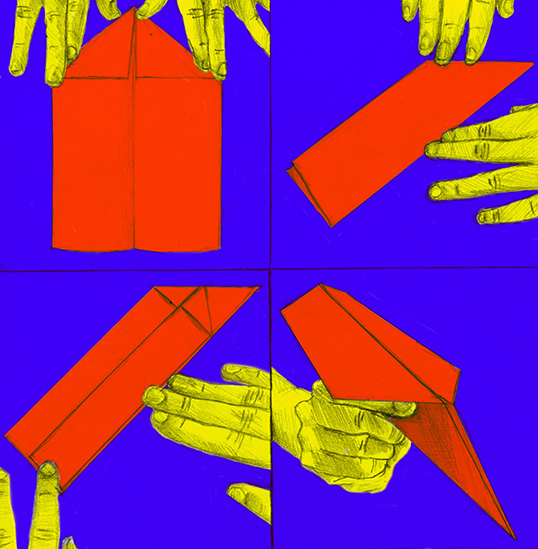

Now I folded the paper in half and pressed down on the crease with my palm, once, twice, three times. The last step was to fold the two flaps lengthwise to make the wings. Wings are the crux when you’re making a paper airplane. The weight of the airplane has to be centered, which requires the wings to be in balance, and then all you need is a flick of the wrist and it’s up and away. So you have to fold the wings just right, with sharp creases, to make it fly where you’re aiming it.

I took my nice new paper airplane to the open window of my daylight basement room and scanned the second-floor noraebang parlor across the alley, but she wasn’t there. Or at the convenience store on the ground floor below. I looked down the alley and she wasn’t there either, but the man in the cardigan sweater and the man in the Nike sneakers were coming up the alley. They went up to the noraebang, and less than ten minutes later she came up the alley.

Her shoes had four-inch heels. She always wore those shoes, wanting to look taller, I guess, but even the extra four inches left her short of five foot two. My wife also was just short of five foot two. I liked short women. And that was why I liked my wife. Maybe it’s a peculiarity I have about members of the opposite sex, but whenever I embrace a short woman I find myself thinking this is the woman for me. When the woman stopped in front of the convenience store for a smoke I let fly my paper airplane. It landed right in front of her—perfect. She gave me a what’s-up-with-this glance, tromped on my paper airplane, and up to the noraebang she went. I watched her singing with Cardigan and Nike in room four.

Two months ago I moved here from the apartment where I used to live with my wife. The first thing I did after unpacking was to go around dropping off my resume. But no one was hiring a forty-year-old man. wanted: workers under 40. Well, counting my age the Western way I was only thirty-nine, so I emended my resume accordingly, but it was no use. Even the places advertising for experienced help, every last one of them, said you had to be under forty. Telling myself every dog has his day, I dropped off my resume at one-hundred-plus places, thinking one of them has to bite, but I didn’t hear from a single one. Age forty had marked me forever as an old man. So I took to lying in bed and staring up at the ceiling like an old man awaiting death. And when I got tired of that I started looking up at the noraebang. And then one day I heard a tambourine and saw the woman singing there. Since then, come nighttime I’d watch the noraebang. And if I couldn’t see the woman I’d watch the convenience store.

The lights never went out in the convenience store, which bustled with Japanese tourists venturing out to the alleys from their hotels at the airport nearby in search of cup-ramyŏn. The convenience store was busiest during the day, the noraebang parlor at night. Broadly speaking, there were two types of noraebang patrons: the ones who sang for an hour or two and left, and the ones who paid for one of the women to sing and have fun with them. The first group arrived after dinner, did their singing, and went home, leaving at the latest before the buses and subways stopped running for the night. Cardigan and Nike were among the latter group of customers, those who had a woman join them. The woman was always there the times those two showed up. And of course there were nights when they didn’t come but she did. Some weeks she showed up three nights, some weeks four nights. But you could never tell which nights.

*

The woman left the noraebang with Cardigan; nine o’clock had come and gone. She followed him down the alley. I don’t know what possessed me, but I bolted from my daylight basement and hurried after her. Along with Cardigan she went into the hotel at the alley entry. I could see the airport beyond the sign for the hotel. From my hangout near the hotel I watched the airplanes taking off.

