Like Chandrabati, Dev Sen also produced poems. In the same interview, she remarked that in British India, where she was born and schooled, most Bengali poets were teachers of English but made a political decision to write in Bengali. Acrobat, recently released by Archipelago Books, presents to English readers a retrospective collection of poems by Dev Sen. Like her predecessors, Dev Sen chose to write in Bengali, but was also quite capable of writing in English, which she sometimes did, in addition to occasionally translating her own poems into English. It is a testimony to her versatility as a poet, and to the skill of translator Nandana Dev Sen (another daughter), that without the notes identifying which poems were originally written in English and which were the translations done by the poet herself, it would be impossible to know the genesis of the texts we have before us.

Dev Sen’s poems are short, ranging from a few lines to at most a few pages. In many cases, they present snapshots of a life that is perhaps the poet’s, but, importantly, also anyone else’s. Take, for instance, “Unspoken,” presented here in its entirety:

Each time you say,

“Forever, forever,”

I only hear,

“Today, today!”

This is a concise jewel of a poem. In less than a dozen words Dev Sen wraps up and hands to us a moment of truth for two lovers: the one claiming eternal love, the other accusing the first of insincerity. At the risk of falling into a stereotype, I would venture that he insists on forever, while she tells him that she is on to his game. Of course, what Dev Sen does not do, and what makes this poem work so well, is reveal what happens next. By refraining from giving us a fifth line or even a twelfth word, she leaves us with the turmoil and pain that have been repeated since the beginnings of humanity (although the genders of the speakers have most certainly varied) and that will surely be repeated to its end.

“This Child” is a little longer—eleven lines rather than eleven words—but similarly captures a predicament as common as motherhood and as singular as the birth of a child. It begins:

One day this child too will die.

This child, pure as milk . . .

What mother would say such a thing? I would suggest: every mother, perhaps not always at the child’s birth but certainly at some other point. With that first line Dev Sen captures the burden of giving life, the terrible responsibility of bringing another being into the world.

A few lines later, Dev Sen turns to ask how she will face this child who will inquire why she brought her into the world despite knowing death would be her lot:

If she asks me now, “On what promise

have you thrust me into this strange and dazzling world?”

. . .

I will run away

to a dark cave, numb and empty.

But Dev Sen is not bewailing this birth; she does not melodramatically condemn the girl to a life of tears, nor castigate herself for bringing a child into the world. Though she clearly does not wish to, she tries to face the painful and universal truth that, however much she loves the girl, what will become of her cannot be known, save that she will one day die.

Although “This Child” begins with the startling affirmation that the child is destined to die, the poem is also full of life. The “strange and dazzling world” Dev Sen evokes in this poem is everywhere throughout Acrobat. Often, she presents this world to us framed in twilight, so that it becomes all the more dazzling and we cannot but pay attention. In “These Beloved Faces,” for instance, Dev Sen laments witnessing how those she loves age: “How everything dries, / how everything flies away in the wind.” Yet even amongst these images of desolation—the “brows [that] collapse like a dead bird’s wings,” the “lips dry as dust” and the “scraps of paper”—she also writes that:

The heart retreats and folds, as I now see,

it takes all shining pots and pans from the rack

and shatters them on cold stone with a deafening crash.

Suddenly, everything is alive and bright and noisily crashing: anger, revolt, grief, pain, yes, but especially life—or at least momentarily, until “in the heat of the sun, all sounds fade away.” This, I think, is the heart of this collection: Dev Sen always finds a way to surprise us with life, only to remind us that we are finite. In the title poem—about an acrobat who “would glide, so smooth, along the tightrope, / She thought she could do absolutely anything at all”—such a moment arrives in an arresting image: “Only once in your life will the rope shiver.” However accomplished we may be, however powerful we imagine ourselves, our lives reach their conclusion.

My only quibble with this collection—and it is a minor quibble, but reviewers need to quibble to demonstrate that they are paying attention—is its organization. The poems are grouped into five sections: “The Unseen Pendulum,” “I Cage Language,” “Sapling of a Heart,” “Do I Know this Face,” and “Sacred Thread.” “I Cage Language” seems to promise poems about language, poems about poems and poets, and even poems about the wonder and the futility of the art. And it does do all that, as in “A sad song about words”:

Like landed gentry, flawlessly attired,

words step gingerly into

the grand carriage of your imagination,

avoiding the muddy pavement

of your pen.

But this section also includes poems like “Unspoken,” discussed above, that do not appear to fit into what, at least to my mind, is the stated category or theme. I wonder if this retrospective of Dev Sen’s poems needed to be grouped at all, especially given that the organization doesn’t seem to add to the individual poems or to the collection as a whole. Yet I am thankful that the book includes at its end a chronology of the poems. Although it is perhaps a less elegant organization of the poems, it is a simpler and more straightforward one. I would have much preferred it since it allows me to follow Dev Sen’s path as a poet—or at least tell myself that I can.

It is no accident, I think, that in her final collection this poet, who made the political decision to write in Bengali, changed the title of a poem she had already published in English in 2013, in Make Up Your Mind: 25 poems about choice. Here is the poem in its entirety:

Man: In the twilight, I could still hear the lark

Woman: The night was moonless, oppressively dark

Man: In the flowering woods, a night fairy walked

Woman: In the Sundarbans the man-eater stalked

Man: In that fragrant springtime air

Woman: Blood-drenched remains lay there

In Acrobat, “The Night of the Rape,” as it was known in the earlier collection, has become “Take Back the Night.” Nothing else has changed in the poem, but the new title has transformed it. How different this poem with its direct reference, not to the crime, but to the nonprofit dedicated to creating a world free of such crimes! The 2013 version presents the crime, making us face the uncomfortable truth that Man and Woman do not inhabit the same world: he walks freely; she treads through darkness in fear. The final version published in Acrobat says all of this as well, but with its new title it becomes even more clearly political. It exclaims: “Enough! We won’t stand for it any longer!” This is the Nabaneeta Dev Sen in whom activist, feminist, and poet are one, and to my mind, this is her lesson to those who succeed her.

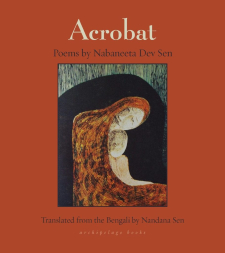

Acrobat offers us a window onto the many persons Dev Sen became, and continued to become. Yes, continued to become: the evidence in Acrobat makes it clear that, for all her accomplishments, she never rested on her laurels. In her afterword, translator Nandana Dev Sen remembers her mother’s delight on receiving the cover design for the book: a painting by one of those grown-ups who visited her childhood home: Rabindranath Tagore, who, eighty years before, had chosen the future poet’s name. “This is my first book published by a truly international press,” Nabaneeta Dev Sen exclaimed. “I’m definitely going to stick around for this one!” Sadly, she did not. Ten days later she died, without ever presenting this wonderful collection to the English-speaking world herself.