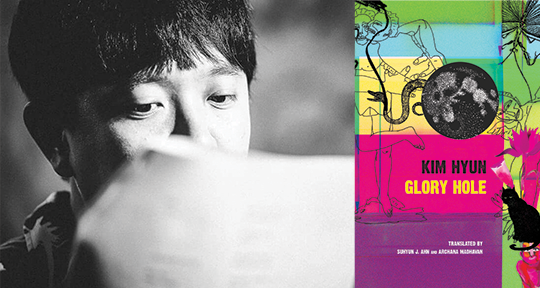

Glory Hole by Kim Hyun, translated from the Korean by Suhyun J. Ahn and Archana Madhavan, Seagull Books, June 2022.

Twentieth-century queer American visual artist Keith Haring was renowned for his pop art that emerged, according to critic Barry Blinderman, from the New York City graffiti subculture of the 1980s. His work predominantly engaged in queer activism, urging for safe sex practices and AIDS awareness. The poet Kim Hyun cites his 1980 drawing, Glory Hole—also the title of his own collection—in the notes to the poem, “Old Baby Homo.” The drawing shows a standing man with his head out of the frame. Two vertical lines represent the wall the man faces and where the eponymous glory hole is located. His penis is shown on the other side, burnished and luminous like the sun, surrounded by disembodied hands seeking it out. In an academic paper titled “Faceless sex: glory holes and sexual assemblages,” the researchers—Dave Holmes, Patrick O’Byrne, and Stuart J. Murray—posit: “[T]he glory hole affords an intense, temporary escape from the demands of subjectivity . . . The hole itself becomes the site of sexual energy and exchange.” Glory holes, by facilitating anonymous sexual encounters, enable a new politics of desire.

Arriving during the full-blown AIDS crisis in the US of the 80s, the drawing reframes queerness outside of the pathology of promiscuity, depravity, and disease. The glory hole, instead of being a vector for proliferation of the virus, is transformed into a fecund well of possibility. The paper further claims: “[D]ue to the fragmentation—the disorganization—of the body, the glory hole allows the free play of desire and fantasy for both users. Users may feel liberated not only from the social roles and expectations dictated by a predominantly heterosexual world, but also from the codes of the gay world . . .” Kim Hyun’s collection is not interested in being contained within any sort of category. From futuristic dystopias and planet hopping to alternate histories and forged references, from science fiction to pornography and literature to art, between prose and poetry, Glory Hole is unrepentantly queer in every way. The poems desist simplistic readings and are expansive in meaning, using language both in itself and as a vehicle to advance images that transform incoherence into the sublime.

The desire to evade external constraints reflects a queer aesthetic that breaks the bounds of the sexual and invades the textual. Whether it be the uncertainty of genre or the slippage between forms in poems that look, and often even read, as prose, Kim queers conventional “straight” understanding and skews the lens to look through the (glory) hole in the wall and discover a new orientation to the world. His transgressive style is paradoxically predicated on its unpredictability. As Park Sang Soo writes in his commentary, “The Real Queer Sci-fi-Metafiction Theater: A Handbook to Glory Hole,” at the end of the collection: “[Each] poem is like a Möbius strip, reflecting on itself endlessly, as would a hall of mirrors.” This feature obviously rises out of Kim’s location and subject. While South Korea does not criminalize same-sex relations—except in the military until very recently—it has no anti-discrimination protections, does not allow legal partnerships or marriage, and ostracizes openly queer individuals in a still conservative society.

In the brief translator’s note at the beginning, Suhyun J. Ahn writes: “Archana and I had to resist the constant urge to render these poems idiomatic, intelligible, and beautiful. Our goal was to emulate the discomfort Korean readers feel when they read Kim’s poetry.” The language works through gestures and whispers, the play of shadows and substitution. Meaning is layered in symbols that open up to inquiry. Take “Old Baby Homo,” which narrates a teenager giving a blow job to an unrequited crush. It is about growing old before time, becoming an adult while still a child: “Why have we, who were wiping Hometown ketchup with a napkin from Uncle’s Burger, aged so hastily?” The protagonist has been thrust into adulthood, not privy to the rules of this new world where the carefreeness of childhood finds no place.

The poem is tinged with melancholy and longing at life’s fleeting embrace: “Goodbye, for the sake of homos’ emotions who are at a glory hole with yellow buck teeth; who must be fleeing from purple summer in their crumpled soccer cleats.” Buck teeth is another image that immediately brings infancy to mind, a precocious joyous child forced to deal with their feelings and the sense of disgust or shame they arouse. The poem begins with a mention of purple rain signifying a sort of restlessness in being confined to identities and roles and of oncoming doom. It ends with the image of a purple summer, of ripening and growth, maturation, and senescence. The poem evokes how time marches on, claiming our lives and selves. It is impossible to escape its debilitating effects no matter how we try.

Park Sang Soo identifies a strand of the queer coming-of-age narrative—“two gay adolescents are transformed into the images of archangels Michael and Gabriel which appear directly or indirectly”—and links various poems across the collection. So poems such as “What Do Angels Do on Silent and Holy Nights” I-III, and “First of the Gang to Die” become slight variations on the same narrative “wherein two people in a homosexual relationship die in desolation after their paradise is lost.” Love results in pain, life is marred with tragedy, and joy is temporary. Yet, the momentary period of connection and bliss makes up for the loss. The angels and sequence of images in these poems thoroughly intertwine the transience of sex with the permanence of death. They collectively stand, according to Park, “for times of innocence, of being loved; for times of guiltlessly loving someone, and for distant times that you cannot return to; for times of violence and shame, and, at the same time, for memories that you can never shake off, for life that cannot fly off anywhere for broken wings.”

Another strand that threads these stories is the creation of sci-fi dystopias as the backdrop of action, littered with terminology native to the genre and commenting on a closely associated range of themes. He references known writers and works in a twisted way so that it becomes a game to figure out the homages. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the classic novel by Philip K. Dick, is recapitulated as Do Androids Dream of Cemeteries, a radio show hosted by an “electric girl” in “Greengrass Disappeared.” The poem “Sirius Somewhere” takes its cues from Sirius by Olaf Stapledon: the relationship between the super-intelligent dog, Sirius, and his human friend is altered into the relationship between the “I” figure and Sirius, the pet robot with a huge penis created by Tension Penis Corp, a company founded by Olaf Sky and Stapledon Wolf. Although there are not many poems explicitly sci-fi—“Galaxy Express 999,” “Nine Years on Jupiter,” and “A Tribute to a Replicant About Which Gary Mumbled”—most adopt elements like time travel, alternate planets, and robotics.

In this aspect, Kim Hyun’s work bears much resemblance to the stories of Kim Bo-Young, as they both ask: What are the limits of the human? Clones and robots mimic humanity, but to what extent? What is the fascination with this fidelity and when does it become inhuman? The multitude of cyborgs in Glory Hole speaks, once again, to the difference that characterizes queer lives and realities, their deviation from the norm. Park Sang Soo reads the book as “an oddly sad, bizarrely entertaining sci-fi epic narrating the journey of a cyborg born different from humans; who wanders the universe to explore his identity and eventually returns to a devastated Earth to greet death.” Soo expresses the cyborg’s yearning towards the human ideal, represented by the cis-het patriarchal centre, but as Kim Hyun will have us know, this yearning is misplaced and this mirroring of the Adamic existential impulse from Paradise Lost is a natural result of the defamiliarization common to queer lives. So the end goal is not to emulate the violent centre but to destabilize it completely and tear it down.

Annotations are crucial to the text and each poem has at least a few notes. Park declares the purpose of Kim’s collection is to construct fictions. He writes: “Fake stories are created over and over again. Notes extend beyond their boundaries, encompassing fake notes, fake citations, or notes mixed with facts and lies.” Kim deliberately blurs the boundaries between fact and fiction, truth and lies, forcing readers to question every single thing. Poems such as “Susan Boreman’s Retirement Party” and “Lone Wood’s Retirement Party” reconstruct the lives of these titular characters, porn actors both. In “Blowjob,” titled after Andy Warhol’s short film, the artist, renowned for blowjobs, finds his future dead body as a child. Marilyn Monroe is a cross-dressing man in “What Do Angels Do on Silent and Holy Nights; Duane and Michals . . .”, while James Franco runs into Hector in “First of the Gang to Die,” titled after a Morrissey song about a gang member named Hector. “Regarding Cate Blanchett’s Dream” is like a surreal cento drawing on her actual filmography. For Park, “there is no familiar reality, but [the one] we have imagined through curiosity.” Kim’s “I” speaker figure assumes many identities, often coterminous with the subjects of these poems, forming a hall of mirrors. It becomes impossible to distinguish between the real and the fake. The identities dissolve into each other.

In the translator’s note, Suhyun J. Ahn describes the dilemma of translating this collection. He writes that “[Kim’s] poems are not graceful. Nor do they incite vivid imagery. He hoards real and fictive references, distorts them, and plays with the violent incoherence that emerges from them. Notes are provided but only to disorient the reader further. However, this shattering of the sensible world is where Kim’s aesthetics lie. It is where queer people in South Korea live and persist.” These qualities open up the pieces to a diverse range of readings. Ultimately, the poems are paeans to a lived and visceral queerness that fluidly transcends hollow aesthetics of sterile craft and attempts to embody life in all of its glory. These songs celebrate both queer rights and queer wrongs, the beauty and the madness, the mess that undergirds everything. Glory Hole is frequently cryptic and impenetrable. It can be a chore to read and decipher. But Kim Hyun does not strive for comprehension and clarity. He privileges subtextual disorientation, a generative bewilderment.

Areeb Ahmad just got done with a Master’s in English and is doing his best to enjoy a short academic break. He likes to write about the intersections of gender and sexuality across texts. He enjoys exploring how the personal and the political as well as form and content interact in art. He is a Books Editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of Areeb’s writing can be found on his bookstagram, a true labour of love. His reviews and essays have appeared in Mountain Ink, Gaysi, The Chakkar, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: