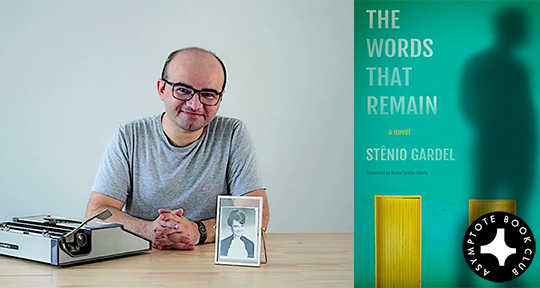

In Stênio Gardel’s The Words That Remain, everything hinges on the unfolding of a page. Through the Brazilian author’s vivid prose, a world unfurls between the covers: of unrequited love, of shame and survival, of rurality and history—all of it circulating a letter that its protagonist has never opened. Asymptote is proud to present this incredible debut work as our first Book Club selection of the year, a book that merges its triumphant celebration of language with the pivotal interrogation of marginalization, all along the long journey towards self-acceptance.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

The Words That Remain by Stênio Gardel, translated from the Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato, New Vessel Press, 2023

Much like the relationship that dominates it, The Words that Remain is just long enough to leave an indelible impression—but finishes in a flash. Stênio Gardel’s debut novel packs a literal and figurative punch, its brief pages flecked with contrasts: pleasure and pain, pride and shame, love and violence, peace and regret, strength and submission, what is spoken and what is kept silent. The storytelling moves fast, spanning half a century in its 150-odd pages, but Gardel’s sparse prose never creates a sense of freneticism. Through swirling reflections, the novel moves like a steady whirlwind, conveying inner turmoil and external inaction, punctuated by powerful, sometimes devastating change.

The Words that Remain tells the story of Raimundo Gaudêncio de Freitas, who paints his life as framed by two transformative events: learning to read and write at age seventy-one and falling in love at seventeen. Almost everything between the book’s covers oscillates between these two experiences, the chasm between them held taut by a letter—“half blessed, half cursed, wholly mysterious”—that he has never before been able to read. Penned by his past lover, the letter hangs over his life like a talisman, a burden, and a beacon of hope all in one.

Raimundo is gay. He and his lover, Cicero, are able to embrace their sexuality and one another for two years, but always with the fear of rejection from their families and community persisting in the background. This is rural Brazil in the 60s and 70s, and life is hard. Prevented from going to school by his father at an early age because “writing was for people who don’t need to put food on the table”, Raimundo must instead do backbreaking work to help support his family through floods, poverty, and infant death. While he longs for an education and the freedom to live with Cicero, the harsh realities of working-class life and widespread bigotry are so pervasive as to be almost completely internalised: being together gives them “a good taste, but [one] that left something sour in the back of their minds”, and even when they fantasize about living together, it is only imaginable in a big city—where no one will know they are more than just roommates. Sadly, their fears prove to be well grounded; when their families find out about their relationship, they are forbidden from seeing one another, and Raimundo is beaten mercilessly by his father for days, until he is driven away by his mother. In the long aftermath of this rejection, Raimundo thinks of himself as fated to wandering in a shadowy husk, his sexuality locked away, his life and love suspended in Cicero’s impenetrable letter, completely opaque like Cicero’s own destiny. READ MORE…