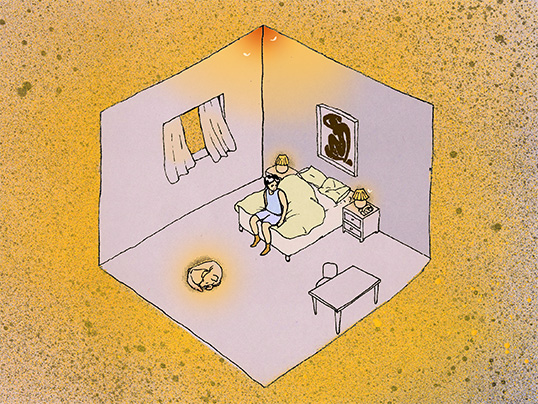

I was told this story by a very pretty young woman—whose face made me think of a turn-of-the-century French cabaret dancer—one dawn in autumn at the riverside hotel of a city in the interior. On this occasion, she told me that she could never forget a particular play performed by two women. One played a dog, the other a lonely woman who lived with her dog. The two actresses toured, telling the story of these two women. When they woke in the morning, each in her own hotel room—the women, not the actresses, if we can make that distinction—they always rested their gazes on a blank wall, with nothing of the past imprinted on it, like a play script seen for the first time in a dramatic reading, as-yet uncolored by the characters’ thoughts and fears. The blank wall only solidified their acceptance of nothingness. And waking in a hotel room was always a surprise, just as the walls were always blank. On restless nights, the kind that can turn blank walls into dragons with a mere candle flame, the actresses would get up in a desperate search for the light switch. Getting up always brought new adventures, too: they wouldn’t know the furniture layout and naturally accidents happen. But nothing serious, not like the seriousness of searching for the unknown. Everything was also exhausting: long streets where the eyes could recognize only what was green, an exhaustion of green; long conversations with municipal employees responsible for promoting the play, an exhaustion of the obvious; the exhaustion of committing each space and each image of every new place to memory—the room number, the location of the hotel’s breakfast room. They tired of needing to learn and absorb things that would mean nothing once they left that place for another; tired of eating, even, of needing to eat in the presence of people they didn’t know; tired of saying good morning to those strangers; tired of performing the piece for those strangers; tired of only ever meeting strangers; tired also of being strangers themselves. This exhaustion, which seeped into everything, had even taken over their ages. The ages they had yet to reach were tired of them both. The love they still lacked had tired of hoping in vain for them to find it. Besides, they sensed that, for single women, love was exhausting and, anyway, would remain absent with age.

The one who played the dog was prettier, and also had to be so: her role required nudity, and vanity had not gotten tired of her yet. Because of this, between the two of them, the one who played the dog was the one who didn’t always sleep alone. The poor men of the interior; they didn’t know that they might be to blame, the ones who always dreamed of one day sleeping with an actress, any actress. But the actress who played the dog made demands. It took more than wilted flowers. It took, though this didn’t need to be followed to the letter, the promise of someday coming to see her in the capital, to see her playing other roles, where she was more than just a dog. Not that she didn’t like playing a dog. She loved it. But people in these places wouldn't understand that. They didn’t know how to judge a play and this one was practically unclassifiable even for those who knew the classifications. The play wasn’t a comedy, nor was it a tragedy. It was almost a drama; it was almost nothing. Almost nothing, because people neither laughed nor suffered. Nor did it serve as a mirror. It didn’t even reflect those poor people who had never properly looked in a mirror. It was a drama very specifically for those two women. It didn’t draw laughter. And the suffering it contained was painless because those who attended had already made an unconscious pact among themselves: that they would never let a play make them suffer. That could perhaps happen in the cinema, but not in the theatre. Never in the theatre. The people chatted during the saddest part of the play. They wanted to escape what they were seeing and hearing, to escape that calamity. They wanted to leave because the misery was something that belonged only to the two women. So this was more or less what always happened—the women performed the piece for themselves. They never lacked for spectators, though: in those cities of the interior there was nothing better to do. To attend a play was still, at least, something different. Every day, in the hotel room, at the end of the show, the two actresses, separately, remembered that they had done the play for themselves, but, though they knew this, it didn’t make any difference.

On one of those days when desire was confused with need, the actress who played the lonely woman woke no longer wanting to play the lonely woman who, in fact, she was: she had gotten it into her head to play the dog from then on. I don’t know if it was because of envy of the other’s nudity when she played the dog; I don’t know if it was because she didn’t want to play the lonely-woman role anymore—playing herself; I don’t know if it was because she also wanted to have someone to sleep with some night or other; or because she didn’t want to die onstage every day in the final act. The truth is that it came to her. The girl who played the dog summed up the issue by saying, We can’t. She had sowed chaos. Tours to multiple cities had yet to be completed. The two practically stopped speaking to each other. All these years traveling with the play—eight in all—had already put them through every type of relationship: they’d been best friends; they’d debated in detail each phrase of the text they performed; they’d paradoxically dismissed the piece’s director, because they thought it was no longer his—and also, I might say, though they didn’t, both had had a torrid romance with him, a man of dubious marital status; they had opted to sleep in separate bedrooms since they could tell that things went better that way. In short, a variety of things had come to pass in these eight years, but nothing even came close to the astonishing idea of the lonely-woman actress wanting to play the dog. She didn’t even know how to play the dog, but wanted to test the other actress: could the other actress competently play the role that, until now, had been played by her?

At first, the actress who was now playing the lonely-woman role thought it would be easy. She had already, while a dog, played opposite the lonely woman for so long that she knew all of that part’s gilded speeches, onstage movements, intentions. But for that dog that used to be her to take the role of the lonely woman who looked at her and saw a dog was something she really wasn’t prepared for. This was not the worst, though. The most tragic—tragic in all senses—was dying. She had never died onstage. And she always knew, in her capacity as a dog, that the other actress, while playing the lonely woman over these eight years of touring the piece, never died truly as she should have died. And how was it that she should have died? This was something else she didn’t know, but now she had to figure it out and this was what tormented her. She must have been trained to die, and yet forgotten. She lived learning to live, at least, not realizing that death, one day, would be an occupation, or, sooner yet, a preoccupation in her life. They started rehearsals. The actress who now played the dog was alone in a state of excitement. She arrived punctually for rehearsal with one of those dresses she used for these occasions and had even telephoned the director, who soon showed up to orient them both with their new stage directions. By the time the other actress arrived, she had completed every vocal and physical exercise, imaginable and unimaginable, to transform herself into a canine personality, and she was anxiously awaiting the other for the start of rehearsals. A new vista had opened before her. On all fours, she made faces and moved her mouth in ways that looked more like simulations of sexual escapades than the embodiment of a puny dog. For both of them, the script was the least important aspect. The one who was playing the dog from now on didn’t have a script, because dogs don’t talk. And the other one, who always had a knack for scripts, had a good memory. What would be hard was dying. She did every possible preparatory exercise—absolutely every one—for playing a role. But she couldn’t die for real to learn how to die in a play. She didn’t know how to die, which led to an insight. She didn’t know how to die; she didn’t want to die. Her daily portions of death had been used up in those eight years of playing a dog. It wasn’t the result of having played a dog, but because of the arduous experience of those journeys, because of the arduous work of making people believe that she was what she wasn’t, because of the sadness of those characters who would never see light because she had made the dog her calling. She had relinquished, in this way, being a medical student who commits suicide in a pool, in a short film by a new São Paulo director who had found success after starting out in advertising. This young man had invited her to play the role right in the middle of one of her tours with the dog piece. She relinquished the character before ever playing her. The same thing happened with other characters: the mother of identical twins, a Cuban prostitute in a Venezuelan film. She preferred the dog to the whore and the mother. She realized she could no longer tell where the woman left off and the dog began. When she barked, whose yelps were those? When she wagged her behind, which part of her brain was lit up? Or what if no part was lit up, because the work of playing this role had already become so automatic that it bypassed the brain? The Venezuelan, an excellent documentary-maker who depicted on film the socially marginalized of Central America, was so outraged by her refusing his invitation to play that Cuban prostitute that he slandered her publicly at a film festival. She ended up hearing about that and the next time she met him, didn’t hesitate to call him a son of a whore. The Venezuelan, a connoisseur of whores, was so outraged by this insult, very common in our culture, that he responded by losing control and screaming, “Mi madre inna whore! Mi madre inna whore!” And other things, too, had already happened. She herself had gone through various experiences during those years in the profession: she had slept in the street to play a beggar; she had seduced her brother for an incest scene; she had even cut—albeit lightly—her own wrists to play a suicide scene in an amateur video. But to die . . . to die, no. To die was the limit. In this hopeless mindset, she looked at her longtime companion onstage, and couldn’t be convinced. What her partner had done wasn’t fair. She shouldn’t have accepted this situation imposed by the other’s vanity. The dog was hers, was always hers. Now was no different. It never mattered to her that the dog was a role without a script. She found meaning in silences. She knew the significance of the dog for the lonely woman. She knew that, without the dog, the lonely woman would waste away. Over those eight years, she had constructed the faithfulness of a dog to his mistress. Even without any pride in being loyal, the dog was humanized in her guts, in her memory. There wasn’t a single day onstage when the dog wasn’t made to suffer by the lonely woman’s death, even if her partner didn’t play it with the dignity that the character demanded. She knew all of this, even despite not knowing how to die. She couldn’t die and let the dog live. The dog was her self. And since she was the dog, she wasn’t going to die as the lonely woman and make the dog suffer. This was one thing she knew for certain. Knowing this, she left the rehearsal. They found her, later, dead, surrounded by photographs of old characters, as well as a few of the dog. On that day, the surviving actress walked out of a small city’s auditorium crying real tears, while the people entering the theatre saw a naked woman on all fours trying to make a sound like the sad lamentations of a dog. The naïve spectators sat and remained silent for fifty-nine minutes, watching that woman. They understood nothing. They said nothing. And they would go to sleep sad. Was this what theatre was? They asked themselves. No one managed to sleep. They were very sad, very sad. They almost wanted to die.