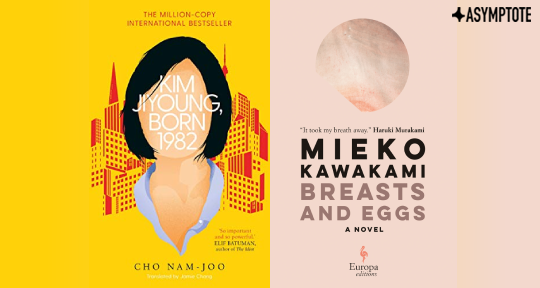

Two East Asian authors, whose debut English-language translations were published this year, have been hailed for their bestselling feminist works: South Korean author Cho Nam-Joo, whose novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 tells the story of a woman that gives up her career to become a stay-at-home-mother; and Japanese writer Mieko Kawakami, whose novella Breasts and Eggs recounts the lives of three women as they all confront oppressive mores in a patriarchal environment. Both works give voice to female protagonists and explore female identity in their respective societies. In this essay, Asymptote Editor-at-Large Darren Huang considers how both of these texts offer explicit critiques of male-dominated societies and argues that these authors are ultimately concerned with the development of female selfhood.

In Han Kang’s acclaimed 2007 South Korean novel, The Vegetarian, translated into English by Deborah Smith, Yeong-hye, a housewife who is described as completely unremarkable by her husband, refuses to eat meat after suffering recurring dreams of animal slaughter. Her abstention leads to erratic and disturbing behavior, including slitting her wrist after her father-in-law force-feeds her a piece of meat, and a severe physical and mental decline. She becomes more plant-like (refusing all nourishment except water and sunlight,) turns mute and immobile, and is eventually discovered soaking in the rain among trees in a nearby forest. Increasingly alienated from her family and society, she is committed to a remote mental hospital and supported only by her sister. Kang’s disturbing parable is characteristic of a number of South Korean feminist novels for its portrayal of a woman suffering from a form of psychosis that is incomprehensible to others, as well as its pitting of a protagonist against the oppressive mores of a rigid, patriarchal society.

Kang has disputed the characterization of her novel as a direct indictment of South Korean patriarchy and has preferred to focus on its themes of representing mental illness and the corruption of innocence. But two recent East Asian debut novels—Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by South Korean screenwriter-turned-novelist Cho Nam-Joo, translated by Jamie Chang, and Breasts and Eggs by the Japanese songwriter-turned-novelist Mieko Kawakami and adeptly translated into English by Sam Bett and Asymptote Editor-at-Large David Boyd—employ similarly oppressed middle-aged, female protagonists to form more explicit critiques of male-dominated, conformist societies. One of the defining qualities of both novels is that their protagonists attempt self-actualization by liberating themselves from traditional gender roles. These novels, which can both be characterized as bildungsroman, are ultimately concerned with a woman’s development of selfhood in opposition to societal conventions about motherhood and middle age. Both protagonists ask with yearning and desperation, what sort of woman can I be?

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, first published in 2016, became a literary sensation in South Korea during the country’s #MeToo movement and was subsequently celebrated by a number of women for its representation of institutionalized sexism and oppressive patriarchal norms. It recounts the life of Kim Jiyoung from birth until her present motherhood, when she starts displaying a form of psychosis, characterized by a trance in which she “truly, flawlessly, completely” transforms into other women by channeling their voices and personalities. Prior to her psychosis, Jiyoung had suffered rampant misogyny and the pressure to conform to societal expectations in each phase of her life. The narrative, which is written in distant third person by a detached narrator (eventually revealed as Jiyoung’s psychiatrist), is essentially a case study that catalogues the injustices in the mundane life of a millennial South Korean woman.

