A novelist and translator of Hebrew literature into Arabic, Nael ElToukhy’s passion for Hebrew literature is “rare,” by his own admission, among students of the language in Arab universities. He moves with dexterity between different registers of colloquial and standard Arabic and his speech is often loaded with profanities, at other times with creative coinages. Venturing beyond from the Statist logic that led to the creation of Hebrew departments, ElToukhy interrogates the semitic roots of Arabic and Hebrew, presenting his thoughts on the two languages as a novelist and translator; the challenges that two semitic languages present, the similarities in trilateral roots and the prejudices facing their readers on either side. He has published a collection of stories and 4 novels, the latest of which, The Women of Karantina (2014), is available in translation.

OA: In a series of articles you wrote, you say you first studied Hebrew in university because your marks weren’t good enough to study English. What dictated your direction when you first became a translator?

NT: At first you are in line with what they [the publishers] want, more than what you want. Because you need to justify your existence, to justify the language you use, and in addition to this, being a young man, you don’t usually know what you want, but this comes with time and you become interested in some things more than others.

OA: How did your interests develop?

NT: There are many stages in this; first I was interested in the Israeli left, the radical left who’s against the occupation and is anti-Zionist, and now there has emerged a more interesting topic for me which is Arab Jews or Jews who came from Arab countries, I work on both but now my passion has shifted to the second topic and to themes such as how Arab Jews learned Hebrew and how Hebrew mixes with the Arabic of their grandparents, and then comparing their dialects and accents to Ashkenazi Jews who came from Europe. This gradually became more interesting than the radical Israeli left.

OA: How does this affect your translation process and your choice of texts?

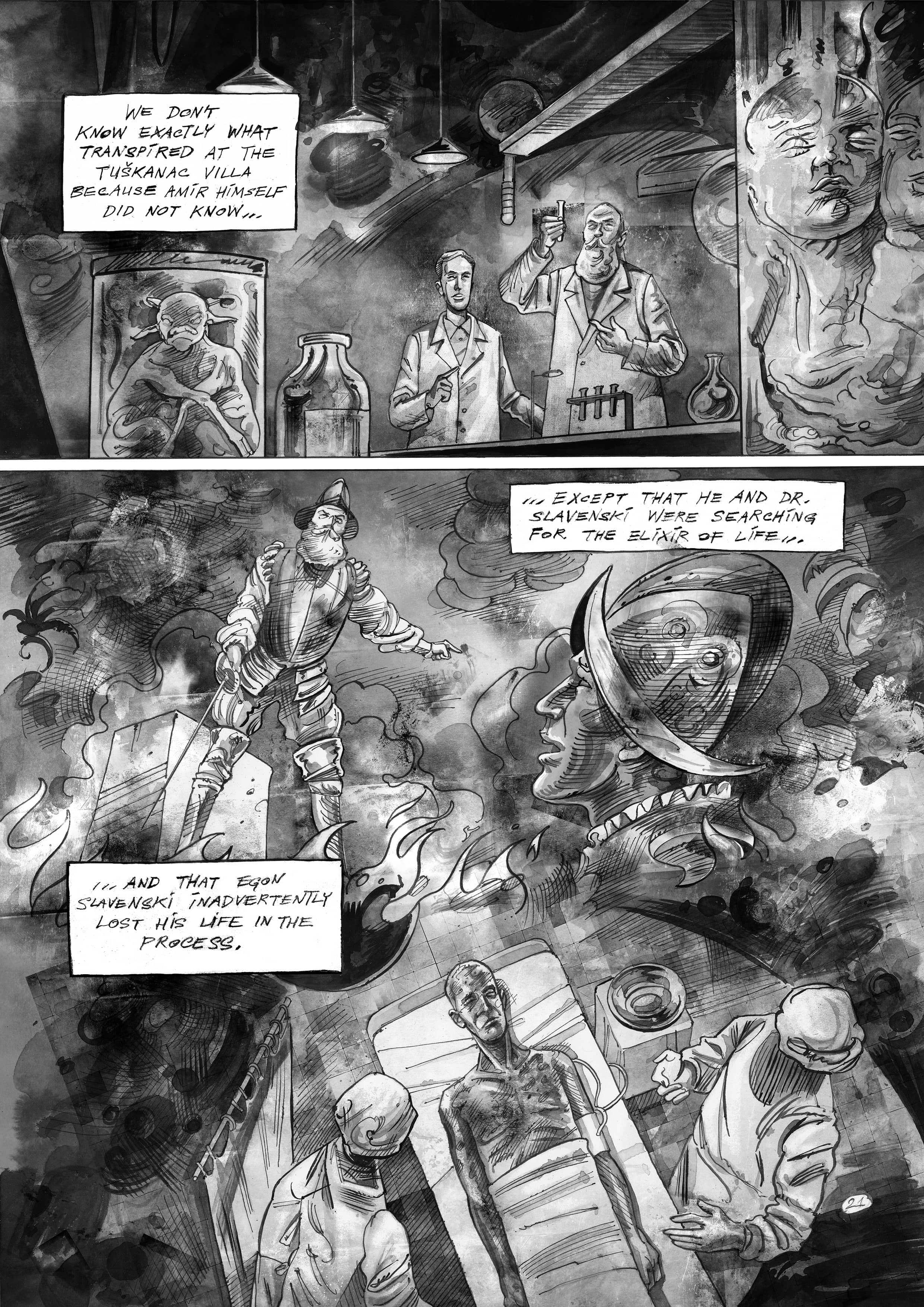

NT: I was translating a chapter from a book which references a poem by an author called Hayim Nahman Bialik, titled “a poem to a bird,” and the text was written by a Moroccan Jew. He recounts that in school they had learned that there is a certain verse which contain the letters ح and ع, two very central letters. This is because Arab Jews, at least the first generations, used to pronounce the ح and ع, whereas the Ashkenazi pronounce the ح as a خ (kh) and the ع they almost don’t pronounce.

This became very important in Israeli society because if one pronounces the ع they are immediately recognizable as a Jew who came from an Arab country. Now these nuances have become blurred. In the text by this Moroccan Jew, he references a word which means ‘small chick’ and which contains both letters. The author says because the teacher was Ashkenazi, they did not learn the other pronunciation and learnt to say both letters the Ashkenazi way. When translating into Arabic, the obvious translation does not contain either letter so I had to be creative to find an equivalent which did. Eventually I was able to get both letters. So sometimes in translation you play around with language to be able to bring out this difference in translation.

As far as my choice of text, right now I am working on a novel by Almog Behar, a Jewish author of Iraqi origin. The protagonists are also of Iraqi or Moroccan origin. The author and the characters are both devout and there is a chapter which concerns Jewish temples, and specifically Eastern Jewish temples (meaning those which came from Arab countries). In these temples, they emphasize pronunciation, meaning what is the correct pronunciation and what is not, similar to pronunciation with regards to Quranic recitation.

So it is very important because, as opposed to Christianity, Judaism and Islam still speak their liturgical languages. In one chapter, the rabbi explains what letters today in Israel are mispronounced and which are not. This applies to many letters in modern Hebrew today which are pronounced differently because the Ashkenazi accent changes the Hebrew equivalents of a hard ط to a ’t’ and the ص becomes as a German Z. So this chapter brings up examples of words which if mispronounced become confused with other words. This is hell for a translator because you are trying to find Arabic equivalents which have the same letters the Rabbi mentions and there is a possibility that they will be confused with other Arabic terms which contain the same letters. It takes a lot of effort but what helps is the similarity between Arabic and Hebrew. The word “rabbi” also presented a challenge: the rabbi is a central figure in the novel. The word for that in Arabic حاخام (hakham) does not sound pleasant and when you make it plural it becomes حاخامات (hakhamat) and that doesn’t sound good either, not to mention the word has a certain political association. The Israeli equivalent to Al-Azhar, I made into حاخامية (hakhameya) and it still didn’t sound good, so I brought it back to its origin which is “hakeem” meaning wise man, from the word حكمة (hekma) or wisdom, as a Hakham is a wise man, and phonetically it makes sense, so Hakhameya became Beit El Hekma (house of wisdom), and Hakham became Hakeem.

I explained this in the introduction but with repeated use, the reader should understand that ‘wise man’, in a completely Jewish religious context, is a rabbi. I also kept using the word معبد (ma’bad) for temple and then decided on the word كنيس (Kanees), which shares the same root with the knesset. This word was used in the early 20th century by Arab intellectuals. The other one معبد (Ma’bad) might mean a Buddhist temple or anything else but كنيس (Kanees) is specific. Finally the word Jerusalem is Yerushalayim, at first I put it as اورشليم (Orshaleem), as it is a word which exists in Arabic as well.

The writer when he saw the draft said, why not القدس (Al-Quds)? But I wanted to get rid of these associations in the Arab reader’s mind and portray a Jewish, not Arab, Jerusalem. So the compromise was that in religious contexts, when it is mentioned it is now Yerushalayim, whereas in secular or everyday usage it became al-Quds.

There is a section where the protagonist goes to East Jerusalem and takes a stroll; over there it is all Quds, but when it’s a prayer, it’s Yerushalayim. Yahweh was a problem at first because in the middle centuries Jews used to translate Yahweh into “Allah” and it was no issue. But I chose to make it Yahweh. I wanted to remind the reader of the Jewish context, even though the author at one point translated the word into Allah, which was the one instance where I kept it.

OA: You assume a particularly active reader?

NT: Yes. I am interested in a pre-Quranic Arabic particularly. The simplistic Arab imagination says that pre-Quranic history of Arabic is the Mu’allaqat, but I go further and interrogate the memory of the root language that gave rise to Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, etc. So when I say I want to remember Arabic in this state, I am also secularizing it by separating its history from the Quran. And in a sense I am trying to secularize Arabic—a holy language for Muslims—through another holy language, Hebrew. So this is the reader’s role for me; I am not trying to point them necessarily in a particular direction, but I use common trilateral roots and make it smooth enough that the reader will read it and not notice but if the same reader pays attention they will catch it.

OA: What does a secularization of Arabic hold for the attentive reader?

NT: At the very least, Arabic becomes an ordinary language and it will evolve. Whether it’s the classical of Quraysh or spoken dialects. I am in love with the Arabic language, and I see it as a very rich language, even in the context of Semitic languages, not as a bias but simply because it has been used as the lingua franca of a very large region, meaning it has been enriched and gave way to many variants. This linguistic variation is important, because as opposed to a standard Quranic language, it was an ordinary language where creativity is possible. For the same reason, I have an interest in Arabic colloquials.

There is a common idea that Arabic cannot express certain things, which I find absurd. The association with the Quran discourages people from being creative with language but if one has enough creativity, the language has the capacity. I would like the reader to remember this creativity and think of the Arabic language with regards to its respective historical development and not as a language which has been given to us divinely.

OA: In your own writing and in translation, how do you navigate the problematics of using the standard versus the colloquial?

NT: I use it whenever appropriate, for example there is a chapter set in red light district chapter in a Hebrew text, I used colloquial for this throughout. In Almog Behar’s book, almost all of it is in Modern Standard Arabic. For this text I felt that using dialect would’ve taken away from its language and given attention to my writing more than the talmudic, sacred atmosphere in the original. In my own writing, I use classical for narration and colloquial for dialect.

OA: In your novel The Women of Karantina, recreating Alexandria hinged almost entirely on language. The fictional Karantina and other aspects of the novel present a very different view of the city. Why did you strive to present this remapping of Alexandria?

NT: I wanted to set it in Alexandria and counter the image of the cosmopolitan city that most people have. Most of us were born after the Europeans left, so we never saw this cosmopolitan Alexandria. I wanted to present a different city: the dirty Alexandria with its prostitution, drugs and crime. In fact, I barely really talk about Alexandria: there is no space. The protagonists go and start the fictional Karantina as a separate neighbourhood and so it ends up not being the real Alexandria, rather an imagined one. The only place that has the most ties to Alexandria is the dialect. It was the most entertaining aspect of writing as my ear is very sensitive to dialects and changes in language. It takes place in the western part of Alexandria, off the coast and away from the sea, so the strongest connection is the language. I would even say the novel could have taken place in Cairo had it not been for the dialect.