Thirty minutes later the woman emerged from the hotel. She looked around and went back up the alley. She was listing to the left as if someone above had attached a string to her right shoulder and was pulling on it. I tried walking that way myself. I noticed her scent, and that scent made me feel I liked her a little more.

The woman went back up to the noraebang and I went back down to my daylight basement. A short time later she emerged from the noraebang with Nike. Her eyes met mine and she turned away. The woman must be interested in me, I thought, judging from the way she avoided my gaze whenever we made eye contact. But who would want to cozy up to a man who made paper airplanes? Instead of going down the alley Nike checked out the surroundings from in front of the convenience store, then brought the woman inside the entrance to my building. Her legs and his were visible through the crack of the door to my place. He pushed her into a corner on the landing and pulled down his pants. His butt came into view, bright as the moon. Leaning back against the wall, she took him in, and once again our eyes met. I pulled the door shut, and once the pounding of my heart had eased I grabbed the broom and threw it at the rat under my bed. It scurried off to the corner. Last night the rat was gnawing at food scraps outside my window when the woman tossed a cigarette butt in its direction. The spooked rat took cover in my room.

“Wow, paper airplanes for wallpaper!” The woman had flung open my door without knocking and seen the paper airplanes littering my room. I looked out at the steps but Nike was no longer there. And without so much as a may-I-come-in the woman entered my room and looked around. The room was not quite 10 p’yŏng. From the doorway you had the kitchen to the left and the window to the right. Beside the window was my dining table, which I’d moved from the kitchen so I could watch the woman. Behind the table was my bed, beneath which I’d stacked reams of paper I’d brought home from the paper manufacturing company I used to work for—everything from printing paper to notepads, wrapping paper, paperboard, drawing paper, and A4.

“You can see this place plain as day from the noraebang. When I’m singing I always see things flying around here, and now I know what they are. Just think, a man who makes paper airplanes—wow! And you made them all yourself?” she asked wide-eyed.

“Well, what else can I do in this gloomy little space?”

“Can I try?” she said with a smirk, and then she bent over and felt the airplanes. Whish whish went the paper. The woman’s lipstick was smeared and her mascara was smudged. There was a snot-like stain on the hem of her skirt—Nike’s semen. She noticed me noticing it, tore one of the airplanes in half, and wiped at it. A sharp corner caught on her skirt and pulled out a thread. She made a face.

“It’s not like I wanted my life to play out like this,” said the woman. “You see, I had a dream.”

“A dream?”

Just then an airplane came into sight, climbing above the noraebang building. The roar rattled the window and set the paper airplanes trembling. The TV turned to static and my room filled with the hiss and the rattling.

*

When the airplane had passed overhead she went up on her toes and pulled me toward her. I could feel her chest below mine. Her warm flesh made me hot. With one hand I drew her close and with the other I went inside her blouse and felt her. Her breasts were as small and soft as my wife’s. And then I got busy—I removed her bra and lowered her skirt. The headlights from a passing car reflected from her body. There was a bloom of light on her neck, the next moment on her mouth, and then on her hand. A bloom of light on her navel, and then there below. Red sparks on her body. The car passed by and the blossoms disappeared.

I sucked on her breasts, seeking those vanished blossoms. A blossom appeared on one breast and then the other. Blossoms redder than sparks. I swept up the short woman and laid her down on my bed. Kneeling at the foot of the bed I crawled up her like an earthworm. I crawled and caressed, pouring out my heart, and by the time I reached her chest she was melting. Seeing the blossoms on her chest, I slowly entered her.

“Is it all right?” I asked her as I used to ask my wife.

“It’s great!”

That got my rear end moving faster. Her fingernails dug into my bottom and the next moment I shot. Her legs coiled about my waist squeezed tight.

“My dream was to be Korea’s Ishida Ayumi. You know, the ‘Blue Light Yokohama’ singer. I liked her so much I took Ayumi as my stage name.”

She uncoiled her legs, rose, and lit a cigarette. A white wisp rose from the end. She drew quickly then bent down and sent the smoke inside my mouth. I smelled her in that smoke. It was a good smell and I drank it in. I was getting to like her.

Giving me another mouthful of smoke, she said, “I started out singing at this dive where they called me The Dwarf instead of Ayumi. I’m short all right but the guys loved me. They were always hanging around telling me they’d make my dream come true. So I thought okay and I slept with them. But once they’d spent the night with me they were gone. And that’s how I rolled into this out-of-the way noraebang place . . . So what was your dream?”

“My dream was to be a pilot.” I used the English word. “This is the place I lived in when I was a kid. When I saw the airplanes taking off I wanted to fly one of them to Hokkaido—that’s where my mother was, see? But my dream was shattered the day my mother returned—she came back in an urn. I sprinkled her ashes, I made one last paper airplane, and my dream of becoming a pilot folded up along with the paper for that airplane.”

I made my first paper airplane the day my mother left for Hokkaido. After school I would bury myself here hoping only for her return while I made paper airplanes and sent them flying. A week went by, then a month, then a second month, but she didn’t return. Still, I made and launched my paper airplanes. It must have taken a year for them to reach her, because that’s when I got the news—she had died. After scattering her ashes I stopped making paper airplanes.

I started up again after my wife dumped me for the man who lived across the street. The man was two years younger than me and we were friendly enough that we used to call each other Brother. My wife and I felt sorry he had to eat all by himself and we always invited him over for a meal, and before I knew it they’d hit it off. I told myself No it couldn’t be, and at night I waited for her. My ears perked up whenever I heard steps outside the window, but morning would arrive and still no sight of her. I went AWOL from the paper manufacturing company and made paper airplanes hoping only for her return. Two months went by but she didn’t show up. I wanted to fold up my wifeless existence once and for all. But for the life of me I couldn’t. Instead, I loaded my belongings into my truck and moved back here where I’d lived with my mother before she went to Hokkaido.

*

The following day the woman turned up at my place with her belongings in a grocery cart. The cart was a jumble of clothing, shoes, cheap cosmetics, a battered roller bag, a purse, and a tambourine. And there was a potted plant with round leaves and a travel guide to Hokkaido. The guide had dog-eared corners and ripped pages—she must have read through it a thousand times. One at a time she handed me the items from the cart. I lined up the cheap cosmetics and the tambourine on top of the TV, then set the plant near the window where it would catch the sun and gave it some water. Her shoes went into the shoe cabinet, the travel book on the bed. I put the roller bag in the closet. Her clothing occupied the space in the closet where my wife’s clothing used to be, before I moved them to the back and hung my own clothes over them. I had discarded all my wife’s belongings, except for her clothing, vaguely expecting she’d return someday. But once I’d moved back here I realized she wasn’t coming back. Once gone, time doesn’t return.

Now that the woman’s belongings were here, my place was full up. More than anything I liked the woman’s scent. Something about it reminded me of my wife’s scent. I closed my eyes and through my nose drank deeply of that scent. I felt just as if my wife was next to me and I smiled, and the woman took my hand and led me to the bed.

“You must be thinking of someone to be smiling like that? I’m not going to guess who it is, but let’s stop thinking and do some looking instead. How about a tour of Hokkaido?”

I lay down on my tummy and she opened the travel guide to a snow-covered mountain soaring high and mysterious into the sky. A pale moon hung above the mountain, whose lower reaches were clustered with traditional Japanese dwellings, only the snow-covered roofs visible. The woman flipped to the next page, to a photo of a couple walking hand in hand in the snow, a timeless scene. Two by two their footprints trailed behind them, soon to be buried by the falling snow. And with a swish overhead the wind would pick up and the next moment the couple would no longer be seen. Crows perched on utility poles, a train dashing through the snow, Hakodate at night seen through the falling snow, an endless, snowy, gently rolling expanse of white birches, lovers kissing in the snow—these Hokkaido snow scenes left me feeling lonesome like when my wife had left me.

I closed the travel guide and told the woman I felt lonesome. She produced a cigarette, lit up and took a few puffs, and the next thing I knew the smoke was inside my mouth. Drawing it deep in my lungs made some of the lonesomeness go away. But it came back when I breathed out. I told the woman I was feeling lonesome again, and she undressed and took me in her arms. “Then come. Come inside me and your lonesomeness will go away.” So I went inside her. Her body was deep and warm, unlike my wife’s cold body. The fact is, I wasn’t able to make love to my wife more than once or twice a month. By the time I got home from trucking paper all over the country it was two in the morning. I’d rush through a shower and go inside my wife, but before I knew it I’d be conked out. When this developed into a routine my wife no longer welcomed me. But the woman welcomed me with all her being. I got to thinking that this woman, and not my wife, was the woman for me.

“Where do you think that plane’s going?” the woman asked me after I’d shot. She was watching an airplane rising above the noraebang building.

“To Hokkaido.”

“Really?”

“I’m pretty sure. That’s where my mother went on one of those planes.”

She looked out the window at the airplane until it had vanished into the darkness and then she got dressed. Burying her face in my chest, she asked what I wanted to eat.

“Anything is fine.”

“But I don’t know how to cook anything.”

“Then how about fried rice with veggies and meat?” I would have chosen something else except I was used to fried rice, which my wife made for me on weekends. The woman made a trip to the convenience store and came back with carrots, broccoli, and pork. She chopped the vegetables into manageable chunks and dipped the meat in boiling water. After slicing the pork she put it in the frypan along with the vegetables and some leftover rice, added soy-sauce and corn syrup, and began cooking. Thirty minutes later it was ready. The woman transferred the meal to my wife’s favorite serving dish and set it on the table. The woman and I sat across from each other as we ate, the meal reminding me of my wife, but I didn’t let on. It tasted better than the fried rice with meat and vegetables that my wife used to make.

Afterwards I took the woman in my arms again. That was all we did in my tomb-like daylight basement room. The latest hits playing in the noraebang, the Japanese tourists going in and out of the convenience store, headlights from the cars passing through the alley—I was heedless of it all as I went inside the woman. Further and further I went, but there was no end to the depths of this woman. Still I wanted to reach that end, and on I went, sharp and poised. At the climax I cried out. I felt a surge of rapture so deep I could have died without a care. Rapture I’d never experienced with my wife, a feeling that I’d arrived at an extreme of pleasure I’d never been to before. Unable to forget that rapture, I went inside the woman again the next day. Along with the rapture I sampled her lonesome affection, and through that affection I grew to like her a bit more. In this way a dream-like week passed. For me that week could not have been better.

*

A week later the woman went back to work at the noraebang and I went to the airport and sat in the terminal and watched the airplanes take off. Was there any place better for killing time than an airport? Watching airplanes dissipated my boredom and for some reason made me giddy. Fantasizing about plane rides to cities I’d never visited made me feel I’d actually been to those places. At night the terminal thronged with Japanese tourists. I greeted them with a konbanwa or two, an expression my mother had taught me. Expressionless, the Japanese tourists responded with konbanwa.

I made a circuit of the terminal then returned to my daylight basement. It looked gloomier without the woman. I folded paper while I waited for her. There was good air circulation and the paper was at the service of my fingertips. Paper folded well only when the air was circulating. Otherwise humidity got to it and it ripped easily. As I folded paper I wondered where my wife was living. After she’d left I’d gone as far as the neighbor guy’s home village looking for her, but she wasn’t there. She’d run off with him somewhere I wouldn’t be able to find her.

I was still thinking about my wife when the woman returned. “Who’s on your mind that you’re so lost in thought?” she asked me. I told the woman it was my dead mother. I didn’t want to tell her about a wife I would most likely never see again. The woman found some citrus soda in the fridge, drank, and perched on the bed.

“I’m going to Hokkaido.”

“Hokkaido?” My voice went up an octave. “It’s so far away—what for?”

“I’m tired of just looking at the photos. I want to see the snow with my own eyes. I want to touch it, taste it, feel it. I want to walk through the endless snow. I want to sing while I’m walking through the snow, I want to sing ‘Blue Light Hokkaido.’”

“‘Blue Light Hokkaido’?”

“It’s my version of Ishida Ayumi’s ‘Blue Light Yokohama.’”

“Then let me go with you. I always wanted to go there myself—my mother used to live there. Hakodate, Otaru, Sapporo, Noboribetsu, wherever. I know some Japanese too—for ‘Hello’ you can say ohaiyo in the morning, konichiwa in the afternoon, and konbanwa in the evening. And for ‘delicious’ you say oishi. That’s all you need if you want to talk with the Japanese. So I can tag along and be your guide.”

The woman smirked and lit a cigarette. “I don’t need a guide. I’ve got this book. The first place I want to go is Hakodate. I fell in love with it the first time I saw the photos. The harbor at night . . . my god, what a sight. I’m going to do it up right and go everyplace you can see in the book. I’ll probably need the whole winter.”

“That long?” I said, dejected.

She nodded yes then talked about the Hokkaido scenery, the cities, and the snow. She also talked about chewy ramyŏn, and then her words were no longer registering. The more she talked, the more despondent I felt. Finally I interrupted: When was she returning?

“We’ll see, once I get there. I don’t know what’s happening tomorrow, so who can say what’ll happen then? If I’m lucky enough to meet a nice man like you, then who knows, winter could stretch into spring.”

And then she said she was departing the following week. So soon. I was distraught. I couldn’t just let her go. I liked her. No matter what, I had to hold on to her. If she left, I’d have nothing. I took her cigarette and had a puff. That had a calming effect, so I took another drag and then I tossed a paper airplane her way.

“You don’t want to stay with me?”

She obstinately shook her head. I thought she had come here with her cartful of belongings because she liked me. Wrong. I was a brief stopover, that’s all. She crumpled the paper airplane, backed herself onto the bed, turned off the light, and sank back against the wall. The headlights of a car that had stopped at the convenience store lit up her face. She grimaced and turned away. Soon the car went off and the room fell into darkness. And quiet—no airplanes could be heard.

After she fell asleep I ripped the pages from the guidebook and made paper airplanes out of them. Don’t let her leave for Hokkaido, I prayed, let her live with me instead. I don’t need my wife any more. All I want is the woman—her and a fresh start, here in my daylight basement. Embedding the paper with these ardent wishes, I folded like never before. Into the paper went the people and places in the alley and the wind that swirled through it, and the airplanes taking off above the noraebang building. And the latest hits playing in the noraebang and the young clerk nodding off in the convenience store.

After I’d made paper airplanes out of the guidebook pages I started making airplanes out of the woman’s clothes, any article of clothing I could lay my hands on, and after that the plant next to the window. What next? I spotted the rat. I thought it had left, but there it was, still holed up beneath my bed. I stuck my head under the bed and whacked it with the broom handle. There. It had been gnawing on my paper and its belly was bulging out. I laid it on the floor, pushed down on its belly, and the paper oozed out of its mouth like eggs from a frog. I wiped up the paper, then spread-eagled the rat and folded it the way I folded paper to make an airplane.

*

By now paper airplanes practically covered the floor. A breeze came through the window of my daylight basement and the paper airplanes on the table took off. They flew four, eight, or maybe twelve inches before landing on top of the ones on the floor. One by one I retrieved them and sent them flying out the window. Passing cars gave them a lift and then they came back to earth, some crushed beneath car wheels and others flying through the open door of the convenience store. “Welcome,” said the inattentive clerk, mistaking one of the paper airplanes for a customer. He looked in turn at the airplane and me, then nodded off. Other airplanes flew in and each time he rose like an automaton and mumbled a greeting.

I brought in the woman’s cart to load it with paper airplanes. Her blouse that I’d made into an airplane unfolded like toilet paper coming off a roll and returned to its original shape. I tossed aside the airplanes I’d made from her clothing and began loading the paper ones. As I was loading the ones from beneath the bed the woman returned.

“I got my ticket to Hokkaido!” Holding it in her hand, she swirled in a circle then took her tambourine from on top of the television and began singing “Blue Light Yokohama”:

How lovely the lights on the streets of Yokohama

The blue lights of Yokohama

I’m so happy with you

In Yokohama as always we speak of love . . .

The woman had a good voice; it was more lilting than Ishida Ayumi’s. She ended the song nicely, replacing the final “Yokohama” with “Hokkaido.”

“I don’t need the guidebook, you know. As long as I have this ticket. Anyway, it’s getting time to say goodbye to this daylight basement. And to you.”

I felt a lump in my throat when I heard “goodbye.” I grabbed a bottle of citrus soda from the fridge and gulped it. It went down the wrong way and I started choking. The woman snatched the bottle from me and drank.

“Why are you putting all those paper airplanes in the cart?”

“I’m tossing them.”

“Where?”

“Into the Han.”

“You’re tossing them in the river?”

The woman placed her ticket on the table and said she would go with me and began changing her clothes, her back to me. I sneaked a look at her ticket: she was going to Hokkaido all right, departing at 9:50 in the evening the day after tomorrow. I pocketed the ticket. Without it she wouldn’t be able to leave—and I wouldn’t have to plead with her to stay.

I carried the cart out and lugged it up the steps. In no time she came out, wearing comfortable clothing, unaware her ticket wasn’t there. We started off down the alley, me pushing the cart. We passed the motel, turned left, and there in front of us was the airport. Japanese flight attendants were exiting the terminal with their roller bags. “Konbanwa,” I said, waving to them. “Konbanwa,” they replied, expressionless. Past them we went and in ten minutes we arrived at the river.

On the nearby bridge were people in warm-up suits walking briskly. Closer by were people flying kites or fishing. We headed for a quiet spot beyond the anglers. There was a metallic screech and one of the back wheels of the cart came off. I stopped and had a look beneath the bridge. The river streamed by, dark and deep. I took a paper airplane from the cart and lofted it. Riding the wind, it came to rest on the water. It was joined by more and more of them and when I had launched all the airplanes in the cart the moon rose far down the river. The paper airplanes floated toward the moon but were water-sodden before they could reach it. The sodden airplanes brought to mind crows perched on utility poles, a train dashing through the snow, lovers kissing in the snow, Hakodate at night seen through the falling snow, an endless, snowy, gently rolling expanse of white birches—scenes overlapping with one another in the gentle rocking of the current. I took the plane ticket and threw it into the air.

“Are you crazy—that’s my ticket to Hokkaido. What do you think you’re doing!”

The ticket rose into the air but lacking wings it landed on the bridge. Pushing me aside, the woman ran and fetched the ticket and stuck it in her bra. I followed and put my arms around her.

“Please don’t go.”

“You don’t want me to go?” She twisted around and pushed me away.

“I love you.”

“Love? Is there any love left in this world? All the men who’ve slept with me are gone.” The woman was mocking me.

“I won’t leave you.”

“What a joke. You’ll leave me all right, someday. Love is gone, it doesn’t exist.” And then she kicked me in the shin and ran off. I rushed after her, clutching my shin with one hand and pushing the cart with the other. The people coming toward me were startled by the scraping of the cart and made way for me. The woman went into the terminal. I followed her inside with the cart. The woman went past a coffee shop and a pharmacy and snaked among a group of Japanese tourists with roller bags. The tourists stood aside, allowing me to cut diagonally through them and continue after her. She exited the terminal and crossed the approach lanes. I followed her across and then down the sidewalk on the other side. The people heading toward me broke apart to avoid the cart. At the motel the woman turned up the alley.

I left the cart at the top of the steps and went down to the daylight basement. The woman was lying down, facing the wall. She had her clothes on, probably afraid I’d try to snatch her plane ticket again. I didn’t sleep but merely watched her back; it was as flat as the airport runway.

*

The next evening the woman came home with her hair cut short and started packing her roller bag. I’d decided to make coq au vin for her and I began chopping the chicken I’d bought at the convenience store. I cut it in half, then cut each half into quarters. I put the meat in a pan and added cheap wine, which dribbled down over the chicken, turning the pink meat red. Then I cubed potato and pumpkin, mixed it in nice and evenly with the meat, and set the pan on one of the gas burners.

As the chicken was cooking, the woman’s items disappeared one by one into her roller bag and the room began to look like a mouth with teeth missing. The woman put paper airplanes in the empty spots, but that only made the spots barer. I took glasses and forks from the drawers and set the table, then added plates, turned off the lights, and lit candles. And just like that my dingy room took on some atmosphere. I’d bought the candles at the convenience store for our last night together. After thirty minutes of simmering I put the chicken in a serving dish and placed it on the table.

“The last supper and just for me?” said the woman as she sat. “Why thank you! What do you call this, anyway?”

“Coq au vin. Chicken cooked in wine. My wife loved it.”

“Your wife?” The woman looked at me in amazement.

“Yes, my wife. She ran off with a neighbor guy. She ditched me. So I came here. My mother ditched me too, just like my wife. Women don’t stay with me very long, they always leave. And now you’re leaving too.”

I took a bottle of citrus soda from the fridge and filled her glass and then mine. She clinked her glass to mine, took a sip, then set it down. She speared chicken with her fork and ate. With her paper napkin she dabbed at the juice on her lips. I focused on my soda and only poked at the chicken. Picking out the bones, the woman finished every last chunk of her coq au vin. I picked her up and set her flat on her back on the bed. She put her arms around my neck and drew me close.

“Let’s do it one last time.”

Her voice was coquettish, no tinge of sadness or lonesomeness. But I felt the lonesomeness I’d felt when my wife left, and I pulled her to me. Sliding a hand into her bra, I felt for the plane ticket. It wasn’t there, or in her panties either. Impatiently I undressed her, then flipped her over to see if she’d slid the ticket inside the back of her shirt. Nope. Where the devil could it be? I looked between the sheets but not a shred of paper did I find. She’d tucked away her ticket to Hokkaido in a place where I wouldn’t find it. And in that case . . . in that case . . . Looking at her back, as flat as the runway I’d seen the previous night, I made up my mind.

I looked at her and said, “I’m going to make you into an airplane.”

The “Blue Light Hokkaido” she’d been humming came to a halt and she gazed at me vacantly.

“You are?” she giggled. Just then the airplane for Hokkaido soared past the noraebang building and the next moment her giggling was lost in the roar of the engines. The window shuddered and then so did the woman.

“So now I’m foldable too? But I’m not made of paper.”

“Doesn’t matter. I’ve made everything in this room into airplanes—paper, clothing, plants, even that rat. I can make you into an airplane too.”

With my left hand I pressed down on her thighs and with my right hand on her back I brought her up a little at a time until she was perpendicular at the waist. She turned her head toward me. “You want to do it like this?” she said. “What a weird position!” I said, “No one else can do it like this,” then brought her down toward her outstretched legs until her back was arching like a bow and her squashed breasts were bulging out at the sides.

“You’re going to be an airplane. I’ll make you into an airplane and send you all the way to Hokkaido.”

I got up on the bed and trampled on her back. There were cracking sounds and then she went awk and there was no more resistance from her back. She looked just like a sheet of paper folded in half. Next I pushed her shoulders toward each other, then I folded her legs at the knee. There were creaking sounds, one for each of my folding motions. By now I felt I was folding paper rather than a woman. Next the wings. I pulled her arms away from her body and out came the ticket. No need for it now, so I picked it up and put it back where it came from—it was part of the airplane. Wings are the crux when you’re making a paper airplane. The weight of the airplane has to be centered, which requires the wings to be in balance, and then all you need is a flick of the wrist and it’s up and away. So you have to fold the wings just right, with sharp creases, to make it fly where you’re aiming it. And so I bent her arms into position.

Now on the bed there lay an airplane rather than a woman. An airplane made from the woman. The most beautiful airplane I’d ever made. Time to send her off to Hokkaido. I set her in my palms. She felt so light it was like she didn’t weigh anything. Suddenly I missed her. I set her on the bed and took a sniff. Her scent was gone. I pulled her close and felt her. The strongest lust I’d ever felt came over me. I wanted her. But how could I have a woman who was now an airplane? I had to be an airplane myself, it was the only way. I had to be an airplane and ride the woman, ride the wind on her back.

Watching the woman who was an airplane, I took off my clothes. Last off were my socks, and then I folded my arms across my chest. I pulled my shoulders in toward each other as much as I could, folding myself in the same order I’d folded her. Folding my legs at the knee, I pulled my arms away from my chest to make the wings. And then I extended my wings so I could fly to her. But they didn’t move. No matter how I wiggled and squirmed, they wouldn’t budge. I waited for the wind. When would it come?