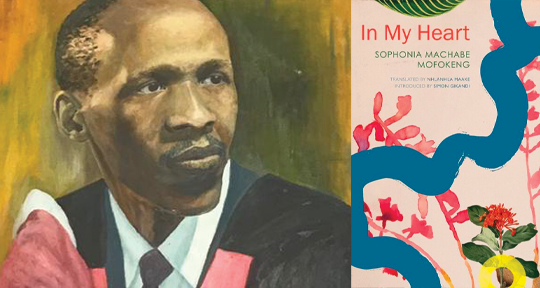

In My Heart by Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng, translated from the Sesotho by Nhlanhla Maake, Seagull Books, 2021

Despite an intent to explore beyond Anglocentric spaces, the framework of decolonial studies—defined as the analysis of dynamics between Anglocentrism and colonialism as well as of colonised populations—is still plagued with first-world privileges. Most decolonial texts are theorised and written by a dominantly white scholar community, within a hegemonic Euro-U.S. production. In fact, in the introduction to the original text of Pelong ya Ka (translated as “In My Heart”), Simon Gikandi quoted Karin Barber on how postcolonial criticism has failed to include texts written in African languages, “eliminating African-language expression from view.” By designating Anglocentrism as the form of knowledge production, academia defines what can be classified as “decolonial writing” based on an imperialist discipline of worth determination—comprising of research, praxis, theories, formulations, and discourses operating in materialistic space. To have decolonial texts navigate inter- and intrapersonal spaces is almost unheard of, and is unacknowledged as “real” decolonial scholarship in the Anglo academic sphere.

Sophonia Machabe Mofokeng’s In My Heart is a collection of meditative essays which enter and navigate these unheard-of spaces, introducing Sesotho worldview in radical decolonial studies. In this undertaking, he charts the territory of the heart, wherein the values and experiences largely considered universal—such as death and time—are interrogated instead as largely dominated by privilege. Gayatri Spivak introduces this book, the second publication of Seagull Books’ “Elsewhere Texts” series, as among the pivotal works of decolonial studies within their respective countries, essential in fighting “against a rest-of-the-world counter-essentialism.” She criticises the “global” efforts in bridging multiple cultures, however, through “the imperial languages, protected by a combination of sanctioned ignorance and superficial solidarities . . . even when they are at these global functions.”

In the first half of the twentieth century, Mofokeng was part of the new generation of Africans who had initiated a silent textual revolution against colonial institutions, which intended to control various African populations through “a regime of documentation.” Despite being part of the elite tutored population of Africans (as the first South African scholar to acquire a Ph.D. in Sesotho), his work operated outside of the authorised institution of the colonial university, and was written for non-elite readers in an attempt to engage with the African Being—not as a colonised subject or product of colonisation, but as a way of inhabiting the body.

These essays meditate on the matters of the heart—hence the title “Pelo,” which is Sesotho for “heart.” It includes a range of states, items, and experiences involved in the intrinsic transformations of life, identity, humanity, and spirituality; socio-economic and racial divisions are expressed through how different populations access and consume the material world of pleasure and beauty. For instance, in the essay “Horse Racing,” socio-economic differences can be distinguished from how one perceives beauty in the titular sport: the audience is divided by the outcome of their bets—which influences their opinions of the race. Instead of the joy and thrill he found in horse racing in childhood, Mofokeng as an adult encountered theft—the cause of a clear partition between happiness and loss. “We started realizing that there is plenty of sadness here,” he writes. “It took a long time for me to forget that.”

Although each essay focuses on a specific aspect of life—loneliness, friendship, the hospital, money—Mofokeng’s stream-of-thought writing embraces interdisciplinary thinking, allowing each specific aspect to interrogate its effect on other disciplines. Mofokeng taps into these topics in a delicate, passionate way that takes the hand of the reader, asking them to inhabit a Sesotho mind via lived experiences or events, to navigate the world through the eyes of a Sotho. This was particularly effective in showing how Sotho thinking applies intimately to contemporary life.

Temporality, experienced by spiritual and biological bodies, is a theme which threads most of these essays, particularly in “Time,” “Exams,” and “The River.” “Time” draws a comparison between imperialist and Sesotho perspectives of time—attitudes towards temporality which vary generationally due to socio-economic inequality. In contemporary thinking, time is often weighed in the expendable terms of capital production; few consider it a substance one can divide or spare for matters of the heart, such as acts of healing or care. Instead, the capitalist treatment of death, war, and debilitation has established a limit in the definition of time, wherein the human consciousness becomes attuned to each second as leading to a possible death—the moment time freezes. Thus, time is transformed into a source of pain and anxiety. In opposition, the Sesotho belief teaches that time should not be taught or learned as numbers that run out, but rather as a cure for pain.

“Exams” explores the capitalist system of timekeeping in education and learning by confronting the anxieties of a learner:

It is the fear that you may perhaps fail in your work, especially when you feel that you are weak at your work—and who would be so vain such that he feels that he knows his work? Even if he knows it, he starts by asking himself questions . . . will he pass the way he wishes? [. . .]

What was the purpose of studying if you are not given time to pour out for these examiners, so that they could see that your cup is full and overflows?

In the haunting question, “will he pass the way he wishes?,” the word “pass” can apply to the passing of an exam, the passing of life. The essay obscures the boundary between life and examination, coaxing us to think of both as essentially similar things. Mofokeng inquires, “Is life itself not work?” to initiate an interrogation into the systematic imperialism between the authorised institution and the student—a harmful amalgam of linguistic incapacitation, capital productivity, and biological debilitation. However, he also prompts us to recognise the dissimilarities between the structure and the individual, and the possibility of operating within these distinctions with compassion and care. Whereas a standarised exam commands a cold regurgitation of memorised information, life is an exam which tests one’s humanity, and to graduate is to be embraced by death.

Following “Exams,” the opening paragraph of “The River” made me think of how ecologies of violence and debilitation are systematically perpetuated to the point of normalcy.

When I opened my eyes, I already knew how to say, “Lesotho is on the other side of the Caledon River.” It is something that I knew so well, just like drinking water or eating. It was something that I was used to. And when you are used to something, my friend, it is not often that you think of it. You start thinking about it a lot only when it disappears or when you arrive where it does not exist.

In another paragraph, the essay shifts to an observation of borders, of the river as a neutral entity—a border which, unlike man-made signposts and property papers, practices equality. In his persistent descriptions of the river’s embodiment, relationality, and multi-scalarity in time, Mofokeng refuses to conceptualise the river as an exhaustive resource for extractive purposes, instead defining it as both a body that represents humanity in its fickleness and practice of care, and a timeless being in its testimony of history—as time itself.

In a detailed translator’s note that outlines his complicated and artful process, Nhanhla Maake writes that Mofokeng’s “meditative tone of voice, drawing on Sesotho wisdom, lore, symbolism, and figurative style, pose challenges that feel like a defiance and resistance of the primary text to be reduced to a secondary text.” Footnotes are required in order to contextualise the lore; most of it is deeply and subtly woven in the stories, whereas traditions in naming, certain proverbs and maxims, and religious imagery are described more directly. Some linguistic choices had to be compromised in translation, for instance the idiomatic expression “tselatshweu”—literally translating to “have a clear or white way”—was translated as “farewell.” Regardless, Maake’s translation skillfully tackles and negotiates these challenges, reincarnating the complex intercalations of Sotho cultural references and linguistic patterns in English.

Spiritual meditations and wisdom populate In My Heart. Its words capacitate the human imagination’s ability to dream of change—that it is material and intangible, and to understand that joy comes with enlightenment. The harmonic compromise of Sesotho and English, as well as the rich layers of radical imagining on both Mofokeng’s and Maake’s parts, has culminated in a vital work of human thought and passion.

Fairuza Hanun is a writer, an assistant editor of Asymptote Journal, co-founder of IWEC Indonesia, and co-editor in chief of youth- and POC-led GENCONTROLZ Magazine. Currently, she is a student in Foundation of Art and Education at the University of Nottingham.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: