This month, our selected titles of new publications carry wisdom, mystery, and humour. Below, find reviews of plays by one of India’s most accomplished and innovative playwrights; a compilation of interview with the inimitable Etel Adnan, conducted by Laure Adler; and a PEN Translates Award-winning novel of revenge and self-discovery, set in the Abbasid period.

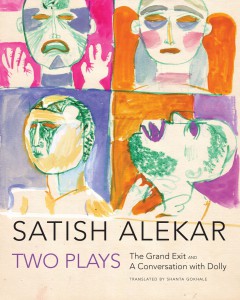

Two Plays: The Grand Exit and A Conversation with Dolly by Satish Alekar, translated from the Marathi by Shanta Gokhale, Seagull Books, 2024

Review by Areeb Ahmad, Editor-at-Large for India

This nifty volume of plays collects two of Alekar’s works, “Mahanirvan” and “Thakishi Samvad”, written forty-six years apart—Born in 1949, Satish Vasant Alekar is a Marathi playwright, actor, theatre director. He was a founding member of the Theatre Academy of Pune and is well-known plays such as for Mahapoor, Begum Barve, Atirekee, and Pidhijat. He is considered among the most significant playwrights in modern Marathi and Indian theatre, along with Mahesh Elkunchwar and Vijay Tendulkar, and lately, he has come to be recognised for his acting in Marathi and Hindi feature films.

“Mahanirvan” or “The Grand Exit” was first performed in 1974, and is a play where a dead man has more dialogue than any living character. The description on the cover is not wrong to equate the character with Sophocles’ Antigone, for he also strongly insists on the method of his last rites; Bhaurao wants to be traditionally cremated at the shamshan ghat, but the cremation ground is in the process of being privatised. Thus, the dead—or rather their relatives—are now being redirected to a new facility which uses electrical incineration.

So Bhaurao lingers around as his body malingers, rotting and fly-infested, while his wife Ramaa grieves intensely, coming to terms with the sudden loss, and his son, Nana, tries to convince him to just go ahead with the cremation, and pass on. While working on the play, Alekar had realised that a dead man cannot speak prose, so Bhau’s dialogues instead take the poetic form—one resembling keertans (religious recitations). READ MORE…