Ottilie Mulzet translates from Hungarian and Mongolian. Her translation of László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below won the Best Translated Book Award in 2014. Her recent translations include Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens by László Krasznahorkai (Seagull Books, 2016); The Dispossessed (HarperCollins, 2016); and Berlin-Hamlet by Szilárd Borbély (NYRB Poets, 2016); forthcoming is her version of Lazarus by Gábor Schein (Seagull Books, 2017), as well as Krasznahorkai’s The Homecoming of Baron Wenckheim (New Directions). She is also working on an anthology of Mongolian Buddhist legends. In 2016 she served as one of the judges of Asymptote’s Close Approximations translation competition and is on the jury for the 2017 ALTA National Translation Award in Prose.

Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Slovakia, Julia Sherwood, spoke with Mulzet via email. Below is the first part of their enlightening correspondence. Stay tuned for part 2!

Julia Sherwood (JS): You translate from the Hungarian, are doing a PhD in Mongolian and are based in Prague. Your recent Asymptote review of Richard Weiner’s Game for Real shows that you also have an impressive command of Czech, enabling a close reading of the original and an in-depth review of the translation. How did your involvement with Hungarian begin and what is it like to live between all these languages?

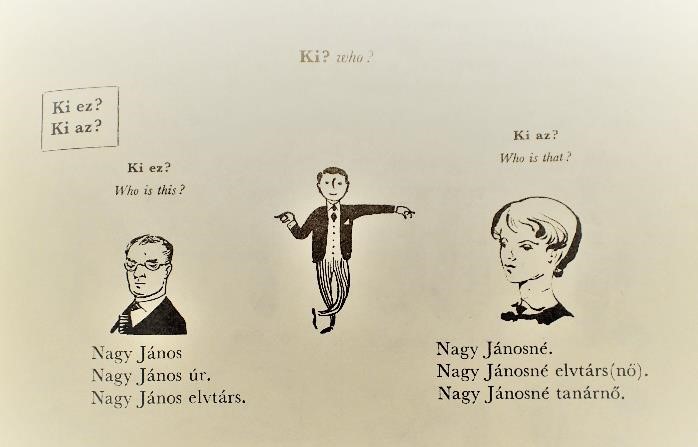

Ottilie Mulzet (OM): Part of the difference is due to my involvement with each of these languages. I started studying Hungarian because of my family background (two of my grandparents emigrated from Hungary), although I didn’t speak it as a child. I decided to learn it in adulthood as the result of some kind of fatal attraction, I guess, and never even realized I would end up translating. Hungarian grammar struck me as being so strange that I couldn’t wait to get onto the next lesson to see if what followed could possibly be any stranger than what I just learnt. I used a hopelessly out-of-date textbook with pen-and-ink illustrations of women in 1950s coiffures having a cigarette in front of a prefabricated housing estate. They spent their evenings complimenting each other on their clothes, sipping tea and playing match games, all the while making sure they were back at their parents’ houses by 8 pm. In retrospect, this textbook actually encoded, along with Hungarian grammar, a manual to the kind of “petty bourgeois-dom” that was so characteristic of central European socialism in the 1980s.

An illustration from my first Hungarian textbook. Here we are introduced to Mr. Comrade Nagy, and his lovely wife, Mrs. Comrade Nagy.

I learned Czech more for practical reasons, because of living in Prague, but there are many aspects of the language I’ve come to love, not least its humour and slang. I try to keep up with what’s going on in Czech literature, although I don’t translate from it. One of the most amazing things about learning Czech is that it has enabled me to study Mongolian—at Charles University, an institution with extraordinary language pedagogy with roots in the pre-war Prague Linguistic Circle, and an astonishing array of languages on offer—from Manchurian and Jagnobi (a descendant of Sogdian) to Jakut and Bengali. One can only hope, given the current trend toward mindless rationalisation, i.e. shutting down whatever seems too impractical or exotic, that the university will stay that way. It’s impossible to understand anything really essential about another culture without knowing something about the language: and the more you know about the language, the better off you are.

READ MORE…