A winner of Mexico’s prestigious Xavier Villaurrutia Award, Fabio Morábito’s El lector a domicilio is the first of his works to appear in English—and having read it, we can only hope there’s more to come. It’s hard to think of recent novels as well-rounded as this, which is why we’re delighted to announce it as our November Book Club pick: in just over two hundred pages, it delivers rich characters and riveting plots; it balances heart with humor; it sets us up only to shake our assumptions. More importantly, though, it finds value in lives that are often neglected, prompting us to fully see, hear, and touch those around us—an especially timely reminder as we continue to emerge from our pandemic solitudes.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

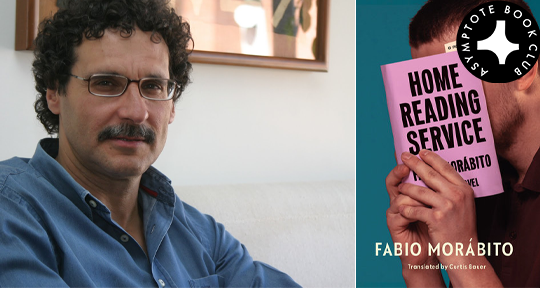

Home Reading Service by Fabio Morábito, translated from the Spanish by Curtis Bauer, Other Press, 2021

If ever a novel was deviously set up for stasis, it’s Fabio Morábito’s latest. Its protagonist, thirty-four-year-old Eduardo Valverde, is “stuck in second gear” after a case of reckless driving costs him his license, part of his job, and much of his time. Already living at home with an ailing father, he must now serve as a home reader to some of the other “elderly and infirm” in Cuernavaca—many of whom spend their days alone or half-silently with others, in dim rooms at the end of long passageways. Meanwhile, Eduardo has either cut or strained all ties with friends and family, and doesn’t seem keen on forming new ones; he, too, lives in “his own little world,” and while his court-mandated gig beats scrubbing public toilets, his heart just isn’t in it.

This is apparent to several of his listeners. “You come to our house,” one berates him, “sit on our sofa, open your briefcase, and with that magnificent voice of yours you read without understanding anything, as if we weren’t worthy of your attention.” To be fair, though, he’s not exactly dealing with a rapt audience. The Jiménez brothers are more eager to taunt him with vocal antics than take in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment; the Vigils lose focus on Verne’s The Mysterious Island when they can’t read his lips (they appear to be deaf), and they don’t bother to mention it until he brings it up; Coronel Atarriaga drifts off like clockwork after two or three pages of Buzzati’s The Tartar Steppe.

The characters’ mix of decrepitude, distance, and detachment sprouts from their broader environment. Once worthy of its nickname as the “City of Eternal Spring,” Cuernavaca has long since been “expelling young people and keeping only the old-timers around, like any godforsaken town of emigrants”—even “the bougainvillea on the fences are rotting.” The remaining population lives “closed up in houses and yards surrounded by high walls,” and these walls have “infected” them: “everyone walk[s] around stone-faced.” It is the product of “unchecked danger” at the hands of drug lords and mobsters, one of whom routinely visits the Valverde furniture store to collect a “protection fee.” But even this rattling occurrence is mentioned almost in passing, thus avoiding the immediate strike of conflict. The novel’s context in its first few dozen pages, then, seems hardly ripe for character or plot development.

Leave it to Morábito to shake our expectations and deliver both; after Eduardo discovers some of the late Mexican poet Isabel Fraire’s verses in one of his father’s old notebooks, the story begins to shift gears. The verses are worth quoting in full:

Your skin, like sheets of sand, and sheets of water swirling

your skin, with its louring mandolin brilliance

your skin, where my skin arrives as if coming home

and lights a silenced lamp

your skin, that nourishes my eyes

and wears my name like a new dress

your skin a mirror where my skin recognizes me

and my lost hand comes back from my childhood and reaches

this present moment and greets me

your skin, where at last

I am with myself

Whatever the poem’s inherent value (I, for one, am a sucker for synesthesia), it is especially affecting given its ties to the protagonist—through affinity, yes, but also through contrast. At the level of form, Eduardo is “strangely free to immerse [him]self in the whimsical typography of Isabel Fraire’s [broken] lines” because her poetry, like his life since the accident, is “something whole made up of fragments that [a]re waiting for an opportunity to come together again.” At the level of content, though, the poem doesn’t grant him such a comforting analogy.

It manifestly deals with skin, that most sensual of organs; with the love it engenders through sight (the lover’s skin is a louring brilliance, a mirror, a lamp, a visual feast), sound (as mandolin and silence), and most importantly, touch. But Eduardo isn’t privy to these pleasures in real life. Both emotionally and physically aloof, he seems incapable of touching others in either sense of the word. This double deficit is, perhaps, best portrayed in a stunningly raw scene that also features his father and sister:

One day, . . . [my father] had to take a shit and we needed to get him out of the car and find a secluded place among the trees. Holding on to me and Ofelia, he squatted and pushed in vain and ended up insulting us, accusing us of not knowing how to help him. He was right, neither of us were any good at that kind of thing . . . [F]inding himself entrusted to such clumsy hands, [he] decided to take matters into his own . . . [H]e began to treat us from then on with a subtle, almost smiling indifference.

Eduardo and Ofelia’s clumsy touch betrays an absence of tact (there is, revealingly, a single word in Spanish for the two); they are unable to connect with their father on physical terms, and therefore also on emotional ones. Granted, the old man is partly to blame. As a furniture seller, he’s always been careful that the merchandise “didn’t hit a wall or collide with another piece . . . That’s what his life had been like, taking care of things so they could pass from hand to hand, without becoming too attached to them.” That “spirit of detachment,” it seems, has been passed down to his children—most notably, his son.

If Eduardo lacks the sense and sensibility extolled in Fraire’s poem, his father’s live-in caregiver has them in spades:

Celeste scrubbed Papá’s clothes when they were covered with urine and sometimes something worse, with that squish-squash, squish-squash that had become a permanent sound in the house. She’d been taking care of him for three years, cleaning him, getting him out of bed and putting him back, handling his most intimate parts, where I’m sure my mother had never gone, and I wondered if out of that other squish-squash something like infatuation couldn’t emerge.

As in Fraire’s poem, skin and touch (“that other squish-squash”) are inextricably linked to love and care between the old man and his nurse. The more Eduardo watches them, the more he understands. When he fails to see Celeste’s beauty “through [his] father’s eyes,” for instance, he realizes he could only ever judge her through his father’s skin: “she’d touched him countless times,” after all, and “her hands must have been the only thing he looked forward to when he woke up every day.”

Celeste’s tactile, tactful nature extends to others, including a banker, a cab driver, and even Colonel Atarriaga, who becomes smitten with her because “she’s not hot and she’s not young, but she gives a really good massage.” Her interactions with the old and the ill—key among them, Eduardo’s father—lead the protagonist to a painful discovery: “I thought that Celeste and I shared that complicity which is so natural between the healthy who care for the ill. Now I realized that the real collusion was between the two of them behind my back. The real sick person in the house . . . was me.”

While Celeste forces him to recognize his shortcomings, home reading “client” Margó prompts him to overcome them. Moved by his rendition of Fraire’s poem, she insists on addressing him with the informal (and much more intimate) tú. He, too, unexpectedly warms up to her. The woman ten years his senior sitting across from him, wheelchair-bound, suddenly seems to him striking—almost as if the poem’s contents had seeped out of the page and onto her:

For the first time, the gloom the wheelchair imposed on her body parted and I had a glimpse of a desirable woman. Her laughter had disheveled her abundant black hair, usually tied back in a bun, giving her an aura of something between lascivious and unkempt that surprised me, and I asked if I could also use tú with her.

Margó also asks him to read Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel, in which the titular character seduces her younger cousin. “Mostly it was her skin,” reflects Eduardo, “incredibly soft, that bewitched poor Philip,” proof of “the overwhelming power a woman can possess with her body.” Once again, touch is hailed as an erotic force; when Margó later declares her love for our protagonist and kisses him on the cheek, he feels “her soft skin” and falls for her too.

This budding passion—and later, its loss—will spawn yet another epiphany: his ability to become engrossed in his own thoughts—losing sight of (and touch with) the plain and simple “prose of the world”—has never really been a sign of depth, but a form of evasion. He slowly learns how to feel “the skin of everything, the skin that is so close at hand and so elusive, so explicit and unobtainable.” The best way to be with himself—as Fraire, Celeste, and Margó have shown him—is to be with someone else; to touch them, skin and soul, as these women have touched him: “your skin, where at last / I am with myself.”

Morábito skillfully pairs this moving (and slow-moving) individual arc with a feverish collective story, whose twists and turns again relate to Fraire’s poem. After Eduardo shares it with the Reséndizes—a family who mask their own brand of inattention with theatrics—they decide to open up his readings to a wider audience. Soon after, others are invited to join in on his “performances.” What follows is a nightmarish comedy of manners, equal parts horror and humor, each serving to enhance the other. The humor in particular deserves a side note; it’s a deliciously smooth blend of irony and slapstick, cementing Morábito’s fame as a master of the genre. Translator Curtis Bauer does a brilliant job of conveying that mastery in English.

It’s rare for a novel to so deftly balance character and plot. It’s even rarer for a complex plot to sprout from such unlikely sources: the old, the ill, the poets. This, I think, is what makes Home Reading Service exceptional. On the one hand, its protagonist evolves through increasingly close contact with bodies past their prime; he is able to do so because Morábito paints them as bona fide subjects of love and lust—a far cry from our own take on aging and infirmity. Meanwhile, poetry is often relegated to the dark and dusty corners of our local bookstores—many think of it as idle exercise, free of any real-world implications. In the novel, though, it captivates the masses and drives them to a darkly epic climax. “Poetry can be dangerous,” says Colonel Atarriaga. Lucky for us, Morábito knows it.

Josefina Massot is a freelance writer, editor, and translator from Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied philosophy at Stanford University and worked for Cabinet Magazine and Lapham’s Quarterly in New York City, where she later served as a foreign correspondent for Argentine newspapers La Nueva and Perfil. She is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for the US, having previously contributed to the journal as an assistant managing editor and editor of the blog.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: