Posts filed under 'Interview'

Asymptote Podcast: Favorite Readings of 2017

Start out 2018 right by taking a listen to our favorite readings published over the last year.

On Editing an English Literary Journal as a Person Of Color

The matter-of-fact, even slightly cheerful, answer: "Have your characters come to the US!"

Hello! (Taps mic…) Our regular blog editors Madeline, Hanna and Nina are on leave today, so I’ll be guest-blogging to continue our daily programming. My name is Yew Leong (yes, that’s two words for my first name) and I’m the Singaporean editor working behind the scenes of the magazine since 2010. I’m thirty-nine this year (the photo of me, above, was taken in a yakisoba restaurant when I was thirty-six).

Some details of how I came to found the journal are mentioned in the interview I share below, so I won’t get into that here. What I will say to preface my breaking the fourth wall is this: After July 2011, I stopped signing the quarterly issues’ editor’s notes at least partly because, as the only full-time member at Asymptote, I didn’t want to overshadow the team’s collective efforts (for the same reason, I also declined to be videoed for our first-ever Indiegogo campaign). For several years thereafter, all editor’s notes were simply ascribed to “The Editors.”

In July 2016, I decided to sign my name after the editor’s note again: Prior to that, I’d seen Asymptote being written off as a mere “platform” by a prominent translator, but specifically in the derogatory sense of “editor X used the platform Asymptote to do Y” (Y being a massive translation project, requiring coordination across the different roles), as if all I had done was create a free-for-all Facebook or Twitter-like interface for providers of world literature. That could not be further from the truth: there is someone leading the magazine (although hopefully not off a cliff!), someone with a vision to boot, not merely a loose collective of editors, contributing whatever they’d like to contribute.

Secondly, I’d started wondering if, by not putting myself out there a little more, I had become complicit in, let’s just say, a certain racial oppression. This year, after six years of editing the magazine, I was happy to be invited to my first London Book Fair panel (actually any event not organized by Asymptote, although, as its editor-in-chief, I have played varying roles toward making 34 world literature events happen in four continents), and I remain eternally grateful to the Translators’ Association of the Society of Authors in the UK for subsidizing my trip there (as I could not afford the flight ticket otherwise).

But, few know that, in 2014, about five years into helming the magazine, and surviving those five years by wearing many different hats to keep the journal going, an invitation was received by someone on the team to represent Asymptote at an international conference, with the offer to be flown in from wherever. The invitation was sent to a part-time White Assistant Managing Editor who’d been on board less than seven months, who actually lived further away from the conference than me, based on her current city at that time. I’d left the US many years ago to avoid being an invisibilized person of color, specifically in a literary environment (Junot Díaz and Ken Chen talk about this issue very eloquently), and suddenly there I was being overlooked again.

A Fractured Peace: Artist Schandra Singh speaks with designer Shaill Jhaveri

It is over-stimulating, heartbreaking and beautiful. It's like falling in love and having your heart broken every day.

Although considered one of the fastest-growing markets in the world, the Indian art market is still very much in its infancy. Painting dominates it. Artists are broadly divided into the “moderns”: the more mature “legacy” artists whom collectors feel more secure in buying, and the younger, more current “contemporary” artists, who push the boundaries of Indian art. There was not much of a market till the 1990s, when a more vibrant art scene emerged for established and younger artists alike. Since then, despite economic ups and downs, Indian artists and artists of Indian origin have been making their presence felt across the globe. And the world is paying attention, not just to India, but to artists from throughout South and Southeast Asia.

Growing up in India, I was initially attracted to the Indian portrait painters, especially the sumptuous portraits of a royal India, with the Maharajahs showing off their impossible jewels. Later, I was drawn to the more accessible colored photographs, hand colored over black-and-white prints, stiff but theatrical, with the textiles and jewels jumping off the images. There are the overwhelmingly opulent paintings of the 19th c. Raja Ravi Varma from the princely state of Travancore, who fused European academic art into Indian traditions. Then, there are the haunting self-portraits of a half-Indian, half-Hungarian Amrita Sher-Gil. Of the younger artists, the portraits by Surendran Nair, precursors to his more stylized flat narrative paintings, are so very powerful, as is the realism of Abir Karmakar. The digital portraits of Mahatma Gandhi by Aditya Pande push Indian portraiture into another arena entirely.

Today, a lot of the geographical and cultural boundaries have blurred. A young Pakistani artist Salman Toor lives between Lahore and New York City, and finds that he paints himself in a lot of the figures of his poetic canvases.

In Conversation with Lulu Norman and Ros Schwartz

Our editor-in-chief talks with the co-translators of Tahar Ben Jelloun's About My Mother

Lee Yew Leong: First of all, how would you classify this new book from Tahar Ben Jelloun? The story opens with an autobiographical narrator (Ben Jelloun himself) talking about his ailing mother, but then changes mode with italicized passages, where we get stories about his mother’s past recreated from her perspective.

Ros Schwartz: Do we have to classify it? I think there’s a problem with trying to categorize books by non-Western writers which often don’t follow a linear narrative arc according to traditional European classifications. I appreciate that doing so makes life easier for publishers—and is essential when entering books for prizes and applying for subsidies—and for booksellers, but my experience of translating Francophone writers such as Ben Jelloun and Dominique Eddé (Lebanese author who writes in French) is that their books defy categorisation. So while this book is strongly autobiographical, recounting the demise of Ben Jelloun’s mother, it also has a strong fictional element where he imagines what might be going on in his mother’s Alzheimer’s-raddled mind.

Lulu Norman: Yes and also into the past, when he imagines her life as a girl and what it must have been like for her in the Fez of the 1940s; there’s a more obviously ‘fictional’ feel in those passages. The narrator, who is called Tahar, pieces together the story of her life, constructing a narrative out of what he knows and what he imagines. Ben Jelloun calls the book a novel, in order I suppose to give himself the fullest leeway and perhaps avoid any ruction in life, since everyone’s memory is so subjective.

LYL: Could you share with our readers what went on behind the scenes of this project? How both of you got attached to this translation, for example? How did English PEN play a part in the materialization of the book, and how long did you take to complete the manuscript?

RS: This project is very dear to my heart. I’ve wanted to translate Ben Jelloun ever since I read L’enfant de sable in 1985. A couple of years ago I’d just finished translating Escape by Dominique Manotti for Gary Pulsifer at Arcadia and he mentioned that he’d just acquired Sur ma mère. Gary, this one’s for me, please. It’s funny because as a translator you can get typecast. Gary had me down as doing crime fiction. Anyway, he immediately said yes, and wrote to Tahar to make sure he was OK with my doing the translation. In the meantime, there was a radical change of management and direction at Arcadia, and the project was dropped. I was devastated and wrote to Anne-Solange Noble, rights director at Gallimard, to ask if I could seek another publisher. I took the book to Lynn Gaspard at Saqi who snapped it up. Sadly Gary passed away before the book was published, which is why we have dedicated our translation to him. READ MORE…

Weekly News Roundup, 27 May 2016: Scrabble Champs

This week's literary highlights from across the world

Happy Friday, Asymptote readers! Nearly a year ago, the Asymptote blog published an interview with book artist Katie Holten, who “translated books into trees” with her Broken Dimanche Press book, About Trees. Now that very same book is in its second printing—a feat that is seriously nothing to sniff at in independent, artist-book publishing! And famed translator-slash-friend-of-Asymptote-anniversaries Edith Grossman is featured in the Los Angeles Review of Books‘ “Multilingual Wordsmiths” series, in an interview by Liesl Schillinger. READ MORE…

In Conversation with Yumiko Tsumura

"...she values the translation of her poetry into English, as well as into other languages, to plant her poetry on the globe."

Yumiko Tsumura’s translations of poems by Kazuko Shiraishi, also known as “the Allen Ginsberg of Japan,” appeared in our Winter 2016 issue. Recently Tsumura corresponded via e-mail with Interview Features Editor Ryan Mihaly.

Your first book of translations of Kazuko Shiraishi’s poems dates back to 2002. When did you first meet Kazuko, and how did you begin working with her?

I met Kazuko Shiraishi on September 30, 2000 in Tokyo. My co-translator, Samuel Grolmes, my late husband, and I had been working on a translation of Ryuichi Tamura’s poetry, ever since he was the first guest to the International Writing Program (IWP) at the University of Iowa established by Paul Engle. I was working on my MFA in poetry and translation and Sam was an assistant director to Paul Engle, and we started translating Tamura’s poetry during his stay at the IWP.

Tamura’s “The World Without Words” was published [in] New Directions Annual 22. When our book Tamura Ryuichi Poems: 1946-1998 was published early September 2000, Shichosha, the publisher of modern poetry, held a symposium in Tokyo called “How to Surpass Tamura” on September 30, 2000. Kazuko Shiraishi was a great admirer of Tamura’s poetry and one of the panelists. During that meeting she came to ask Sam and me to translate her poetry. READ MORE…

Ask a Translator with Daniel Hahn

...Get a contract. Make sure it’s unambiguous. Make sure it’s comprehensive. Make sure you understand it.

Our literary translator on the street, award-winning writer and editor Daniel Hahn, is back with another installment of “Ask a Translator,” the monthly column responding to readers’ deepest questions about the day-to-day practice of literary translation. This time around, Asymptote reader Marius Surleac asked the following:

Have you experienced troubles with any publisher and if so, what’s your advice for a novice?

Have I ever experienced any troubles with a publisher? Yes!

(Finally, a nice, easy one to answer.)

Because honestly, I’ve published close to fifty books so far, with publishers of all kinds, in various countries, so it would be surprising if every experience had been equally, perfectly smooth. Yes, of course there’s trouble, sometimes. And that trouble, naturally, can take several forms.

Ilan Stavans is Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College and the publisher of Restless Books. His most recent translations are Mariano Azuela’s The Underdogs (Norton, 2015, with Anna More), and Lazarillo of Tormes (Norton, 2016). A recent conversation with him on translation, with Charles Hatfield, is “Silence Is Meaningful,” Buenos Aires Review, July 15, 2015.

What is the best translated book you’ve read recently?

I am in the middle of a strange yet fulfilling experiment: I am rereading Madame Bovary in various translations at once (Eleanor Marx-Aveling, Geoffrey Wall, Lydia Davis, Adam Thorpe), along with the French original and a Spanish translation. I first read Flaubert’s novel in my teens, while still in Mexico. Coming back to it in all these dress-ups is, at times, an embarrassment of riches. Marx-Aveling was the daughter of Karl Marx. Wall wrote a biography of Flaubert. Davis is Davis. And Thorpe talks about the task as “the Everest of translation.” Unfortunately, the Spanish version (not the same one I encountered when young), in its title page, refers to the author as Gustavo Flaubert and to the novel as Madame Bovery. The rest, one might say, is indeed like climbing the Everest. READ MORE…

Interviewing Alexander Beecroft, author of An Ecology of World Literature

"The idea seems to be that globalization isn’t one simple story, but neither is it a collection of unrelated stories—it’s a tangle of narratives."

Alexander Beecroft is Associate Professor in Classics and Comparative Literature at the University of South Carolina. He teaches courses in Greek and Latin language and literature, ancient civilizations, both ancient and modern literary theory, and theories and practices of world literature. His key fields of research specialization focus on the literatures of Ancient Greece and Rome, and pre-Tang (before AD 600) Chinese literature, in addition to contemporary discussions regarding world literature. His second book, An Ecology of World Literature: From Antiquity to the Present Day, was published by Verso in January. In it, he argues for the benefits of an ecological, rather than the conventional economical, framework in the discussion of global literatures, shedding light on the difficulties involved in ascertaining, defining, and assimilating multifarious linguistic forms.

I spoke to Professor Beecroft through email about the intersections between world literature, politics, geography, and the advantages and disadvantages that literary translation can have on upholding minority languages.

Rosie Clarke: Could you begin by briefly outlining your academic background, and explaining what brought you to write An Ecology of World Literature?

AB: My earliest training, as an undergraduate, was in Classics, and from there I moved into an interest in early China. As I entered graduate school, I knew I wanted to combine those interests, but struggled for some time to figure out how. As I worked on my dissertation, I began to realize that, while many things about archaic and classical Greece and early (pre-220 BC) China were different, they did have an intriguing similarity. Both were politically fragmented regions within which circulated some sense of a shared culture. That first book explored that particular connection, but led me to think about how those kinds of structural similarities between literatures might be discussed in a more general way.

RC: Can you explain why you chose to structure the investigation here with an ecological framework?

AB: We’re very used to thinking about modes of cultural production, circulation, and exchange in terms of economic metaphors. Those metaphors have a real value: cultural recognition, like just about everything else, is in scarce supply, and so the language of markets and economic efficiency has much to teach us about culture.

I thought it might be helpful, however, to consider ecological models as an alternative. Ecology, like economics, deals in how scarce resources get distributed in a given context—but where economic models tend to suggest a single winner, and a single winning strategy, ecology suggests that there can be multiple strategies for surviving in different niches.

I think this is a particularly important point in today’s world. The power of English and of the English-language publishing industry worldwide makes translation, especially into English, into the most lucrative form of literary success—but in fact writers can and do thrive through other strategies, including by writing work designed for their own local context. Further, we need to recognize that the ecologies within which literatures operated in the past were different, operating for example under court patronage or with other kinds of relationships to the political and social order.

Best European Fiction 2016: A Conversation With Editor Nathaniel Davis

"There’s nothing great about a translation if the original’s no good."

The first volume of Best European Fiction, from the year 2010, brought together stories from 30 countries—introducing fiction by well-established writers such as Alasdair Gray and Jon Fosse in addition to stories by emerging European writers who had not yet been translated into English. Over the last six years, the series has published more than 200 stories from countries across Europe, from Iceland to Russia.

At a time when publishers are publishing dramatically less writing in translation, Dalkey Archive Press will release Best European Fiction 2016 on November 13. In an email interview, the volume’s editor, Nathaniel Davis, described the process of continuing to provide English-language readers with new artistic and intellectual windows that open out on to Europe.

***

MB: The call for submissions for Best European Fiction 2016 received more than 150 stories. Describe the process of whittling that number down to 29. What were your toughest editorial decisions? For example, were you conflicted in choosing between two authors from the same country?

ND: The way the selection process works, we choose one story from each country, and multiple stories for countries with more than one national language. So we might have both French and German stories from Switzerland, or French and Flemish stories from Belgium. Part of the project of Best European Fiction is to highlight writers from neglected linguistic traditions. So BEF2016 has Spanish stories written in Basque and Catalan, but not Castilian (although we often also include Castilian authors). After the primary selection of the best submissions, we have to whittle it down to about thirty, taking space and funding into consideration. We ask the participating countries to contribute some financial support to the anthology, as it’s a very expensive undertaking that doesn’t pay for itself (despite usually selling pretty well). READ MORE…

Issue Spotlight: Interviewing Uyghur Poetry Translator Joshua Freeman

"A lot of what's really vibrant and interesting in Uyghur poetry right now is happening primarily on the web, and even on phone messaging apps."

Your translation of Merdan Ehet’éli’s poem “Common Night” is Asymptote‘s first piece from the Uyghur. I want to point out two words from the poem: “pig iron” and “hellfruit.” Can you tell us about these words and how you translated them?

The Uyghur word choyun (also chöyün) refers to pig iron or cast iron, and for me it calls to mind something hard and rough. The connotations are much less positive than the words tömür (iron) and polat (steel), both of which are used in Uyghur personal names. In speaking of “a night poured into our spines like pig iron,” Merdan Ehet’éli may be alluding to Tahir Hamut’s well-known poem “Summer Is a Conspiracy,” in which Tahir refers to fear’s “pig iron voice”, which “seeps into the marrow / and hardens.” READ MORE…

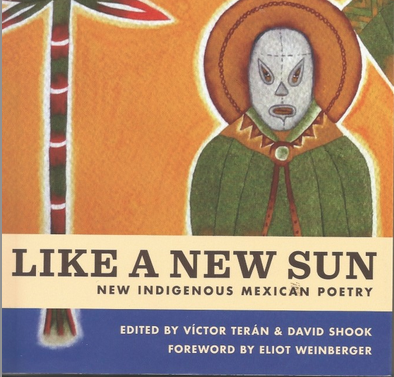

Translating Indigenous Mexican Writers: An Interview with Translator David Shook

"I suspect many casual bookstore readers might not know how many languages are still spoken in Mexico. The sheer diversity is astounding."

David Shook is a poet, translator, and filmmaker in Los Angeles, where he serves as Editorial Director of Phoneme Media, a non-profit publishing house that exclusively publishes literature in translation. Their newest book is Like a New Sun, a collection of contemporary indigenous Mexican poetry, which Shook co-edited along with Víctor Terán.

Seven translators in total—Shook, Adam W. Coon, Jonathan Harrington, Jerome Rothenberg, Clare Sullivan, Jacob Surpin, and Eliot Weinberger—translated poets from six different languages: Juan Gregorio Regino (from the Mazatec), Mikeas Sánchez (Zoque), Juan Hernández Ramírez (Huasteca Nahuatl), Enriqueta Lunez (Tsotsil), Víctor Terán (Isthmus Zapotec), and Briceida Cuevas Cob (Yucatec Maya). I corresponded with Shook over gchat to speak with him about the project.

***

Today is Columbus Day, a controversial holiday in the United States. Several cities have recently adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day over Columbus Day, clearly a victory for recognizing indigenous cultures in the United States. Which leaves me wondering: how are the indigenous Mexican writers recognized today in the Mexican literary landscape?

As someone who regularly visits Mexican literary festivals and also translates from the Spanish, I’ve observed the under-appreciation of indigenous writers firsthand. Mexico’s indigenous communities make up 10 to 14% of its total population, and you certainly don’t find anywhere near that percentage of literature being published in Mexico today. READ MORE…

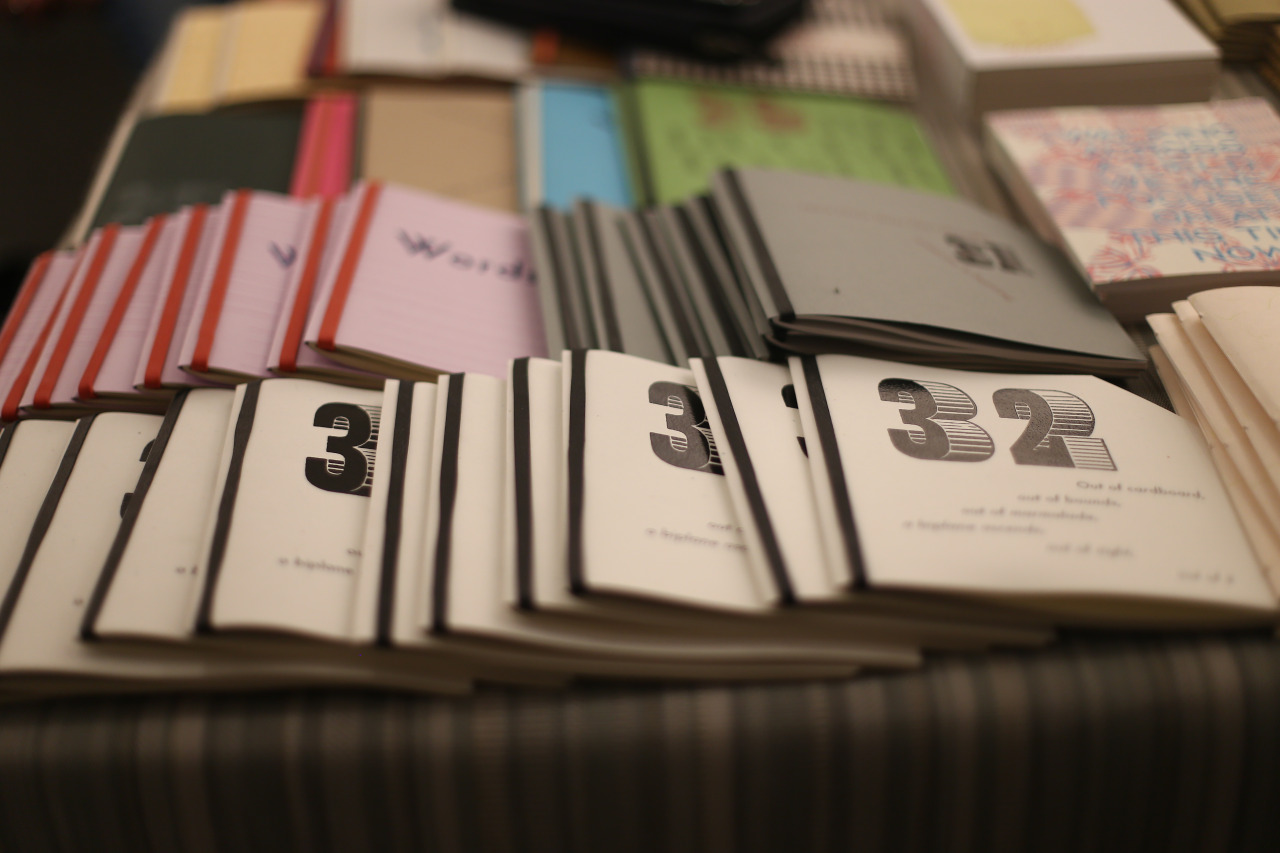

Publisher Profile: Ugly Duckling Presse

"I think there’s an interest among the editors in finding new translators, allowing the work of new translators to shine."

Ugly Duckling Presse is a nonprofit publisher for poetry, translation, experimental nonfiction, performance texts, and books by artists. Matvei Yankelevich is the co-founder and co-executive director of the press, and Rebekah Smith is an associate editor who spent the summer in Buenos Aires. We chatted over Skype about the press’s origins, as well as two of its translation series: EEPS (the Eastern European Poets Series) and Señal, which Rebekah and Matvei both curate.

Alexis Almeida (AA): I want to first ask about Ugly Duckling’s origins. I read recently that you started as a zine and over time evolved into a small press. Can you highlight a few major transformations that the press went through during in this time? What were you goals for the press initially, and how have they changed over the years, especially as you expand to include more collective members and publish new kinds of books?

Matvei Yankelevich (MY): Well, it’s important to say first that the press has very little to do with what the zine was, although the name stuck. When I moved to New York, I kept using the name for new collaborative projects with people I met. When we decided to actually do something more substantial, in the late 90s, we were just a group of writers, artists, and theater people. It wasn’t necessarily going to be a publishing house, but we decided to keep the name, Ugly Duckling Presse. What united us, or gave us the idea of working together, was that we were making books with each other, or for each other, so books were a common language. And the original idea was that we would publish things, maybe have a space, have performances and shows, but that was very difficult in late 90s New York. READ MORE…