From August through December 2012, I was almost physically unable to read books. Picking up a book, I found myself incapable of the sustained concentration necessary to make sense of phrases, sentences, paragraphs. I would read the same thing over and over again, my mind wandering into blankness. It felt, in a very real way, as though my eyes were slipping off the page. Reading books had always been a means of sustaining myself, and so forgetting how to read was very much like forgetting how to eat.

I would be lying if I said it wasn’t frightening. The qualitative aspect of this bizarre reading aphasia (for lack of a better term) was a persistent feeling of restlessness when I was trying to engage with a book—as though my brain would rather be doing something, anything, else.

This condition mostly persisted until late April of last year, when I moved from the countryside of Pennsylvania—where I’d lived within a stone’s throw of dilapidated barns and old orchards—to Oakland, California. I had hoped that the warmer weather, the change in time zone, and my new proximity to an actual city would shake something loose in my head.

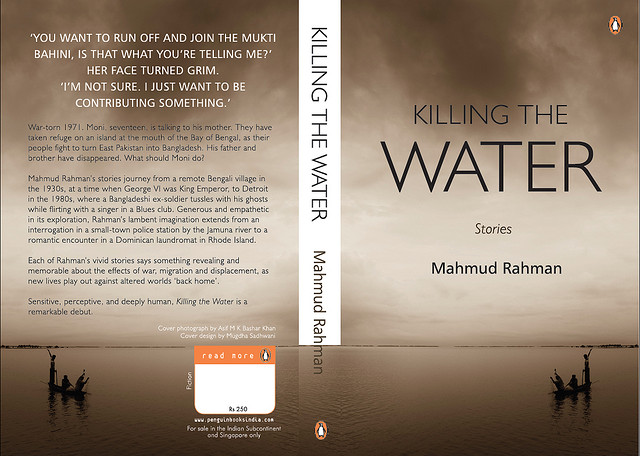

Within a few weeks of my arrival, I’d found and finished Mahmud Rahman’s Killing the Water, a collection of short stories that moves from Bangladesh to Boston to Detroit and finally to Oakland.

It was a comfort, personally, to read something in which characters were almost constantly moving, from either one place or one state of being to another. As someone who was feeling both unsettled in place and in temperament, I identified immediately with the collection’s theme of transition and adaptation. (While reading the book I was reminded, at times, of Arjun Appadurai’s discussions of “ethnoscapes” and the movement of groups and the remaking of identities, something which Killing the Water depicts skillfully, especially in the latter stories that feature immigrants from Bangladesh living and working in American cities, struggling with the choice of what to keep from their old lives and what to leave behind as they engage with a new culture.)

This book also felt like it was written with care, and only realized through a great amount of effort. Which isn’t to say that the collection feels “worked over,” though Rahman, who is also a translator—of Mahmudul Haque’s Black Ice—shows a translator’s knack for control and restraint and for knowing when to deploy the kinds of sentences that beg to be underlined. I mean that these stories feel homemade, in a way that not a lot of stories do.

There is a sense, to me at least, that this book was the result of rigorous introspection, careful observation, and recollection—mindful labor, in short. Killing the Water is a somewhat old-fashioned book, a personal expression, fiction that feels like an echo of fact, of experience (though that approach is perhaps in vogue again, viz. the rapturous reception given to Knausgaard’s fine-grained recollections in My Struggle).

Though there’s plenty of invention here too. Rahman has a good hand for turning a plot in a surprising direction. There were a few stories—“Before the Monsoons Come” and “Kerosene” spring immediately to mind—that ended with devastating scenes, in some ways reminiscent of Flannery O’Connor’s work, where you can only see in painstaking retrospect the moves that the author made to produce such emotional impact.

“Kerosene,” which takes place during the Bangladesh Liberation War, is an especially harrowing read, along the same lines as something like “A View of the Woods,” with the inevitably of violence embedded in the first page and only reaching full, terrifying expression much later. Like O’Connor, Rahman explores the ways in which feelings of familial or religious obligation motivate people to commit selfless acts or (more often than not) to make heartbreaking choices in order to survive, to get ahead, to move on. In one of the collection’s best stories, “Interrogation,” the main character, a police interrogator, makes a choice to let a juvenile offender go free; though nominally a merciful decision, it’s revealed later in the story that the interrogator was motivated by the promise of a lucrative job, extended to him by the boy’s powerful and wealthy father.

Killing the Water is a very human book in many ways. To me, there are two kinds of books that produce profound feelings of readerly amazement: those that seem as though they could not have come from one person, that seem like they are beyond the limits of human accomplishment and thus feel somewhat unreal (e.g. Ulysses, At Swim-Two-Birds, Wise Blood, Infinite Jest, and 2666, among others); and books like Killing the Water, which seem like they could have been written by a friend or by your next-door neighbor (like, say, Irmgard Keun’s Gilgi, Michelle Orange’s Sicily Papers or Patrick deWitt’s Ablutions), or in any case by someone who has the same worries, fears, and afflictions that you do. Killing the Water is a companionable book—unbelievably fun to read—and I’m glad that I found it, because it allowed me to read, and keep reading, once again.

****

Kevin Hyde’s fiction has appeared in Parcel and Big Fiction and online at Gigantic and Eyeshot, among other places. He blogs about music at Molars (molarsmolars.com) and lives in Oakland, CA.