OA: Articulating identity through language informs your translation and writing in a profound manner. How do you expect others to surmount translation challenges with regards to your own writing?

NT: Yes, I think of language as the cornerstone of identity. I am more interested in language more than identity; there is a huge debate in Israel when it comes to eastern Jews for example when it comes to language and so hebrew has also influenced and come into this. There is also huge variation in Alexandrian dialect that I sought to present.

Keeping this in mind, there are some compromises that a translator- and more importantly an author- must keep in mind. You write and then you see how it is rendered in translation, not the other way around. I would not keep the untranslatability of any phrase or word in mind as I write. You must have enough wisdom to know what cannot be translated. There is an unspoken agreement between yourself and your native reader that you are presenting her with riddles, and hidden information that is inaccessible to a foreign reader. I did not even think that my novel would be translated, but despite this, I think it is a successful translation and what is important is that the ‘soul’ of the text is transmitted, which I believe to be between tragedy and comedy, between reality and cartoonish absurdism. It moves between parodical academic rhetoric and completely absurdist passages. What is important is that this is transmitted to a foreign reader: that they are able to make this distinction between these two registers in writing. But whether a foreign reader can understand that this is in Alexandrian or Cairene- you give up this idea and make peace with it.

OA: Are there any complications to translating Israeli writing and publishing given the discourse around normalization in Egypt and the Arab world?

NT: It is easy to publish the translated book but difficult to pay royalties to an Israeli institution, as this is seen as a form of normalization. Fortunately, younger writers give it up to circumvent the politics. There was an anthology of anti-war poetry, dealing with Gaza and all the authors were receptive. Almog Behar as well, had the royalties to the book in Arabic, so these issues were avoided. It is usually better for me to talk to an individual (an author) rather than an institution. This does not always circumvent politics; the first book I translated from Hebrew was Idith Zertal’s Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood.

A book about death in Israel, inspired by Benedict Anderson’s ‘Imagined Communities’. Anderson says death is used to create identity, and the author explores this idea from the 1920s until Yitzhak Rabin’s death, as well as issues relating to the holocaust, such as how the survivors were portrayed and collective memory. I worked on it independently without solicitation and I spent 8 years translating it. At the time I did not know anyone in Israel. When I did meet someone in Israel, I asked for the author’s email and I emailed her and told her that I really liked her book and was almost finished translating it but that there would be an issue with paying royalties. She refused to waive them and said she was also concerned the book might be ‘read wrongly in Egypt’, fearing it would be read in a propagandistic way. I published it anyway, as uncomfortable as I was with it, because I did not like that I did it without her involvement but I had worked on it for 8 years. Although it received little recognition in Egypt, perhaps as divine punishment.

OA: How would you describe an emerging translator’s access- especially in the context of Hebrew- to publishing in Egypt?

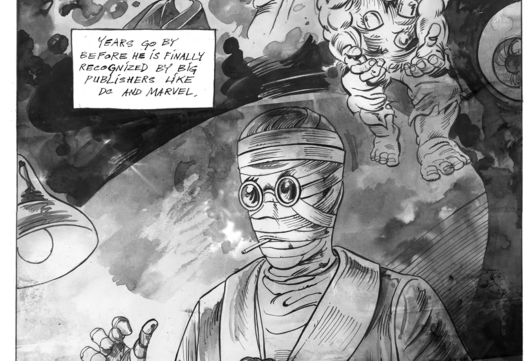

For Hebrew, there is a gap between students studying Hebrew and cultural production. For a middle-class student in an Egyptian university, there is a separation of studying the language and literary or cultural circles. My exposure to this came from my interest in writing. The professors, for instance, have no interest in literary translation. There are some who are excellent at what they do, specifically in the field of linguistics, but they have no connection to culture, and they would never publish in a cultural journal, only an academic one. In some way, I feel a certain pressure- not as a novelist who also translates from Hebrew- but because I am truly passionate about the language, and that is a rare thing to find.

*****