Happy Friday, Asymptote! If you need a pick-me-up this week, here’s a friendly reminder of why translation’s so important: translating books often means saving them (essay comes to us thanks to LitHub, by former contributor André Naffis-Sahely). After all, without translation (and translators), we could never read this New York Times book review: literary phenomenon and badboy Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgaard writes the most Knausgaard-y book review on French writer Michel Houellebecq’s latest-into-English, Submission.

Monthly Archives: November 2015

Weekly News Roundup, 13 November 2015: The Most Knausgaardy

This week's literary news from around the world

Poligon Literary Festival: A Dispatch by Ivan Šunjić

"This year's Poligon boasts three prize winners: Krivokapić, Kaplan, and Pajević."

The first incarnation of the literary festival Poligon was held in Mostar on September 25-27, 2015 at several different venues in the city. The decentralization of the festival and the “occupation” of Mostar’s cultural hotspots by poets and writers helped revive the city’s dormant literary scene. The festival was imagined as a space for dialogue between authors from the former Yugoslavia, an opportunity for strategic planning and strengthening of interregional literary exchange. In the words of Mirko Božić, the initiator and co-organizer of Poligon, the festival hopes to put Mostar on the region’s literary map by providing a multi-medial platform for literature, but also visual arts and music. READ MORE…

Translation Tuesday: Prologue to Bacchae by Euripides

"I have compelled this town to rant and howl, / dressed it in fawnskin, put my pine-cone-tipped / and ivy-vested spear into its hands"

Dionysus:

Here I am, Dionysus, Zeus’s son,

the god whom Semele, the daughter of Cadmus,

birthed, with a bolt of lightning for a midwife.

I am back home in the land of Thebes.

My sacred form exchanged for this mere mortal

disguise, I have arrived here where the Springs

of Dirce and the river Ismenos

are flowing. I can see my lightning-blasted

mother’s tomb right there beside the palace,

and I can see as well her former bedroom’s

rubble giving off the living flame

of Zeus’ fire—Hera’s deathless rage

against my mother. I am pleased that Cadmus

has set the site off as a sanctuary

to keep her memory. I am the one

who covered it on all sides round with grape leaves

and ripe grape clusters. READ MORE…

In Conversation with Annie Zaidi

"...it became apparent at once that women have always used writing as a form of politics and activism."

In a conversation about a younger generation of Anglophone writers in India, Annie Zaidi’s name is bound to come up. From poetry to non-fiction to drama to a novella that is both ghost story and romance, her writing continually shifts forms, landscapes, and languages. Zaidi is the editor of Unbound: 2,000 years of Indian Women’s Writing and the author of Gulab, Love Stories # 1 to 14, and Known Turf: Bantering with Bandits and Other True Tales. She is also the co-author of The Good Indian Girl. Her work has appeared in several anthologies including Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean, Mumbai Noir, Women Changing India, and Griffith Review 49: New Asia Now. Zaidi spoke with me about her influences, process, and literary interests in an email interview.

***

Poorna Swami: Your grandfather was a well-known Urdu writer, and you have said in the past that literature was a big part of your childhood. How has that culture of language and literature influenced your career as a writer? Although you write primarily in English, does Urdu shape your work in any way?

Annie Zaidi: Literature was a big part of my childhood, but not in the sense of literature with a capital L. My family had some literary background, and there were a lot of books around but there were no literary discussions and for many years, I did not have access to a good library. But books were seen as a good thing and we were bought books and comics from an early age. Books were my main source of entertainment and, later, my main solace. I read almost all the time and that turned me into somebody who didn’t know much except the world of words and stories. Turning to literature as a vocation was a very short step from there. READ MORE…

Weekly News Roundup, 6 November 2015: Top Notch, Middle Notch

Highlights, lowlights, and mid-lights in literary news from around the world.

Happy Friday, Asymptote. Hard to believe a week has already passed since the American Literary Translators Association conference in Tucson, Arizona—but it has, and the National Translation Award-winners have been announced: prose honors went to William M. Hutchins’s translation from the Arabic of The New Waw: Saharan Oasis, and Pierre Joris’s iteration of the later poems of famed German poet Paul Celan—collected in an edition titled Breathturn into Timestead—won the poetry bid.

Meanwhile, the Lucien Stryk Prize, which focuses on Asian-language translations, went to Eleanor Goldman, who snagged top prose honors for her translation of Something Crosses my Mind by Wang Xiaoni, translated from the Chinese (be sure to read some of Goodman’s Wang Xiaoni translations in our July 2014 issue here!). And the Italian Prose in Translation Award went to Anne Milano Appel, for her translation of Blindly, by Claudio Magris. Congrats to all!

What’s New in Translation? November 2015

So many new translations this month! Here's what you've got to know—from Asymptote's own

War, So Much War by Mercè Rodreda, tr. Maruxa Relaño & Martha Tennent (Open Letter Books)—reviewed by Sam Carter, assistant managing editor

“The sleep of reason produces monsters,” reads one of the epigraphs to Mercè Rodoreda’s Quanta, quanta guerra, now available in English as War, So Much War from Open Letter Press. Drawn from the title of a famous Goya etching, it is a fitting prelude to a work that explores the ravages of war from a pseudo-picaresque perspective in which we find ourselves face-to-face with a narrator coming to terms with the unnerving and unending monstrosity of war, rather than encountering a delinquent carefully crafting a tale of struggle and self-justification. Even if this conflict initially resembles the Spanish Civil War, in his narration, protagonist Adrià Guinart insists on an ambiguity permeating all levels of the work and suggesting the plausibility of less localized interpretations.

In sparse prose, crisply translated by both Maruxa Relaño and Martha Tennent, Adrià recounts his interactions with the figures he meets throughout a journey that begins with an enthusiasm for the escapist possibilities of war and yet ends on entirely different note. His own narrative “I” proves elusive as it frequently disappears into a chorus of other voices that dominate the task of depicting a war-torn landscape. Describing the novel’s structure with another of its epigraphs—“A great ravel of flights from nothing to nothing,” from D. H. Lawrence—is ultimately too tempting to pass up, for it is precisely in its itinerant quality, in the way it moves from one episode to another without the need to establish definitive links, that the novel finds its strength. READ MORE…

Portions of assistant editor Alexis Almeida’s translation of Florencia Walfisch’s Sopa de Ajo y Mezcal were published at the Fanzine. She also had the poems “Study of My Body the Pantomime” and “17 Sounds for Saint Cecilia” published in Matter Monthly, and she contributed to an Insect Poetics feature in the Volta. Futhermore, Alexis recently had both translations and poems published in issue two of Divine Magnet.

Slovakia editor-at-large Julia Sherwood’s translation of the short story “The Wall” by Hubert Klimko-Dobrzaniecki—translated from the Polish jointly with Peter Sherwood—appeared in the September issue of the Missing Slate. READ MORE…

Translation Tuesday: from Looking at Pictures by Robert Walser

“When he felt his earthly end approaching, it irritated him somewhat that he had evidently produced, alas, almost a little too much.”

Diaz’s Forest

Translated by Susan Bernofsky

In a forest painted by Diaz, a little motherkin and her child stood still. They were now a good hour from the village. Gnarled trunks spoke a primeval tongue. The mother said to her child: “In my opinion, you shouldn’t cling to my apron strings like that. As if I were here only for you. Benighted creature, what could you be thinking? You’re just a small child, yet want to make grownups dependent on you. How ill-considered. A certain amount of thinking must enter your slumbering head, and to make that happen, I shall now leave you here, alone. Stop clutching at me with those little hands this instant, you uncouth, importunate thing! I have every reason to be angry with you—and I believe I am. It’s time you were told the unadorned truth, otherwise you’ll stay a helpless child all your life, forever reliant on your mother. To teach you what it means to love me, you must be left to your own resources, you’ll have to seek out strangers and serve them, hearing nothing but harsh words from them for a year, two years, perhaps longer. Then you’ll know what I was to you. But always at your side, I am unknown to you. That’s right, child, you make no effort at all, you don’t even know what effort is, let alone tenderness, you uncompassionate creature. Always having me at your side makes you mentally indolent. Not for a minute do you stop to think—that’s what indolence is. You must go to work, my child, you’ll manage it if you want to—and you’ll have no choice but to want to. I swear to you, as truthfully as I am standing here with you in this forest painted by Diaz, you must earn your livelihood with bitter toil so that you will not go to ruin inwardly. Many children grow coarse when they are coddled, because they never learn to be thoughtful, thankful. Later, they all turn into ladies and gentlemen who are beautiful and elegant on the outside but self-absorbed nonetheless. To save you from becoming cruel and succumbing to foolishnesses, I am treating you roughly, because overly solicitous treatment produces people free from conscience and care.” READ MORE…

Best European Fiction 2016: A Conversation With Editor Nathaniel Davis

"There’s nothing great about a translation if the original’s no good."

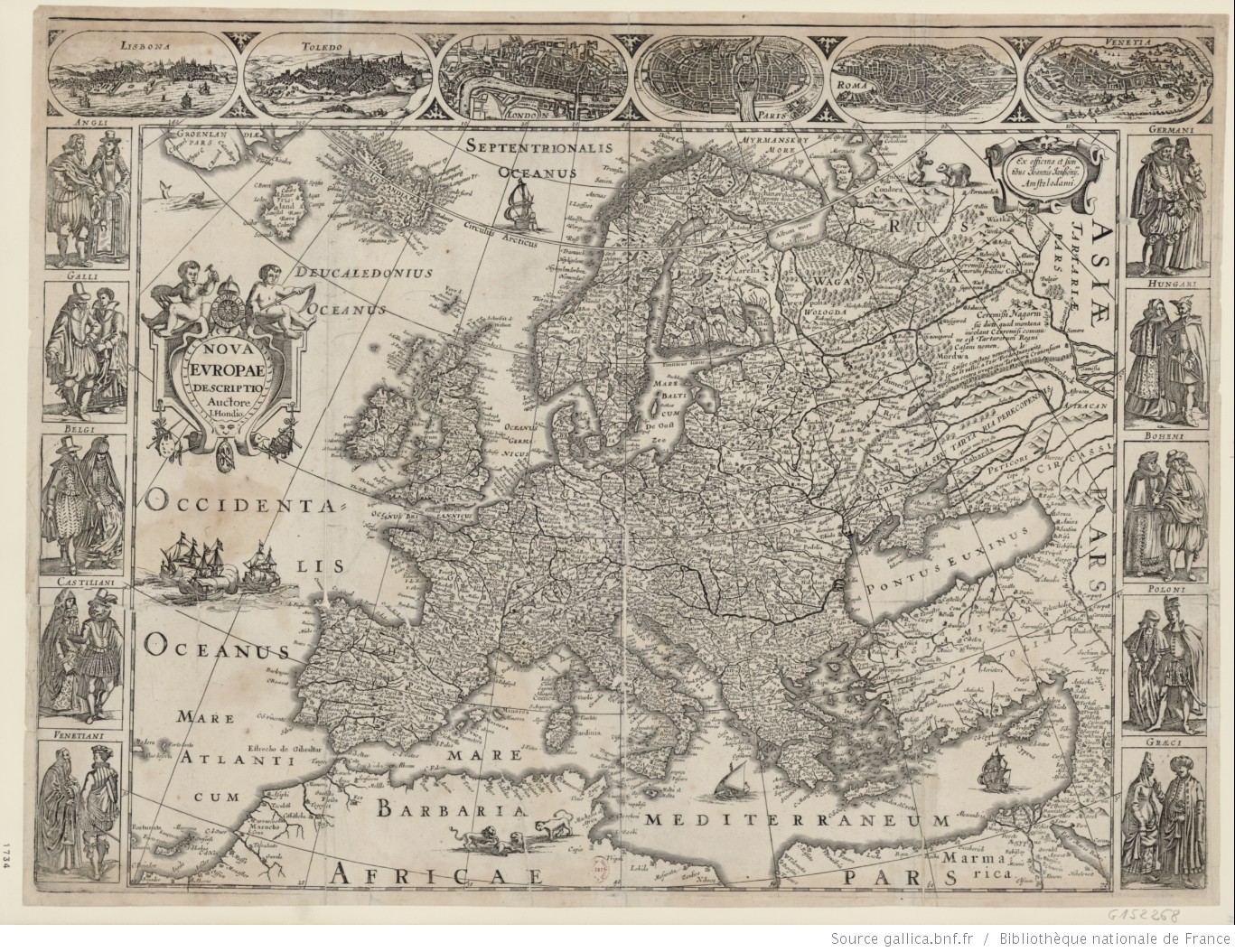

The first volume of Best European Fiction, from the year 2010, brought together stories from 30 countries—introducing fiction by well-established writers such as Alasdair Gray and Jon Fosse in addition to stories by emerging European writers who had not yet been translated into English. Over the last six years, the series has published more than 200 stories from countries across Europe, from Iceland to Russia.

At a time when publishers are publishing dramatically less writing in translation, Dalkey Archive Press will release Best European Fiction 2016 on November 13. In an email interview, the volume’s editor, Nathaniel Davis, described the process of continuing to provide English-language readers with new artistic and intellectual windows that open out on to Europe.

***

MB: The call for submissions for Best European Fiction 2016 received more than 150 stories. Describe the process of whittling that number down to 29. What were your toughest editorial decisions? For example, were you conflicted in choosing between two authors from the same country?

ND: The way the selection process works, we choose one story from each country, and multiple stories for countries with more than one national language. So we might have both French and German stories from Switzerland, or French and Flemish stories from Belgium. Part of the project of Best European Fiction is to highlight writers from neglected linguistic traditions. So BEF2016 has Spanish stories written in Basque and Catalan, but not Castilian (although we often also include Castilian authors). After the primary selection of the best submissions, we have to whittle it down to about thirty, taking space and funding into consideration. We ask the participating countries to contribute some financial support to the anthology, as it’s a very expensive undertaking that doesn’t pay for itself (despite usually selling pretty well). READ MORE…