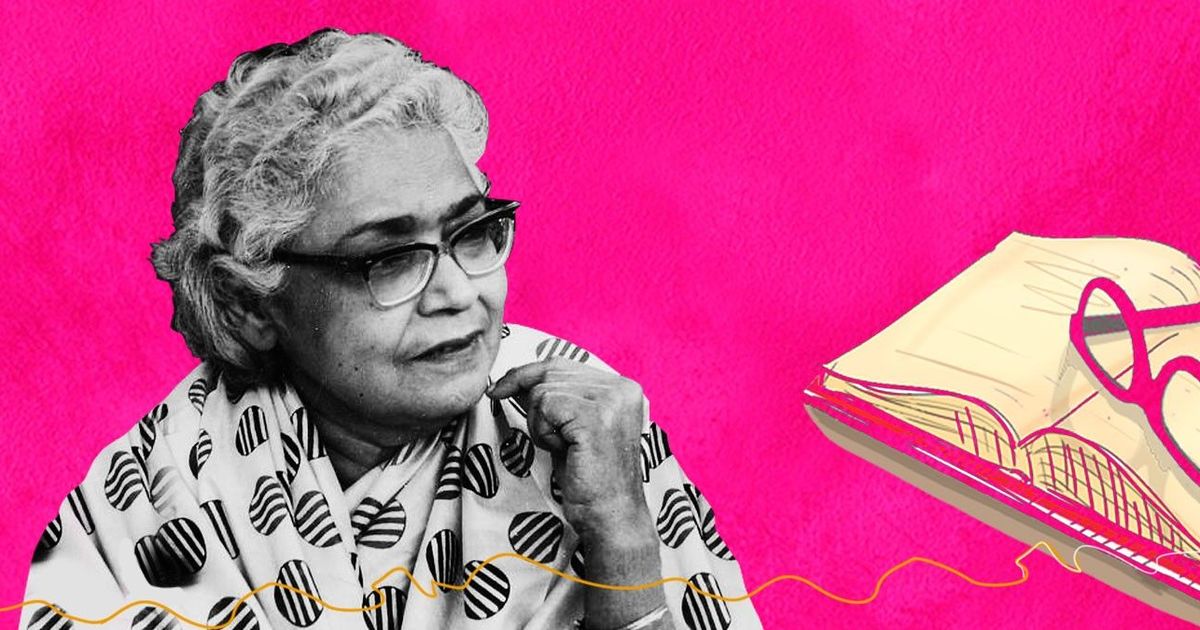

Twenty-six years after her death, Ismat Chughtai (1915-1991) is one of Urdu’s most famous short story writers; among her immediate contemporaries, only Saadat Hasan Manto’s reputation matches hers, and we can confidently say that she has no successor.

The Quilt, the first of her works to be presented to international audiences in the year of her death, was a collection of her short fiction. The title story, which had a lesbian theme, created a scandal and attracted the ire of colonial censors when it was first published in the early forties. Other stories in the volume proved the author to be a storyteller of the finest calibre. In 1995, more than half a century after its original debut, a translation of her magnificent feminist bildungsroman, The Crooked Line (1942), where the heroine’s life paralleled her own, pre-empted and fictionalised many of the ideas from Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Although it is still in print in the US with the pioneering Feminist Press, the UK edition has been discontinued. Several more translations of her stories, essays, memoirs, and long and short fiction, accompanied by a slew of biographical and critical studies, have enhanced her reputation year by year and made her one of the most translated writers across the subcontinent. However, they have only been published in India and Pakistan and have not been picked up by Anglo-American publishers.

Chughtai’s fiction ranges from stories for children and reminiscences of her friends and family, to the harrowing low life in Bombay’s slums and drug-fuelled high life in the city’s gaudy film world, to a novel about Islam’s first martyrs—a choice that surprises admirers of this iconic socialist-feminist icon. But even today some critics claim that The Quilt overshadows her other fictions and use the early stories to measure her later work. Others, including myself, would say this is grossly untrue: Ismat, though she preferred to write about what she knew best, was versatile within her chosen range of subversive kitchen sink drama and outspoken social satire, as we can see from the several renditions into English of all her major works by Tahira Naqvi, her most frequent translator, which are published in Delhi by the pioneering Women Unlimited (Penguin India also publishes a handful of translations by Mohammad Asaduddin).

Quit India, the latest volume from Naqvi and WU, foregrounds the sociohistorical aspect of Chughtai’s art. Published on the 70th anniversary of Independence and Partition, the stories here range over three decades and focus—often indirectly—on the events that led up to Partition and the decade that followed, without relinquishing the fierce egalitarianism and intimate detail of many of her most famous stories.

