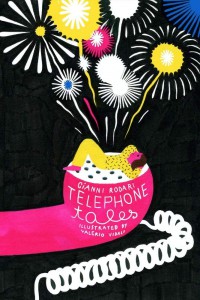

Before 2020 became the annus horribilis, fans of Italian children’s author Gianni Rodari had awaited it with excitement, as it marked the one hundredth anniversary of Rodari’s birth. Countless events and celebration had been planned, many of which still took place virtually, but perhaps even more interestingly, new editions and translations of and about Rodari’s work were issued. Among these is the first complete English translation of Favole al telefono (Telephone Tales), translated by Antony Shugaar and illustrated by Valerio Vidali for the independent children’s press Enchanted Lion Books.

Although Rodari is arguably the greatest Italian children’s author and his fame extends well beyond Italy’s borders, especially in the former Soviet Union, Rodari was never read much in the United States and Anglophone world in general, partly because of his ties with the Communist Party. Intrigued by their choice to publish Telephone Tales now, I had a Zoom conversation with Claudia Bedrick, the publisher, editor, and art director at Enchanted Lion. We began by discussing Rodari and ended up talking about children’s literature in translation more generally.

Anna Aresi: How and why did you decide to publish Telephone Tales now? Of course there was the anniversary, but Rodari was never famous in the United States. Do you think readers are more receptive now? The book has been a great success!

Claudia Bedrick: Yes, maybe. In fact, it was only coincidentally that it was published for the anniversary. We thought it would be published a lot sooner. The translator and I started talking about Telephone Tales seven years ago, but there were delays and it just happened that it was published last year (in 2020). My interest in Rodari stems from The Grammar of Fantasy, which exists in English, translated by Jack Zipes. That’s a book that I’ve known for a long time, a book that I’ve read and relied upon in the formation of Enchanted Lion. So when the translator contacted me about Rodari and Telephone Tales, I was already familiar with him, and I think this was a major difference between me as an editor and other editors he had spoken with. Like you said, a lot of people in the English-speaking world have no idea who Rodari is, even though he is arguably the greatest children’s writer of Italian culture, or one of them in any case.

AA: Thinking about elements of Telephone Tales that tie these stories to a very specific time and place I realize that, for example, when I read it with my children I sometimes feel the need to explain, to bring the work closer to them. Even if at an intellectual level I have specific ideas about reading to and with children, in practice I don’t always give them enough credit. As a parent, I often need to take a step back and let them deal with things. Children can do and understand more than we think they can, which is something they show us over and over again.

CB: Right, that’s true. That’s a large part of Rodari’s vision, his incredible respect for children, for the intelligence of children, and the absurdity of adults doing what you just described. It’s one thing to want to protect children from harm; obviously anyone, anywhere, should wish to protect children from harm. But this other mentality that somehow children aren’t up to the task of understanding the complication and the variety of human experience is a misbegotten notion.

AA: Enchanted Lion translates a lot and from many different languages and cultures. I think it’s an interesting position to be in within a market that, compared to others, doesn’t translate much and as a market that is often looked at as the place where interesting things happen (that is certainly the case of Italy, for example, which translates a lot and especially from American books). My perception is that in the United States there just isn’t as much interest or request for translated books as in other parts of the world. What are the challenges and the perks of doing the work that you do, bringing so much translated literature to this part of the world?

CB: Well, I guess one of the perks is our satisfaction and pleasure in it. I have a great team at Enchanted Lion and each of the people working with me has a distinct interest in translation, and each of them is bilingual or trilingual, so it’s also an unusual group for the US, because I think many people here are still monolingual, for however much bilingualism there is. We have a great shared interest in translation and we are aware of how much richness there is. And of course literature has always been a global literature, right? If you talk about the beginning of the novel with Don Quixote and you go forward. You have Dante, you have Homer . . . you talk about literature as something that crosses borders and boundaries and becomes a shared vision as to what life is and who we are as human beings, and so on. It’s a kind of artificial view to think of national literatures, that gets the mind going in the direction of fascism, when you think of a national literature, because it’s very artificial and it seems like it would be used to promote something ideologically. So, you know, we have a great satisfaction. It’s true that the landscape is a bit hard here because there’s not a real embrace of works in translation. I think that’s getting better and there is certainly more interest now than ten years ago in looking at books in translation and from all over the world. But there are certain biases and it’s really hard to get beyond them, that librarians and teachers and somehow people in the book community think that there is something difficult about a book in translation. That’s an irrational thought, because a book could not be complicated at all; it could be a very beautifully illustrated, very simple story that’s just bringing a lovely vision and experience to a young reader, and it comes from China, or it comes from Italy, or France, or Denmark or what have you, and there is nothing complicated about it at all. But people here still look at it like, “Oh, it’s a work in translation”—so there’s this kind of limitation. The way the whole market works, you know, the market needs a motor, and a big part of that motor is having authors and illustrators here who can travel, visit schools, visit bookstores, promote, share themselves, become very familiar names.

AA: It’s interesting. I think if you look at it from the perspective of children, for them a story is a story, it doesn’t matter. And then again it’s adults who bring all these other layers.

CB: Right, exactly. A child isn’t going to sit there and say, “This is a translation from Russian, nah, this is too complicated for me.” That’s nuts. That point of view is ridiculous. A story is a story, and everything in the world is new to a child. Absolutely everything is brand new, and they’re still experiencing a sense of mystery and strangeness, a sense of discovery and adventure every single day, so if you give them a book, it’s just more a part of that. But we as adults put things in boxes and categories in a different way.

Diversify Any Bookshelf with Three Children’s Books in Translation

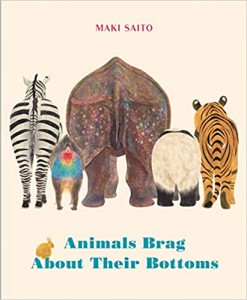

Animals Brag About Their Bottoms by Maki Saito, translated from the Japanese by Brian Bergstrom, Greystone Kids, 2020.

A lovely picture book for children ages three and up, Animals Brag About Their Bottoms offers a gallery of animals of all sizes, shapes, and colors from an “unusual” perspective.

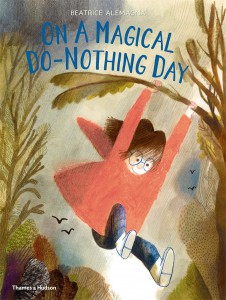

On a Magical Do-Nothing Day by Beatrice Alemagna, translated from the French by Jill Davis, HarperCollins, 2017.

A picture book for children four and up, On a Magical Do-Nothing Day follows the adventure of a boy who’s dragged to the country by his mother on a rainy day. A boring day of nothing transforms into whirlwind of excitement, adventure, and magic.

Telephone Tales by Gianni Rodari, illustrated by Valerio Vidali, translated from the Italian by Antony Shugaar, Enchanted Lion, 2020.

A collection of beautifully illustrated tales for children six and up, told by traveling salesman Signor Bianchi, who, every night, calls his daughter from a payphone from wherever he is in Italy. Each bedtime story can only last the time that a single coin can buy, but in this short time, incredible adventures unfold.

Anna Aresi is a U.S.-based Italian translator and educator. She is a Senior Copy Editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: