In Stênio Gardel’s The Words That Remain, everything hinges on the unfolding of a page. Through the Brazilian author’s vivid prose, a world unfurls between the covers: of unrequited love, of shame and survival, of rurality and history—all of it circulating a letter that its protagonist has never opened. Asymptote is proud to present this incredible debut work as our first Book Club selection of the year, a book that merges its triumphant celebration of language with the pivotal interrogation of marginalization, all along the long journey towards self-acceptance.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

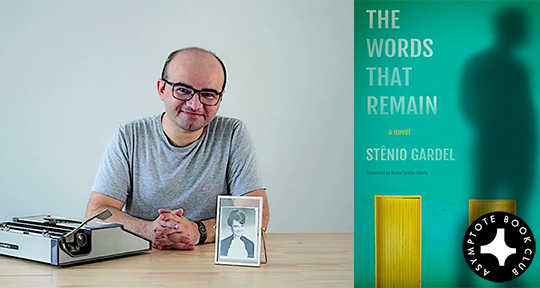

The Words That Remain by Stênio Gardel, translated from the Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato, New Vessel Press, 2023

Much like the relationship that dominates it, The Words that Remain is just long enough to leave an indelible impression—but finishes in a flash. Stênio Gardel’s debut novel packs a literal and figurative punch, its brief pages flecked with contrasts: pleasure and pain, pride and shame, love and violence, peace and regret, strength and submission, what is spoken and what is kept silent. The storytelling moves fast, spanning half a century in its 150-odd pages, but Gardel’s sparse prose never creates a sense of freneticism. Through swirling reflections, the novel moves like a steady whirlwind, conveying inner turmoil and external inaction, punctuated by powerful, sometimes devastating change.

The Words that Remain tells the story of Raimundo Gaudêncio de Freitas, who paints his life as framed by two transformative events: learning to read and write at age seventy-one and falling in love at seventeen. Almost everything between the book’s covers oscillates between these two experiences, the chasm between them held taut by a letter—“half blessed, half cursed, wholly mysterious”—that he has never before been able to read. Penned by his past lover, the letter hangs over his life like a talisman, a burden, and a beacon of hope all in one.

Raimundo is gay. He and his lover, Cicero, are able to embrace their sexuality and one another for two years, but always with the fear of rejection from their families and community persisting in the background. This is rural Brazil in the 60s and 70s, and life is hard. Prevented from going to school by his father at an early age because “writing was for people who don’t need to put food on the table”, Raimundo must instead do backbreaking work to help support his family through floods, poverty, and infant death. While he longs for an education and the freedom to live with Cicero, the harsh realities of working-class life and widespread bigotry are so pervasive as to be almost completely internalised: being together gives them “a good taste, but [one] that left something sour in the back of their minds”, and even when they fantasize about living together, it is only imaginable in a big city—where no one will know they are more than just roommates. Sadly, their fears prove to be well grounded; when their families find out about their relationship, they are forbidden from seeing one another, and Raimundo is beaten mercilessly by his father for days, until he is driven away by his mother. In the long aftermath of this rejection, Raimundo thinks of himself as fated to wandering in a shadowy husk, his sexuality locked away, his life and love suspended in Cicero’s impenetrable letter, completely opaque like Cicero’s own destiny.

For too long, Raimundo is trapped in a cycle of suppression, repression, and violence. Before leaving his home for the capital, Raimundo learns that an unmarked cross, under which he and Cicero often met, marks another family tragedy: it is the gravesite of his uncle, who, after trying to be open with his family about his homosexuality, was drowned by his own father—Raimundo’s grandfather. Although Raimundo’s father had once accepted and loved his brother for who he was, he is completely unable to talk about or acknowledge what happened beyond erecting an anonymous cross. Misreading the lesson he might have learned, he blames his brother’s death on his love for men, and perpetuates his father’s violence by trying to beat the same thing out of his own son. When that fails, he believes his son to be “just waiting for his [own] premature cross.” The cross that marks Raimundo’s uncle’s murder is not a crucifix, and his death is not figured as a sacrifice through which Raimundo might himself avoid suffering—it becomes seared in their memories as a brand of shame. It will take Raimundo a lifetime to learn what his father is never able to: that it is not his son’s and brother’s actions that are “filthy”, but his own.

When he moves to the city, Raimundo continues to be locked in the cycle of secrecy and violence inherited from his father; he pretends to be interested in girls, and drowns his as-yet inarticulable thoughts in manual labour. Even though he finds an employer who is also closeted, the only freedom this gives him is an introduction to “porn theaters”, which offer brief release but no relief. Raimundo keeps returning to them while pretending to be something he is not, and as such imagines them to be “full of sinners, full of disease and full of pus, by the body, the soul, we tried to drain our wounds there, one sucking the other, dirty like they said we were.” It is only when he meets someone who is “different, because she wasn’t ashamed”, that the long history of anguish begins to hint at a different future.

The necessity of casting off shame and regret, of rejecting violence instead of our identities, are crucial messages in The Words That Remain. While much social progress has been made, and while Brazil may be relatively open to sexual and gender diversity, it still reports one of the world’s highest LGBTQI+ murder rates. When Raimundo meets the transvestite Suzzanný, who will eventually help him make peace with himself, he is still internalising and projecting bigotry, violently marginalizing others just as society has marginalized him. But Suzzanný wears her difference loudly and defiantly, in spite of the peril it puts her in. Through her, Raimundo learns that the dissonance he feels within himself only exacerbates his distance from the rest of the world, and that the more he tries to repress and deny who he is, the more he hurts himself and those around him. Suzzanný also teaches him the necessity of living life openly, without the shadow of shame and regret—not that it will always be easy, not that there isn’t still work to be done, still words to be said, but that even at seventy-one, he can “find a new beginning”: as Suzzanný relates, “I let go of shame’s hand, I went one way, it went the other, and I walked away. I am still walking, to this day, sometimes limping a bit. But I am at peace with myself”.

The Words that Remain, through its very title, puts a huge emphasis on the value and power of language—on the ways that being able to read, write and articulate oneself can be utterly transformative. Gardel employs language and literary techniques in a deceptively simple method, cleverly rendered by Lobato into the kind of English one can imagine coming from the mind of an uneducated and illiterate—but not unimaginative—man. The prose pairs simple vocabulary with convention-defying syntax and grammar, self-reflexively talking about the power of words that “stretch and stretch our horizons”, and making extensive use of simple metaphors and simile to create a gentle sense of how “words [can] mean more than they seem.” Despite the experimentation, the novel never feels self-consciously highbrow, and the language reads as naturally in heightened displays of heat, anger, or passion, as it does in fragmentary recollections and hesitant thoughts. While I am generally not a fan of flashbacks, here the analepses come thick and fast, bleeding into and destabilising the present, making it feel less like reflective storytelling or a technique to create artificial suspense, and more like an image of a mind completely saturated with its past.

Gardel’s narrative style both embodies and replicates the experience of learning to structure one’s life and thoughts through text, of someone who “had it in him to get the words out, though they still got scrambled inside his brain, got caught in his throat.” Similarly, the novel confuses and obfuscates differences between real and imagined conversation, using free indirect discourse to show reported speech, a character berating themselves, or a longed-for exchange, until it is not clear what is really said and what only imagined. Here, the words that remain are both the ones left behind forever—through conversation, through writing—and those that might still one day be uttered, when we are ready and have learned how to say them.

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English and a senior copyeditor with Asymptote. She holds a master’s in translation and in 2016 won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme. Her first full-length non-fiction translation has recently been published with Scribe.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: