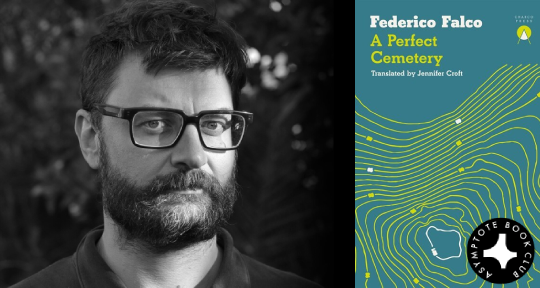

The vast contours of the internal landscape are painted with delicacy and precise restraint by Argentine writer Federico Falco in A Perfect Cemetery, our Book Club selection for the month of April. With his studies of life on the rural outskirts, the author gently but determinately probes the stoicism and stillness of human existence, and how a perceptible smallness and inwardness can betray a complex and considered philosophy of living. In light of our days being increasingly filled with aspirational stimuli, Falco’s work is a respite of care, of untangling the secret threads that connect the nature of being with the ways of the world.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive Book Club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom Q&As with the author and/or the translator of each title!

A Perfect Cemetery by Federico Falco, translated from the Spanish by Jennifer Croft, Charco Press, 2021

In five impeccably crafted short stories, Argentine writer Federico Falco displays his distinctive gift for distilling and dramatising the quietude of rurality to generate—from such ostensibly minor landscapes—an intense and varied portrait of life on the geographical periphery. Take, for example, the titular story: Víctor Bagiardelli, a scrupulous engineer of cemeteries, is commissioned by the mayor of small town Colonel Isabeta to build their first cemetery. Mayor Giraudo no longer wants to have the town’s dead sent to nearby Deheza to rest, but he meets resistance from the town council, who accuses him of abusing public funds in the interest of ensuring that his father is buried at home. “A bunch of ignoramuses who care nothing for progress,” Giraudo grumbles of a council whose inertness, he believes, only serves to secure the town in its provinciality.

Giraudo’s description—though unkind—is perhaps not an inaccurate assessment of Falco’s characters who, in their locality, shun the promise of progress. They are searching, instead, for a place to rest. Whether a literal burial place at the end of one’s life, or simply a spot to retreat to in order to go on living—the quest for silence and solitude constitute the central drama of their phlegmatic dispositions. After all, ‘cemetery’—from the Greek koimētḗrion—refers first and foremost to a sleeping chamber. A perfect cemetery, as the dark comedy of the collection’s title suggests, refers then to an ideal place for rest, recuperation, and languor. Read together, Falco’s fiction cohesively articulates—as the book’s intellectual and emotional pleasure—retreat as a way of life against the hedonism of pursuit.

Meanwhile, even as Mr Bagiardelli oversees the cemetery’s construction on the hillside down to the last weeping willow, and residents are eager to reserve the best spots for themselves—the 104-year-old Old Man Giraudo refuses to die, much to his son’s consternation and the engineer’s chagrin. Even the pinnacle spot in the cemetery, under the shadow of a majestic oak, is unable to convince the centenarian to rest reliably, as he actively plots against not just the cemetery’s but his life’s completion; as such, we come to understand how the ideal resting place never comes easy for these characters. That is, the only legitimate form of pursuit for the people who populate Falco’s landscape is one that is restlessly in search of stillness; a philosophy of solitude that knows how a privacy to live and die can be a hard-won thing. READ MORE…