In Cho’s novel, oppression against women usually manifests itself as societal preference for men over women. As children, Jiyoung and her older sister receive crumbly tofu, dumplings, and patties after their younger brother is served the perfect pieces. As a teenager, Jiyoung is harassed by a classmate when she refuses his affections, and is then scolded by her father, who faults her for attracting attention by frequenting dangerous places and dressing lewdly. As an adult, when her in-laws and husband pressure her into having a child, it is Jiyoung, rather than her husband, who must give up her marketing career, which has brought her both joy and a sense of accomplishment, for childcare. Cho’s portrayal of South Korean society suggests a rigid hierarchy in which women are ranked below men in both public and private spheres. The biographical form of Cho’s novel—which is structured into sections of “childhood,” “adolescence,” and “marriage”—allows her to consider the constraining influence of a gender hierarchy on a woman at every stage of her life, from birth to motherhood. This ranking begins at the womb, when families, especially men and in-laws, strongly prefer sons over daughters, to the point of selecting sons by aborting females. Cho writes that during Jiyoung’s generation, “abortion due to medical problems had been legal for ten years at that point, and checking the sex of the fetus and aborting females was common practice, as if ‘daughter’ was a medical problem.” Therefore, a gender hierarchy begins to dictate the course of women’s lives even before birth. It can determine whether a girl will be given the opportunity to live or be extinguished in favor of a son. The strictures of such a hierarchical society are made explicit when Jiyoung’s sister is “erased” by her mother, who is pressed by her husband and in-laws to bear a son after two daughters. Girls are taught early that society attributes a superior value to men. When Jiyoung is caught eating her brother’s formula, her grandmother scolds her and gives a glare that Jiyoung interprets as, “How dare you try to take something that belongs to my precious grandson!” Jiyoung internalizes her grandmother’s preference and understands that she is less precious compared to her brother—that he and his things “were valuable and to be cherished; [her grandmother] wasn’t going to let just anybody touch them, and Jiyoung ranked below this ‘anybody.’” Repeatedly disenfranchised by a social order that reinforces male privilege, she realizes that the gender hierarchy commodifies boys and girls—she will always be seen as less precious goods.

Cho characterizes abortion as a form of erasure, metaphorically signaling the silencing of women and their invisibility in domestic and work life—both of which are among the defining symptoms of the novel’s diagnosis of its hierarchical society. When the adult Jiyoung, working at a marketing company, encounters a client company’s division head at a business dinner, such silencing is evident as he spews misogynistic remarks: backhanded compliments such as “You have a nice jawline and attractive nose—just get your eyelids done and you’re golden”; lewd humor, including “Once women pop, they can’t stop”; and he pressures her into drinking despite her insistence that she has passed her limit. The patriarchal norms of the workplace compel Jiyoung to remain silent and feign encouragement towards this misogynistic behavior, or risk losing her job. The scene speaks to the invisible systems based both in class and gender hierarchies that confer dominance to the male client and reduce Jiyoung to a state of invisibility. These systems are akin to those that perpetuate white male privilege in the US. The American poet-critic Claudia Rankine offers a parallel situation in Just Us, her hybrid exploration of race relations. She recalls a white man stepping in front of her in line for a flight and then belittling her after she protested. Rankine argues such racialized and gendered systems in American society have reduced her, as a black female, to invisibility or “lack of existence” and conferred privilege to white males. In Jiyoung’s workplace, women also suffer from a “lack of existence,” from being unseen, and from what Rankine calls “social death.” This deprivation is further suggested when Jiyoung’s team leader complains that the clients “want to treat us like servants one last time,” because servants must remain invisible and silent in deference to those they serve. Just as the American hierarchical system threatens to invalidate black voices, so Cho’s South Korean system of reality disempowers female voices.

Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs—first published in Japan as a novella in 2008, then later expanded and published in English in 2020—is similarly concerned with the liberation of women from patriarchal restrictions. This novel’s protagonist, Natsuko Natsume, is a thirty-year-old struggling writer living alone in Tokyo. The book is divided into two sections, with the second section taking place ten years after the first. In the first section, Natsuko is visited by two relatives: her older sister, Makiko, a divorcee and hostess from their hometown of Osaka who is seeking breast augmentation in Tokyo; and Midoriko, her twelve-year-old niece, who refuses to speak because of anxieties related to growing up. By the second section, Natsuko has published a well-received first novel but is struggling with the second. Confronted with her fears of growing old alone and her yearning to have a child, she returns to Osaka to see her sister and niece after a long separation. What unites these two sections is the women’s self-alienation, resulting from the dissonance between societal conventions and their conceptions of their own bodies, gender, and sexuality.

Throughout, the women experience their struggle through an alienation from their bodies. In the first section, Midoriko feels her body as foreign, as if she is “trapped inside [her] body.” She is especially concerned about her first menstruation because it will signify that she can become pregnant and have a child. However, unlike the stories she reads, which portray menstruation as something natural and miraculous, she sees her period as a source of distress and confusion, and she questions whether she is meant to become a mother in the first place. Precocious, introspective Midoriko asks in her diary,

Does blood coming out of your body make you a woman? A potential mother? What makes that so great anyway? Does anyone really believe that? Just because they make us read these stupid books doesn’t make it true. I hate it so much.

Midoriko’s bodily discomfort doesn’t just result from unpredictable pubertal changes, but also from her unease with societal expectations of adult women to bear children and become mothers. Natsuko is similarly alienated from the female body in the second section when she feels disgusted by sex with her first and only lover—and then with all men in general. This estrangement from the body also occurs when she cannot reconcile her own body with the idealized images of women’s bodies that she has internalized since childhood. She admits, “I guess I could say that I expected my body would have some sort of value. I thought all women grew up to have that kind of body, but that’s not how things played out.” Like Midoriko, Natsuko feels the foreignness of her body when her period occurs irregularly and she bleeds onto blankets shared with her sister and niece. Her irregular menstruation, alienation from societal images of women, and lack of libido result in a sense of entrapment by her own body, which cyclically recurs in Midoriko’s generation. Both Natsuko and Midoriko lose bodily autonomy when their bodies are subjected to constraining societal norms.

Both Midoriko and Natsuko’s dissociation from their bodies also reflect estranged relationships with their gender. Natsuko, in particular, feels a loss of identity as a woman because of her asexuality. She wonders whether she can be called a woman if she does not feel sexual desire for men like most of her friends, who enjoy sex multiple times a day. She admits to asking herself, “Am I really a woman? Like I said, I have the body of a woman . . . But do I have the mind of a woman? Do I feel like a woman?” She struggles with the normative prescriptions of her gender, which function as a form of control over women’s lives. Her struggle with gender norms is manifested by her concerns over whether she can continue a romantic relationship with Aizawa, the child of a sperm donor and a natural mother, whom Natsuko meets when she considers bearing a child through artificial insemination. When he confesses his affections for her, she responds, despite her own feelings for him, “I don’t have the right to be part of your life in that way . . . I can’t do normal things.” Later on, she challenges gender norms when she asks, “Why did caring about someone need to involve using your body?” Natsuko wants to break free from traditional gender norms but feels their suffocating presence in everyday life.

The novel’s role of gender recalls its characterization in the curator-theorist Legacy Russell’s powerful feminist manifesto, Glitch Feminism. Russell defines gender as the “invisibility that becomes seemingly organic,” and describes it as a “normative ordinary,” which suggests a “natural order in lieu of a most unnatural system of control.” Russell emphasizes the omnipresence of gender’s system of regulation: “In asserting itself as part of a vast normative ordinary, gender embeds itself within what we see and experience in the everyday, winding itself through public networks and spaces that we live in.” Natsuko struggles to define her womanhood on her own terms in a society that perpetuates gender as Russell’s omnipresent “system of control.” In this way, gender in Kawakami’s novel functions similarly to Kim Jiyoung’s hierarchical system in its omnipresence, entrenchment, and narrowing of women into conventional social roles.

For Natsuko, the most important consequence of this system of control is that it limits her viable routes to motherhood. Unlike Jiyoung who is skeptical of motherhood, Natsuko is seized by the desire to “know her child.” However, Natsuko has sworn off all heterosexual relationships because of her asexuality and therefore her only choice to bear a child is through artificial insemination. Japan has limited sperm donation to married couples and disallowed donation to unmarried women or to same-sex couples. There also exists a cultural stigma against donation, which is vocalized by both Makiko and Natsuko’s editor, Sengawa. Therefore, systemic societal norms, both institutional and those dictated by her gender, obstruct Natsuko’s route to motherhood and lead her to question whether there exists a place for her in a heteronormative society as a middle-aged asexual single mother. In this way, the second section extends the questions raised by Midoriko in the first over the role of motherhood in one’s identity as a woman.

One of the central concerns of both novels is this fraught relationship between motherhood and identity within societies policed by invisible systems of control over women. Both novels ask whether motherhood promotes or restricts women’s agency and their attainment of selfhood. In Kim Jiyoung, the protagonist’s identity is largely composed of her life as a career woman. She knows “the job did not pay well or make a big splash in society, nor did it make something one could see or touch, but it had brought her joy. It afforded her a sense of accomplishment when she completed tasks and climbed the ladder.” When Jiyoung gives up her career, she gives up an essential part of her identity. She feels motherhood has eclipsed all other elements of her womanhood: after she overhears office workers call her a “mom-roach” for not working, she protests to her husband, “My routine, my career, my dreams, my entire life, my self—I gave it all up to raise our child.” Ultimately, when Jiyoung forsakes her career, she suffers an erasure of part of her identity. Her psychosis, the expression of other selves, is arguably a reaction to this obliteration of her own self. The young Jiyoung was surprised her mother had dreams of becoming a schoolteacher because she thought “mothers could only be mothers.” The cruel irony is that the adult Jiyoung, oppressed by societal circumstances and despite her mother’s wishes otherwise, also gives up much of her identity for the sake of motherhood. Natsuko confronts a similar question between self and motherhood, between career and childbearing, when Sengaya dismisses her idea for having a child through sperm donation out of concern it will derail her from artistic achievement. Sengaya insists, “If you want to write, you have to make it your whole life . . . Great writers, men and women alike, never have kids. When you write, there’s no room in your life for that.” Sengaya frames motherhood as the form of erasure of self and ambition suffered by Jiyoung. However, Natsuko escapes this constrictive framework. Her eventual choice of motherhood by having Aizawa donate his sperm does not constitute a repression of self but a form of liberation—she has realized that an essential part of her identity is motherhood. Therefore, motherhood becomes a means of self-actualization, affirming a part of her identity that she was uncertain ought to have existed. For Natsuko, motherhood coexists peacefully with the other elements of her identity: by the end of the novel, she successfully completes her second novel, while starting to raise a baby girl. This positioning of motherhood is different from that of Kim Jiyoung, whose protagonist’s motherhood is basically forced upon her against her will by societal conventions and entirely consumes her identity. In Breasts and Eggs, motherhood becomes a form of agency, while it constrains and limits agency in Kim Jiyoung.

The level of agency in these two middle-aged female protagonists is one of the most significant differences between the two novels. Jiyoung is repressed by her hierarchical society from childhood and her path to womanhood is marked by the narrowing of her agency. Natsuko defies heteronormative societal norms by choosing a stigmatized route toward motherhood. This is a seemingly conventional endpoint but one which signifies an expansion of her agency because of her unique self-chosen familial arrangement and her recognition of motherhood as a form of self-affirmation. The specific narrative structures of the novels also reflect the agency of their protagonists. Jiyoung’s lack of agency is suggested in a narrative that is shown to be told not by Jiyoung herself but by her male psychiatrist. This man claims to now understand the plight of middle-aged women in society but is revealed as complicit in patriarchal norms when he ironically plans to discriminate against married women after one of his counselors quits to care for her child. Jiyoung’s lack of control over her own narrative is contrasted with Natsuko’s autonomy over her own, which is not only completely narrated in the first-person by the protagonist but suggested as possibly written by Natsuko herself when in a metafictional moment a fellow writer advises her to write about her unique path to motherhood. This is an example of Kawakami’s identification of writing and motherhood as not only acts of creation but of seizing one’s narrative from being overwritten by society, which tragically occurs for Jiyoung.

Though Natsuko negotiates societal norms towards a fulfilling form of womanhood on her own terms, these two novels are haunted by pessimism about the entrenchment of the invisible yet oppressive systems of control within their societies. This entrenchment is reflected both in women such as Makiko and Jiyoung who repeat the same oppressed lives as their mothers and gender politics in life beyond the novel, as evidenced by the large contingent of Korean anti-feminist men who denied the cruel reality presented in Kim Jiyoung after its publication. Still, the persistence of these patriarchal systems emphasizes the importance of feminist literature such as these two novels that create spaces for listening to women voices that have been traditionally silenced either through invisibility or marginalization. These two novels embody the ethos for women’s liberation put forward by the British historian Sheila Rowbotham in Women’s Liberation and the New Politics:

The revolutionary who is serious must listen very carefully to the people who are not heard and do not speak . . . Unless attention is paid to the nature of their silence there can be no transmission of either memory or possibility and the idea and practice of transformation can accordingly not exist.

Darren Huang is a Manhattan-based writer of fiction and criticism. His work has been published in Bookforum, Music and Literature, Gathering of the Tribes, Hong Kong Review of Books, and other publications. He is an editor at Full Stop and editor-at-large for Taiwan at Asymptote.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: