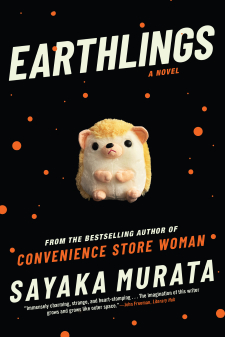

The real outcasts, then, are not those who embrace commercialized or co-opted forms of rebellion but rather those whose very makeup renders them unfit for modern society. This might seem to be the guiding idea of Earthlings, the most recent novel from the Japanese writer Sayaka Murata to appear in English (thanks to Ginny Tapley Takemori’s crisp translation). But Earthlings posits that “outcast” is in fact a slippery category. None of us truly belong to the so-called “majority”; instead we’re all aliens with a knack for performance. And Natsuki, who is just eleven years old at the beginning of the novel, is one of the rare few for whom this act of theater is impossible.

Earthlings opens as Natsuki and her family drive to a fictional mountain town for its Obon festival. Natsuki’s grandparents own a house there, and she loves the town for its traditions and natural beauty. Most of all, though, she enjoys the rare opportunity to see her cousin Yuu, with whom she has a close relationship. In his telling, Yuu is an alien hailing from the planet Popinpobopia. Natsuki believes him because, in her telling, she has magical powers. She also says that her stuffed hedgehog Piyyut (who talks to her throughout her childhood) was once a resident of Popinpobopia as well.

In a typical set up, the simple fact of Natsuki and Yuu’s difference would come to be the very thing that makes them special. One of the greatest appeals of many novels is that, because we are all the protagonists in our own story, we see ourselves as the special ones and readily identify with characters who are singled out—regardless of whether our hardships align with theirs. But Earthlings subverts this old formula. Natsuki and Yuu fail to escape formal society, and instead of a grand, redemptive journey, their lives are an endless struggle to assimilate. Natsuki’s only hope is that she be successfully brainwashed. Otherwise, the Factory—her name for Japanese society—will be on her tail forever. And she’s right.

And so the novel is rather cynical. Despite the bleakness of its message, Earthlings is not overtly misanthropic. Its satire is padded with a sense of earnestness. Natsuki’s innocence is a foil to those of us who have had enough of a taste of life to know what it’s really like. We’re familiar with the rigid expectations of work under capitalism, the policing of women’s bodies, the repressiveness of social taboos. As a child, though, Natsuki isn’t so jaded yet. She betrays a wide-eyed desire for normalcy even twenty years later, long after she and Yuu are caught having sex by the whole family, and long after a sexual assault leaves her unable to taste food or hear out of one of her ears.

In Convenience Store Woman, published in English in 2018 and also translated by Takemori, Murata deals with similar themes. In this earlier novel, the thirty-six-year-old Keiko Furukura desperately holds on to her part-time job at a convenience store because she doesn’t fit in anywhere else. She enthusiastically follows the demands of being a worker because she can’t fulfill those imposed on her for being a woman—such as finding a husband and having children. “I’d never experienced sex, and I’d never even had any particular awareness of my own sexuality,” Keiko says. “I was indifferent to the whole thing and had never really given it any thought.” In her thirties and single, Keiko is perceived as a suspicious figure. To counteract what she sees as her innate and irresolvable difference from other people, she sacrifices herself to the store, forfeiting her own personhood.

Earthlings offers less room for such decisions, which makes it more deterministic than Convenience Store Woman. Natsuki’s childhood, for example, is filled with abuse. Her mother and sister constantly berate her, and her cram-school teacher sexually harasses and assaults her repeatedly. Unlike Keiko’s origin story, which hints only at an inborn strangeness, Natsuki’s childhood places the emphasis on the inevitable effects of long-term trauma. Even though Natsuki is blind to her own psychology, the novel offers these traumatic events as touchstones. Her origin story gives the novel a strong sense of specificity, whereas Convenience Store Woman paints with broader strokes.

However tongue-in-cheek it may be, the latter novel focuses instead on the idea of work as salvation. Keiko applies to the convenience store on a whim and quickly becomes entranced by its simplicity. “A convenience store is a world of sound,” she says at the beginning of the novel, where everything from the “door chime” to the “voices of the TV celebrities advertising new products” to the “calls of the store workers” comes together in harmony. Her newfound bliss brings to mind the oft-repeated Mark Twain quote: “Find a job you enjoy doing, and you will never work a day in your life.” Keiko takes this to its natural conclusion: her work becomes her life, and her life outside of work is nothing but endless toil.

Natsuki, at least in the beginning, has more traditional fixations. Aside from the taboo of their being cousins, her and Yuu’s sexual curiosity is typical for kids their age. Yuu hesitates at first, but Natsuki convinces him that physical intimacy will strengthen their bond. The novel’s flashpoint is their decision to have sex. The family catches them, and both are punished severely:

Yuu and I were ripped apart, and I was thrown into the storehouse. I briefly caught sight of him by the rice fields being beaten as they dragged him off. All the aunts and uncles, plus Mom and Dad, were more upset than I’d ever seen them before. I found it all ridiculous.

They don’t see each other again for more than twenty years.

Earthlings fixates on these taboos, charting how the expectations we face dictate our relationships. All the familiar archetypes appear: the nagging mother, the aloof father, the cool uncle. And we have the outcasts, like Natsuki and Yuu, who feel so alienated from the world that they convince themselves they’re either magic or visitors from a foreign planet. In one brief scene, Natsuki watches her mother at work, where she is generally disliked and called “Godzilla Sasamoto” behind her back. The suggestion is clear enough: the controlling mother is also a controlling colleague, but the difference is that her colleagues have just as much power over her as she has over them. To Natsuki she’s a real monster, but in reality she’s just another woman making the best of the difficult hand she’s been dealt.

Both Earthlings and Convenience Store Woman are strengthened by their close attention to such gendered expectations. Twenty-three years after the incident with Yuu, Natsuki is married to a man named Tomoya. They live close to Natsuki's family in Chiba, working temp jobs to make rent. The problem is that theirs is a marriage of convenience, not love. Tomoya is just as wary of the Factory as Natsuki, if not more so. Their agreement forbids physical contact of any kind, let alone sex, and they sleep in separate rooms, electing to split the household chores evenly and keep to themselves. The benefit is obvious: since they’re technically married, their families will be off their backs. At least until they’re expected to start a family of their own.

Convenience Store Woman features a similar relationship: Keiko eventually enters into a partnership with her former coworker Shiraha, who disdains women and rambles on about the Stone Age. He is rude and condescending to Keiko, insisting that his situation is far worse than hers. Yet she eventually realizes that by letting him crash at her apartment she can simulate a real adult relationship. Shiraha takes advantage of this generosity, but Keiko considers it a fair price for helping her fit in.

Tomoya is far more sympathetic than Shiraha, and however much Murata is concerned specifically with the plights of women, she is clearly attuned to men’s unique struggles as well. Natsuki and Yuu finally reunite when she and Tomoya convince her family to let them take a short vacation in Akishina. Yuu, who recently quit his job, stays in the house alone, but Tomoya’s presence reassures the family that nothing inappropriate will happen. At first, Yuu resents Natsuki for her childishness. Although she and Tomoya have managed to elude the Factory’s grasp, Yuu has been completely brainwashed. Despite living off his family’s land, he still feels the pressure of living a respectable life. But he soon gets on well with Tomoya, and eventually he slips back into his old patterns. The three of them then begin to enjoy a steady, cooperative life together out in the country.

Naturally, the family catches on, and the trio realizes that their escape is only temporary. No matter how self-sufficient they are on the fringes of society, their families’ shame is too great. The sole remaining exit strategy is denouncing personhood itself, much as Keiko did when she sees herself as worker first, person second. But instead of the honorable route, Natsuki, Yuu, and Tomoya go full speed ahead into the land of taboo. When Natsuki’s family eventually arrives at the house to investigate, they find Natsuki, Yuu, and Tomoya on the floor, all half-eaten, with human flesh in their mouths. Through self-mutilation, they have transcended.

Where Convenience Store Woman sticks to the stoic realism of Keiko’s work obsession, Earthlings derives its power from these moments of fabulism. Murata’s writing remains straightforward and restrained, but it’s rewarding to witness a creative mind become less tethered to the bounds of everyday life. The novels diverge in their treatment of transgression within a strict, homogenous society. One celebrates the power of work—of obediently fitting in wherever one can. The other, however, lauds the power of taboo and sacrifice—of freedom at all costs. Earthlings, then, is bleakly cathartic: there’s nothing more freeing than the fantasy of escape.