhere to be found. Each and every industrialist, no matter their seniority, avows to have been answerable to someone more senior than them. In an irony thick as treacle Seghers has one of them state “Believe me, I never ceased in my efforts to destabilize that regime . . . But Hitler was as tough as leather.” Eventually the commission, intent on finding the culprits, tracks down Hitler himself—hiding in disguise in a cellar amongst some Jews.