The earliest story, “Infidel,” narrated in a colloquial first-person voice, is about the childhood friendship of a Muslim girl and a Hindu boy that, when they grow up, leads to their civil marriage. In 1938, when the story appeared, such an event would have caused at the very least a ripple of protest in both communities. Intermarriages are an abiding metaphor—in this collection and in Chughtai’s fiction in general—for communal harmony and sectarian strife. Structured in short chapters, like a novella, the second story, “My Child,” though written only two years later, is technically far more complex. The Hindu-Muslim dyad is reversed here: Rashid, a Muslim writer, and Birju, a Hindu girl, are brought together by their affection for an orphan child of unknown provenance, whom they claim as their own; the light-footed but daring thematic movement here is not only the interreligious affair but the idea of an unmarried mother, even though the child isn’t really Birju’s. In the background, riots between communities unfold with a thudding regularity. Another civil union follows.

The title story, “Quit India,” written more than a decade later, begins with a poignant tableau: one-eyed William Eric Jackson, an Englishman, has just died; Sukhu Bai, his Indian mistress, and their mixed-race child are grieving on a Bombay street. The story flashes back to 1942 and the height of the eponymous movement. A first-person narrator one might identify with Chughtai herself (who often and elliptically uses this technique) recounts Jackson’s odyssey: “He was once the ‘citizen of a despotic nation, a man who soldered the chains of bondage…shot bullets into children who were my compatriots. Who had rained fire with his machine gun on unarmed people. … A cog in the machinery of the British Raj.’” But when his wife leaves with her children for England, he chooses to stay with his native mistress and their son. The narrator is angry with Sukhu Bai:

The bitch, she had decided to be the delicious morsel for the wicked dog that belonged to the white race. Was there a dearth of cripples and bastards in her own country so that she felt the need to auction off its honour? Every day Jackson got drunk and beat her up.

When Jackson returns from a mysterious absence after independence and allows his partner to support him by earning her living cleaning houses and weaving baskets, the curious narrator begins to question him about his past, yielding its own pain: illegitimacy and dispossession, the search for advancement in the colonial army, and eventual choice of mistress over wife and India over homeland. As he dies, he reflects:

Your country and your race are Sukhu Bai, who gave you refuge and love. Because she too is an outcaste in her own country, just like you. Just like the millions who are born in every corner of the world. Whose births are not celebrated with trumpets, and who are not mourned when they die.

The most recent of Chughtai’s fictions included here is a sophisticated mid-60s spin on the first story in the book, but there are stronger pieces in this selection. In my review for Asymptote of an earlier volume of Chughtai’s stories (2013), I remarked on the absence of a couple of signature pieces from the 60s: “Quit India” and “Roots,” both of which are included in this collection. The latter chronicles the last days of Partition and the decision of an elderly widow to let her family leave for Pakistan while she herself stays behind.

One of the most powerful pieces here, which also dates from the early 50s, is the genre-blurring “Fragile Threads,” which begins with a journalistic evocation of Gandhi’s birthday celebration:

But why this air of gloom that hovers over chawls . . . as though no one had been born on October 2, rather thousands had died and millions had turned to ashes? . . . It’s quite possible that his [Gandhi’s] name will even be used to spill blood in a third world war.

Chughtai shifts from documentary mode to a series of vignettes that depict, through several members of an unnamed narrator’s Muslim family, the economic and social psychology of post-national India. She was already aware of the rise in corruption and the growth of disharmony in communities, as this story, which combines the techniques of essay with those of the short story, reveals:

There are no police standing on guard on illegal alcohol . . . no guards on black markets . . . none on thieves and plunderers . . . on bribery and prostitution . . . Every conceivable filth is growing and blooming . . . but there’s a guard over those who seek peace. Death is strutting about bravely while a padlock is placed on life’s lips.

In the original Urdu, this story is an example of linguistic virtuosity: alternately dense, harsh, satirical, allusive and painterly. I’ve written elsewhere that while it’s possible to convey the structural strengths of Chughtai’s fiction, it would be a feat to capture her style in a foreign language. In this case, however, Tahira Naqvi makes a brave attempt at tackling Ismat Chughtai’s complex original. This varied and beautifully calibrated volume succeeds in sustaining the legacy of one of India’s most radical twentieth-century authors.

Aamer Hussein is a Contributing Editor at Asymptote. He was born in Karachi in 1955 and has lived in London since the 1970s. A graduate of SOAS, he has been publishing fiction and criticism since the mid-1980s. His works of fiction include the collections This Other Salt (1999), Insomnia (2007), and two novels, Another Gulmohar Tree (2009) and The Cloud Messenger (2011). He has edited an anthology of writing from Pakistan called Kahani (2005). He also regularly publishes fiction and essays in Urdu, his mother tongue. His most recent book of stories, 37 Bridges, was published in India by HarperCollins in 2015, and won the 2016 Embassy of France/Karachi Literature Festival Prize for Fiction.

Image credit to Scroll.in.

*****

Read more reviews: