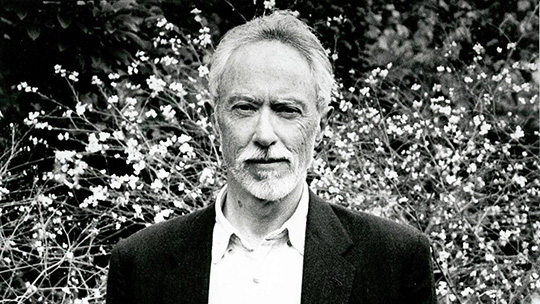

“Do maintain the colloquial tone,” David Colmer reminded me during a recent exchange about editing. And it was far from the first time I’d heard the Amsterdam-based Australian translator emphasize the importance of respecting and preserving the vernacular. Certainly, David’s almost chameleon-like ability to absorb and translate divergent Dutch and Flemish voices in fiction and poetry has led to his name becoming synonymous with Dutch-language literature in translation.

Over the past two decades, David Colmer has translated the work of celebrated novelists including Gerbrand Bakker, Dimitri Verhulst, and Peter Terrin; the poetry of Anna Enquist, Hugo Claus, Martinus Nijhoff; former Poet Laureates Ramsey Nasr and Ester Naomi Perquin; and the work of iconic Dutch children’s author, Annie M.G. Schmidt. Colmer has received numerous prizes, including the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for his translation of Gerbrand Bakker’s The Detour, The Vondel Prize for his translation of Dimitri Verhulst’s The Misfortunates, and the NSW Premier’s Prize and PEN trophy for his entire oeuvre.

In spite of his numerous achievements, David is most comfortable discussing his current projects and the challenges faced by translators at all stages of their career. For David, keeping it “colloquial” also seems to be code for not getting carried away, a timely reminder that the original voice and tone of any text should remain the translator’s constant anchor. With this in mind, I invoked the Dutch-peppered Australian we both speak, and asked David about his recently published translation of W.F. Hermans’s classic postwar novella, An Untouched House, the art of switching Englishes and his advice for up-and-coming translators.

March 2019

Sarah Timmer Harvey (STH): The last time we saw each other was at the end of 2018 when you were in New York for the publication of your translation of An Untouched House by Willem Frederik Hermans. An Untouched House is a dark, confronting, and occasionally absurd novella about the final months of the Second World War first published in the Netherlands is 1951. How did you come to translate it?

David Colmer (DC): I was the next cab off the rank, I suppose. I read the original in the early nineties soon after starting to learn Dutch, and it made quite an impression. I remember being shocked by the disturbing clarity of the author’s amoral vision and the climactic eruption of violence. The way he managed to combine a coolly thoughtful, almost philosophical perspective with both gripping action and humor was inspiring. I made a mental note of it as a book I’d love to translate, as I sometimes did after I began reading in foreign languages in the late eighties. Hans Fallada’s The Drinker was another one that made a similar impression on me, but I never really counted on the opportunity coming along. Over the following fifteen years, though, two things happened that changed that. I began to establish my credentials as a translator of Dutch literature, and Hermans had a late, second wave of publication in English, with two of his best novels, The Darkroom of Damocles and Beyond Sleep, published in translations by Ina Rilke and being very well received. Then, three or four years ago, when a Hermans story was slated for inclusion in The Penguin Book of Dutch Short Stories, Ina wasn’t available to translate it, so I was able to take up the baton.

READ MORE…