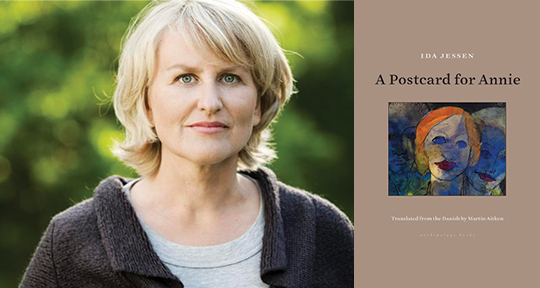

A Postcard for Annie by Ida Jessen, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken, Archipelago Books, 2022

Where did it come from, this hope of hers? From him. Her hope came from him. Without him she was shapeless. She would never be able to explain it to anyone, not even to herself.

A Postcard for Annie, Ida Jessen’s collection of short stories, opens with a woman named Tove, writing a note to her husband after an argument about herring; “I am not your fucking housewife,” she scribbles. Through the following six tales, Jessen tracks the inner lives of women, whose day-to-day lives in Denmark are as mundane and normal as they are dramatic and devastating. These stories explore what binds these women to the people in their lives against a backdrop as often comforting as it is bitterly harsh, putting into words what the characters themselves cannot.

From the outset of Tove’s anger, we sense that this is about much more than the raw fish fillets she had bought for dinner, and as she embarks on an “excursion” to put distance between her and her husband’s constant derision and judgment—which has rippled through her since the day they met—we become aware of the essential role he plays in her sense of self. Later, when a stranger spontaneously decides to sit at the table where she is dining alone, we quickly realise the approval and presence of this man are more important to Tove than her own discomfort. Without a member of the opposite sex there to notice her, Tove is “shapeless.”

As such, despite a loveless, bitter marriage in which only hostile words are exchanged, Tove never loses sight of her husband, and similar strictures and relationships weave a common thread through these stories. Tine, who feels “doomed at fifty to be a fire that can’t be put out,” doesn’t give up on trying to get her husband to go to bed with her. Ruth finds herself at the hospital visiting her estranged son, who even as a baby would “would squirm from her embrace,” and Lisbet, caught in an enmeshed mother and son relationship that is tense and taut after twenty years of push and pull, cannot—or will not—break free from Malthe:

He turns and strides away, exuding as ever his own will; he cannot tame it, it surges towards her, away from her. He is surrounded by a light so fierce that even a bitterly cold day in a dismal parking lot feels like unrequited love.

Honing in on these points of tension, Jessen carefully examines what these women experience, beyond traditional notions of female duty or obligation. They are stood up and lied to, given humiliating compliments, told not to ask questions, and encouraged to keep their opinions to themselves. Almost unbeknown to the outside world, these wives, partners, and mothers struggle under the weight of what Tove dubs “one thing after another.” At risk of being dragged under and losing her voice and identity in the process, she likens her condition to that of a listing vessel:

And when a ship takes in water, everything becomes gradually more unstable, the tipping point shifting alarmingly, until eventually all you can do is stand still and keep silent [. . .]

The tranquil landscapes and sleepy cityscapes of Denmark, which Jessen describes and Martin Aitken artfully translates, are often swathed in sheets of snow, a soothing balm to the various thorny encounters that take place. Lisbet, of the story “Mother and Son,” is a children’s swimming instructor; as she watches the winter sun shine on the trusting infants in their mothers’ arms, we are reminded of the unconditional trust that she, in turn, bestows on her son. Despite his bitter words and strikes, despite standing her up for lunch, there is an unwavering beam of light that will always bind her to him, and vice versa:

It’s the light inside the pool building. Even on a winter’s day, it makes them translucent. [. . .] It isn’t sharp, and it doesn’t glimmer. It doesn’t swell, doesn’t fade. It is constant, waxen, almost transparently white.

Tine’s story, “December is the Cruelest Month,” also traces the entanglement between mothers and sons. Caught between her duty towards her son, Mogens, and her growing suspicions that he was involved in the murder of a young mother, Tine sits beside his hospital bed and wonders: “This overgrown child of [mine]. When will he release his grip on [me]?” While Tine understands her son’s demise as a sign of her failure as a mother, her husband sees it as simply a woman’s problem to solve: “If only he’d have found himself a girlfriend. Maybe she’d have sorted him out.” It is in fact their daughter Gunhild who is then sent to alleviate her parent’s guilt and clean up her brother’s mess, and she is the one who goes to care for Marianne and Hanne, the two girls left motherless after the attack on that fateful midwinter evening.

Caught in these quiet inner conflicts, Jessen’s women seek solace in places and relationships they can call their own: Marianne dreams of her mother’s caress and treasures her new diary, which comes with a lock and key; Tine has her stable passion of translation, and Tove her upholstery business and best friend Larna. Yet even these apparent places of refuge can turn hostile or inaccessible, unfairly snatched from their grasp by the cruel hands of fate.

The titular story centres around the young student Mie, who—as she leaves her parents’ home and moves in with Annie and Bodil—finds herself caught in a sort of limbo between girlhood and womanhood. On the cusp of leaving the former and joining the latter, she is “consumed by the feeling that somewhere, one day, there would be a place for her.” As she searches amidst this state of uncertainty, she finds Ove. What is perhaps clear to the reader after the pair’s bristly first encounter is not so obvious to ingenuous Mie, and, ignoring all the signs, she runs headfirst into his arms, in an embrace that conceals everything that is to come.

Perhaps the most self-reflective of the collection, when Mie returns to her university town some twenty years later, it is she who comes closest to forgiving herself for not having known how things would turn out (what happened exactly with Ove, she doesn’t reveal), and for having almost lost herself along the way; as she tenderly revisits the memories of a young girl with “bone-hard cynicism”—a shell that stopped her from letting others in, or even from getting to know herself—it appears to dawn on her that what she had been searching for all along was actually with her roommates in that Aarhus attic flat. “I wasn’t as alone as I thought,” she muses.

It is with the custom delicacy, grace, and poetic efficiency that Martin Aitken has approached Ida Jessen’s prose, deftly capturing in English this quiet celebration of female connection, which is also a gentle mourning for what could have been, what never was, and what is. A Postcard for Annie is a collection of stories in which hope is masked in grief, regret, and yearning—yet found anew in nature, in friendship, and in time.

Rachael Pennington, originally from the north of England, is a translator and writer based in Barcelona. She volunteered as an Assistant Managing Editor for Asymptote from 2018–20 and has translated for Latin American Literature Today. Her poems and short stories have been seen in Loud Coffee Press, Parentheses, The Broken Spine and The Madrigal.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: