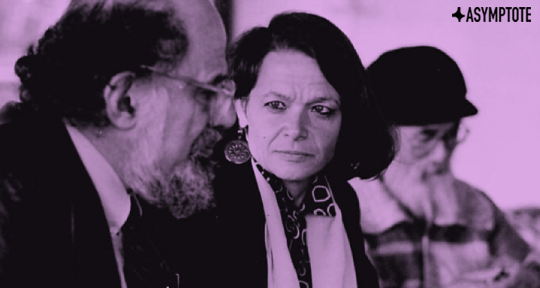

In this whirlwind and evocative interview, Asymptote contributor Alan Mendoza Sosa sits down with poet and professor Patrícia Lino to discuss just one of her many innovative approaches to poetry critique and response, the “infraleitura.” Based in expanded poetry, in which the word is not the ultimate form of expression, the “infraleitura” bypasses text to reach a visual, sonic, and tactile dialogue between poetic works as well as between poets. The “infraleitura” is ultimately a work of community; here, we are brought into the dialogue with a call to—in Lino’s words—“use it and transform it endlessly.”

Alan Mendoza Sosa (AMS): Could you tell our readers who are unfamiliar with expanded poetry what it is?

Patrícia Lino (PL): On the one hand, the association of the terms “poetry” and “expanded” is paradoxical. Poetry, since its beginnings, has always been expanded and has been linked to the idea of making something both corporally and intermedially. On the other hand, the association between “poetry” and “expanded” contradicts the logocentric and occidental tendency of modern poetry and reminds us, at the same time, of the importance and validity of the plural, unoriginal, and infinite qualities and possibilities of the poem, which, in addition to being verbal, can be visual, audiovisual, three-dimensional, performative, interactive, olfactory, gustative, or cinematographically conceived—as is the case for the poem in comics. In other words, the expanded poem is a composition contrary to the hierarchy of expressions, in which the word traditionally (and colonially) occupies the top, and image, sound, or gesture are relegated to, respectively, second, third, and fourth places.

AMS: You coined the term “infraleitura”; what does it mean and how does it relate to expanded poetry?

PL: The analytical tools of traditional literary criticism, which developed in the context of the aforementioned logocentric inclination, do not, by focusing primarily on the word, account for the various dimensions and materials of the expanded poem. The “infraleitura” arises, against interpretation, to respond to the absence of a bodily and decolonial way of reading poetry. It could be defined as an-impossible-to-define form of intermedial and creative essay, in which, as well as the poet’s body that expands to make the poem, the essayist’s body expands itself to understand. This other method of comprehension considers not only the word, but also any other useful means to grasp the poem in analysis. It is about reading with the whole body.