I remember my four days in Florence with an exceptional clarity that I often fail to summon for yesterday’s events and that I certainly cannot claim for the other cities I traveled to that summer. I vividly recall the peculiar gait of an Asian woman at the Uffizi Gallery, her phone drawn close to her like a shield protecting her from Botticelli’s Primavera. I fondly remember sitting on the patio of a restaurant by Piazza San Lorenzo, savoring each bite of my penne alla vodka while taking pleasure in—without understanding—the lively dialogue between four young people next to me. As if it were right before my eyes once again, I see a small wedding entourage passing by the Ponte Vecchio happily and sweatily. Solitude, I suspect, refined my powers of observation, which in turn left me with more intense memories.

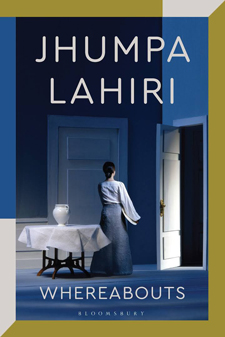

The narrator of Jhumpa Lahiri’s third novel, Whereabouts, is an observer whose powers emanate principally from her solitude. Like so many contemporary, realist, first-person narrators, she scrutinizes the louder and crisper characters surrounding her while only revealing herself in reflections and refractions. Our encounter with her is thus of a vicarious sort. Each chapter bears the title of a “whereabout,” with some specifying physical locations—like a ticket counter, trattoria, hotel, or crypt—and others evoking states of mind—like dinner, vacation, springtime, or August.

The people she sees with some regularity include a young woman from abroad who has resolved to stay in Italy without her parents; a friend’s husband who, in another life, might have been a romantic partner; and a friend who visits the narrator’s apartment to decompress from the chaos of her family home. There is also a large cast of characters who she does not know personally yet towards whom she displays a sincere tenderness: the chatty, older women she encounters in the changing room for the pool; a stunning beautician who carefully lacquers her nails; and a serious and sympathetic philosopher at an academic conference with whom she shares elevator rides. Her self-described solitude is most noticeable not in her isolation or withdrawal from the world, but in how deliberate she can be about who she sees and when. The narrator’s portrayals of people, places, and feelings are never innocent; each one represents an interrogation into her own pleasures, interests, and irritations. Each observation is also an appeal to readers to consider what kind of mental constitution she must possess to produce her particular appetite for dissecting the world.

In the vignette “At My House,” the narrator recounts a visit that an old friend from out of town makes with her husband. She meets the husband for the first time, and he does not have to say much for her to decide that he is “pompous,” unattractive, and without sensitivity. She is disgusted by the way he makes a show of evaluating her while scanning her bookshelves, and she refuses to lend him a favored volume that piques his interest. Her petty hostility toward this man is admirable; she refuses to let the life she has made for herself be overrun by significant others, children, or families. Yet the power of refusal has its limitations: the narrator’s friend is absent and distant in the presence of her husband, and the husband has conveniently bid the narrator adieu without mentioning the ugly, black line that his daughter has drawn onto her couch. This short scene, rendered with sparse clarity, is mundane yet dramatically tense. The narrator’s tangible control over the situation wanes, so she seizes authorship in another way: through her discerning gaze.

In all the vignettes, the narrator’s solitude is ambivalent. It reliably sets her apart from those around her, but that same distance allows her to observe with singular acuity. She considers this solitude in an early vignette titled “In My Head,” which frames a rift with her mother through their differing stances on what it means to be alone.

She’d say solitude was a lack and nothing more. There’s no point discussing it given that she’s blind to the small pleasures my solitude affords me. In spite of how she’s clung to me over the years my point of view doesn’t interest her, and this gulf between us has taught me what solitude really means

This succinct report on the narrator’s relationship with her mother contains a personal statement on who, in adulthood, she has wished to be in relation with others. Like her mother, most people yearn to find someone—anyone—to cling to. Therefore, an unbridgeable chasm lies between the narrator and almost everyone else. Those who have found long-term partners, co-dependent friendships, and children—and who have thus bandaged their existential loneliness—look upon solitary people as liminal figures, even as solitude is a condition that is often intentionally forged. Respect between that kind of person and a solitary person cannot be mutual—or at least not in a way that is ever fully satisfying to the latter.

A run-in at the bookstore with her ex compels the narrator to recount the bizarre revelation that ended their five-year relationship, which had developed in a domestic pattern. She had cared for him when he fell ill, cooked elaborate meals to please him. She never second-guessed the inevitability that he would propose. But, incidentally, she discovered that he had covertly maintained a relationship with another woman for those five years. Together, she and this other woman retrace the lives that they improbably and simultaneously led with the same man. Disturbed, she nevertheless divulges that, “even as my life shattered in pieces, I felt as if I were finally coming up for air.” Although she witnesses the sunset of a homely life with her partner, her autonomy is finally restored.

This discovery belies more than the uncomplicated demeanor of a man she thought she had known. It produces the kind of visceral shock that reminds her—and us—that we can never know people as well as we think we do. The choice to surround ourselves with others can be vital, but becomes fatal when those people serve as props in a neutering operation. Those prone to Freudian readings of human decision-making—who tend to see every unconventional choice as attributable to deep and irreversible psychological trauma—might pin the narrator’s solitude on maternal envy and the pain caused by this duplicitous ex. Of course, the pervasive compulsion to settle in lackluster relationships and staid marriages—the generalized nervous condition of being unable to spend time with oneself in contemporary society—should also prompt the intervention of clinicians. Yet the preference to be single is always identified as a deficiency—or, worse, the result of psychological trauma.

The narrator’s resistance to taking people for granted is the condition of possibility for her writing. Her descriptions of people and places evince an attentiveness to her instincts. Relaying her distaste for the hotel in which her academic conference takes place, she excoriates it for looking like a “parking garage designed for human beings instead of cars.” The piazza transforms into a beach, the narrator claims, as it conveys the atmosphere of spumante that suffuses public space on a Saturday in early summer. Her prose is exacting in its effort to reverse engineer a feeling that always arrives before any language can be applied to it. That perceptiveness to herself and others cannot be sustained if who she is, and who others are, is a foregone conclusion—which often becomes the case when we become too comfortable in our belief that the distance between ourselves and others is nil.

The narrator deliberately reproduces the alienation between herself and others. At some points this means being elliptical or evasive: the character that appears most frequently in the novel is a friend who she introduces as “a man I might have been involved with, maybe shared a life with.” Later, when she spots him with his wife on the street, she remembers to clue readers in on his identity, referring to him as “the kind man I cross paths with now and again on the bridge,” referencing an earlier scene. And in a vignette toward the end of the novel, the narrator joins her friend and his kids on a day trip to a castle. “He’s my friend from the bridge, the one quarreling on the street, the one from the supermarket,” she explains offhandedly, in the manner of a footnote. This man is the only character that readers meet semi-regularly. But she doesn’t tell us his name or their mutual history, and we accept the hint that she doesn’t want to properly introduce us. Her feelings toward him are ambiguous, and in place of more forthcoming judgments or disclosures, she writes politic sentences like: “He always looks happy to see me,” or “He’s a good man.”

Some of these sentences, granted, might log as overly simple and unsophisticated. Whereabouts is Lahiri’s first novel written in Italian and she took the further step of translating the novel into English herself. It would be remiss not to mention Lahiri’s unusual commitment to writing in Italian, which she detailed in In Other Words, a collection of essays she wrote in Italian in 2015—her first work composed in that language. That book represented an extended love letter to the country, the people, and the language. It also probed her growing disillusionment with writing in English, and the burdensome demand for perfection she experienced alongside it. Lahiri analogized herself to the Greek nymph Daphne, who morphs into a laurel tree to evade the sexual pursuit of Apollo: “I am, in Italian, a tougher, freer writer, who, taking root again, grows in a different way.” Yet this freedom is contingent on self-imposed limitation. “I have to accept that in Italian I’m partly deaf and blind,” she writes.

At times Lahiri’s prose reads as stilted. She frequently strings together independent clauses with commas, contributing to the general impression of fragmentation and keeping readers an arm’s length away from the scene. I can see some of the glints of the “freedom to be imperfect” that she claims Italian affords her in Whereabouts. Maybe the narrator is tight-lipped about the complexities of the relationship she has with her married friend because they are trickier for Lahiri to convey in Italian. But perhaps a casual phrase like “he’s a good man” also says quite enough.

Lahiri’s commitment to writing solely in Italian often strikes people as monastic. But it begins to make sense in Whereabouts. In the same way that a considered estrangement from people and place can be necessary to reenchant a person’s relationship to the world, a radical refiguring of a person’s all-too-familial relationship to their native tongue can imbue life with new a artistic agency. Here is a writer who is serious about how life can be enriched by distances, silences, and the unfamiliar—not as a matter of self-denial but of life affirmation. I shudder at the reviews of Whereabouts that fixate on interrogating the narrator’s sadness, as if sadness must be unremittingly avoided, as if the lack of people in her life is synonymous with sadness. These discussions not only treat the narrator’s direct statements on her solitude as unreliable but also call into question our stubborn resistance to believing people when they tell us they like spending time alone.

Lahiri’s novel evidences some of the fruits of solitude—pregnant language, remarkable attentiveness, and freedom. Perhaps the most surprising fact about Lahiri’s narrator is that she has lived in the same town all her life. Again, Lahiri seems to emphasize that her outsider status is not imposed—it is chosen. But her patterns of being and movement through her hometown have solidified into something too rigid, and perhaps even her solitude has become too well-trodden. By the end of Whereabouts she makes a transformative decision to uproot herself, and as she sits in her train car, she observes a group of people exuding mutual fondness and energy in another language. Her description is uneasily anthropological; it gave me a bit of a jolt, and reminded me that estrangement, just like familiarity, can become monotonous.

I savored my solitude in Florence while it lasted. I left with memories of faces, architecture, and soundscapes. But I was also ready to experience what new attitudes new places could bring me. As I finished Whereabouts, I found myself hoping that, like me, the narrator would someday have the chance to stumble upon something new.