Matt Reeck’s English translation, French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony (2020), has broadened the readership of this photo-text twenty-six years after its original publication. As a book that originally debuted in the early 1990s—when French intellectuals engaged in “memory debates” after the 1989 bicentenary of the French Revolution—it addresses the erasure of colonial history from the nationalist narrative, a topic pertinent to this very day. One example of such historical silencing is found in the monumental Les Lieux des Mémoires (Realms of Memory) project, a multi-volume collection of one hundred and thirty-three articles published between 1984 and 1992, spearheaded by Pierre Nora. The project laments historiographic trends that interrogate established domains of common knowledge within France’s national memory since they result in historians no longer unquestioningly identifying with the most revered, eventful elements of the French tradition. While Nora’s project sought to resist what he perceived as history’s besiegement of memory, the colonial question was conspicuously omitted from the project’s purview. French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony, in contrast, works against such academic tendencies evident in Western commemoration practices by taking seriously Creole memory practices and developing the neologism of the “Memory trace,” which challenges static triumphalist metanarratives of national history.

By reckoning with violent histories of displacement, incarceration, and extermination, French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony offers today’s Anglophone readers an opportunity to explore ongoing practices of colonial commemoration. This timely publication arrives during an era in which French governmental and academic institutions have recast a spell of collective amnesia. In early 2021, leaders within the Macron administration issued attacks against critical studies of racism by resorting to the politically convenient argument that leftist U.S. academics import anti-racist ideology into France. Such bogus claims belittle the critical interventions of France’s decolonial social movements, migrant worker and refugee struggles, uprisings in the banlieues, and French-speaking thinkers from across the overseas territories.

In contrast to the visual economy of prison imagery that is produced and consumed in today’s media, which depicts prisons fully operational, Hammadi’s photographs offer us rarely seen glimpses into decrepit penitentiary ruins, allowing us to visualize the prison as an ancient artifact. This distinctive prison visuality dovetails well with today’s social movements shaped by people who are collectively envisioning how a world without prisons might look. The reflective engagement with obsolete carceral debris, as exemplified by this photo-text, will prove informative to anyone wondering what will become of the prisonized landscapes we currently inhabit. While it is in the interest of some conservationist groups to prevent further deterioration of penal heritage sites, as historian Sophie Fuggle has noted, the question of whether ongoing investment in carceral monument preservation reinforces and justifies the punitive logic of the prison-industrial complex warrants further consideration.

Equipped with supplemental materials, French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony opens with a foreword by Charles Forsdick and a translator’s note by Reeck, to introduce the main essay by Chamoiseau and the series of over fifty color photos by Hammadi that follow it. While Forsdick offers a broader background into the Guyanais penal colony and explains the significance of Chamoiseau and Hammadi’s hybrid project, Reeck describes the challenge of translation in the poetic, theoretical, and historiographic terrain of Chamoiseau’s sonorous prose. The essay by Chamoiseau first introduces readers to the poetic concept of Memory traces—which are ever-evolving material, symbolic, and/or functional elements that possess unfathomable meanings, by virtue of bearing witness to histories of demolished memories in a given environment. Afterward, the essay offers various examples of Memory traces across the penal colony and closes with a call to action for conservators to work against the site’s degradation. The sequencing of Hammadi’s photographic images constitutes a non-linear visual narrative with thematic through lines that juxtapose interior with exterior, iconicity with anonymity, and life with death, among other motifs.

The translation of French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony raises questions about the role of photography in literary translation. Does the translation of a photo-text risk privileging essay writing at the expense of the non-verbal meaning possessed by photographs? By virtue of placing Chamoiseau’s essay before the main sequence of Hammadi’s photographs, as opposed to interspersing them, the book design itself (in the original and translation) places chronological emphasis on the essay. But Reeck’s translation is just as attentive to the book’s visual elements as it is toward the textual. By delicately intervening between the interplay of photo and text, Reeck’s lucid translation assuages hierarchical tensions that occur between the two media.

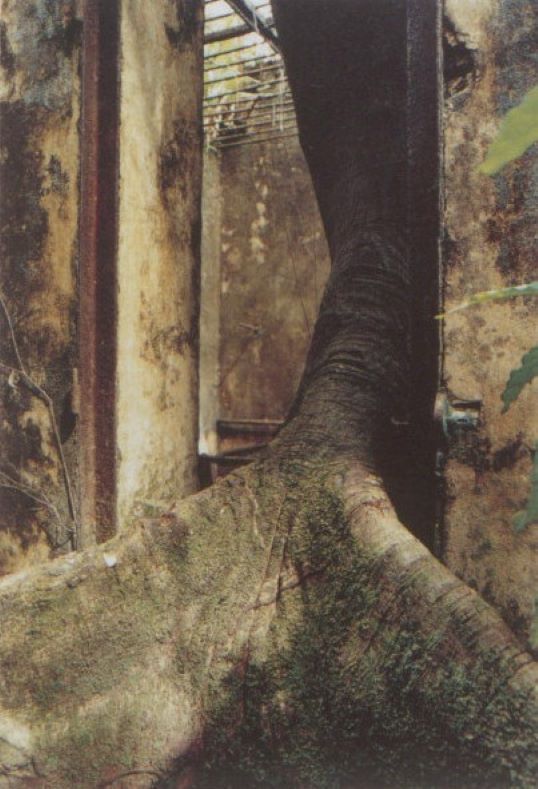

While Chamoiseau’s essay theorizes how Westernized heritage commemoration silences the memory of France’s most marginalized communities, Hammadi’s photos do not simply illustrate his argument, they also complicate it. Deeming national monuments, statues, and archives as incapable of capturing the histories of Creole people, and non-Western societies more generally, Chamoiseau turns toward a Caribbean framework of considering the landscape to be its own kind of monument. “Beneath the texts of colonial History . . . beneath the lofty Memory of forts and buildings,” he writes, “we must now learn to recognize, to catalog, and to explore in the aim of patiently weaving together the open complexity of our creole patrimonies.” Correspondingly, Hammadi’s uncanny conflation of human and natural structures in his photographs often results in images that look past the decayed prison ruins, and into the flourishing Amazonian plant life that overwhelms and consumes sections of the defunct penal architecture. But while some photographs serve to revindicate the points Chamoiseau makes in his essay, other images appear to contradict them.

Photo by Rodolphe Hammadi

Chamoiseau eschews historical approaches that rely on iconic historical figures because, as Reeck explains in the translator’s note, his notion of the Memory trace is premised on an affective approach to history that recovers forgotten pasts of those who endured domination. In this vein, Chamoiseau critiques forms of memorialization that restage overrepresentation and instead emphasizes how our awareness of collective histories, in the context of mass criminalization, should not come at the cost of making individual histories hypervisible. Yet while Chamoiseau’s essay contends that the penitentiary walls are not witnesses to “individual presences” but instead “a haggard mass,” some of Hammadi’s photos suggest otherwise. The slight dissonance between some of the images and the essay illustrates how Creole commemoration practices are at odds with the penal heritage practices of the CNMHS, which rely in part on iconic attractions.A few of Hammadi’s photographs, and their accompanying captions, initially appear to contradict Chamoiseau’s observation. Notably, the sole photograph which centers graffiti in this text features the word “Papillon” crudely etched into a solitary confinement cell’s discolored concrete wall, darkened by the abrasion of untold fingertips. The marking, a modern prison petroglyph, references the nickname of Henri Charrière—a young man from the provincial region of Ardèche who migrated to Paris, where he was framed for homicide by police and sentenced to lifetime imprisonment in Guyane. As a formerly incarcerated person, he reached celebrity status after escaping the penal colony and publishing a memoir, Papillon, that has been adapted into multiple Hollywood movies over the years. Now, much like the distressed concrete upon which his name is graffitied, he too is but a ruin of his former self, as his wall markings have become relics.

Another pair of Hammadi’s photos that contrast with Chamoiseau’s comments on individualistic memorialization depict “Alfred Dreyfus’s house” and “Dreyfus tower,” a group of images that effectively bookend the photography section of the photo-text. Alfred Dreyfus was a French military officer of Jewish faith and ancestry who was wrongfully convicted in a secret court martial for treason and whose case became emblematic of nineteenth-century French anti-Semitism. Dreyfus’s house is depicted from two distinct angles, the interior and exterior. The former shows the cracking yellow and off-white interior walls looking out toward a small exposed wooden and brick window frame that in turn looks out to the Atlantic Sea and a nearby palm-tree-studded coastline. The latter depicts the exterior façade revealing that the house has no roof, no windows on one wall, and is surrounded by piles of stones. The four-story tower decked with arched floor-to-ceiling stone-framed windows is seen from the exterior with an upward tilted perspective against the backdrop of a blue sky. Such iconic images belie Chamoiseau’s claim that individual presences cannot be retrieved from the penal colony ruins. In fact, formerly incarcerated people who gained widespread notoriety are perpetually centered in the authoritative historical narrative.

Matt Reeck’s translation practice goes beyond Chamoiseau’s essay and extends to the book’s paratext, as photograph captions bridge the gap that results from the redeployment of images. In the original text most, but not all, of the photos are accompanied by Hammadi’s informational captions, which simply describe the location where the photograph was taken. But there are a few captions that make use of quotes from the essay. Through this visual-textual collage technique, Hammadi revalidates some points Chamoiseau makes. The numerous photos of French words with a “penitentiary rhythm” painted on the walls (Quartier Disciplinaire, Blockhaus, Cellules) illustrate how such signage, as Chamoiseau explains, “indicates places that have lost their initial function and are now suspended in half-fantasy.” In another image, a huge ceiba tree growing through the walls of Saint-Joseph Island’s disciplinary quarters is captioned by a Chamoiseau quote that observes how the plant life appears to suck the lifeblood out of the structure’s stone and cement. Assuring that no visual goes uncaptioned in the English version, Reeck adds descriptive captions to numerous images which have none in the original French. Reeck’s translational captioning of photographic images makes them easier to appreciate for viewers and readers who encounter not only a language barrier when observing them but are also separated from their provenance by virtue of historical time.

Photo by Rodolphe Hammadi

Photo by Rodolphe Hammadi

Reeck’s graceful rearrangements of syntax, fidelity to Chamoiseau’s neologisms, and acknowledgment of untranslatability, accurately maintain the essay’s original meaning. Upon contrasting the French and English versions, bilingual readers may notice that Reeck occasionally opts to keep intact several French loanwords, as well as vernacular names for culturally specific objects. Nevertheless, he faces a challenge in maintaining subtle, intertextual allusions that tie the essay to the wider world of authors of French literature. For instance, Chamoiseau’s usage of terms like hoquets, aliénation, and flâneur, which indirectly allude to figures ranging from Léon-Gontran Damas, Frantz Fanon, and Charles Baudelaire, is lost in translation. But this minor omission pales in comparison to the more significant omissions made not by Reeck but by Chamoiseau himself, which have been pointed out by French studies scholar Andy Stafford and sociologist Clémence Leobal. For instance, Stafford has pointed to Chamoiseau’s omission of how the penal colony became reserved for Black and Asian persons after doctors practicing biological determinism concluded that the subtropics were disproportionately harming incarcerated White individuals. Additionally, Leobal has critiqued the text for glossing over the presence of migrants and refugees who actively inhabited the penal colony ruins long before and during the co-authors’ visit.Even so, this book is just as important as a contribution to Francophone Caribbean literary studies, as it is to memory studies, cultural heritage studies, photo-textual studies, and carceral studies. An outstanding review of Reeck’s translation was published by Piper French in the Los Angeles Review of Books shortly after it was released. However, the unfortunate timing of the book's publication, which coincided with the onset of our ongoing public health crisis, has likely interfered with its broader reception among potential reading audiences. What relevance does a photo-text from 1993 of a late-nineteenth-century French penal colony in South America have for twenty-first-century Anglophone readers? The fact that French Guiana: Memory Traces of the Penal Colony came out the same year that memorials to Confederate soldiers, Columbus statues, and other colonial monuments were toppled in the wake of anti-policing protests demonstrates the ongoing relevance of debates on public commemoration and state violence. As a challenge to the French state’s official account of the penal colony heritage site, it offers a useful framework for analyzing institutional monuments to structural racism, such as prison museums and other heritage sites marked by carceral memory.