My first literary entanglement—or the first one I remember—was with folktales. While Danish and German tales were undoubtedly my introduction to the form, by the time memory kicks in, I am scouring local libraries and filling Christmas wish lists with requests for Greek myths, Norwegian sagas, Chinese tales, Italian fairy stories (yes, the Calvino), and any others that an intrepid relative might find.

Even as a young adult, I continued to savor the form, which I discovered when I found Inea Bushnaq’s Arab Folktales in my early twenties.

After all, there is something profoundly, resonantly human about the folktale, even when read across wide cultural and historical gaps. As Ursula Le Guin notes in her 1980 review of Calvino’s collection, the best fairy tales evoke an almost uncanny sense of familiarity. Rare is the collection equal to Calvino’s, yet memory and transmission themselves have acted as good editors.

Calvino’s folk tale collection was published in the 1950s, and published in at least two English-language editions. Although anyone could enjoy these tales, both translations are targeted at children. After all, by the twentieth century, the European folk form had become strongly associated with young readers. Yet for thousands of years of human history, the oral “folktale” was an all-ages affair, true even across widely variant cultures, where oral tales often featured similar tropes and mnemonic devices.

A thousand invisible threads

These similarities are hardly surprising, as folktales weren’t locked up inside a particular culture. Thanks to travelers and translators, folk and fairy tales from different traditions are linked by a thousand invisible threads. Many American readers assume that Hans Christian Andersen wrote in English. He, in turn, was raised on translations of the One Thousand and One Nights. In recent centuries, hundreds of anthropologists have gone out like butterfly collectors, gathering tales, and hundreds of translators have brought them from language to language.

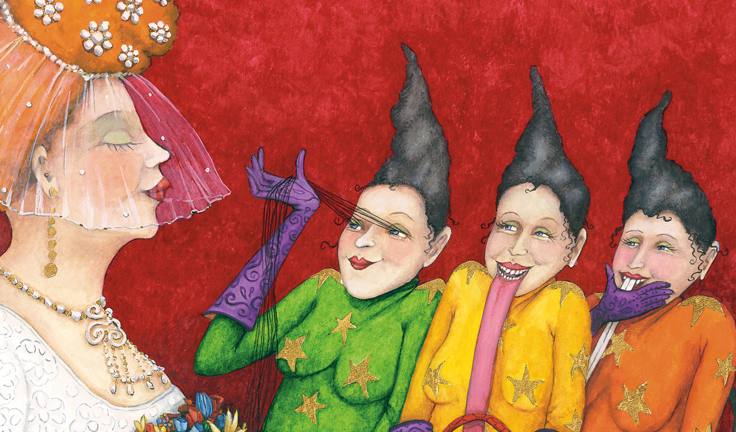

As this happened, so did the reimagining of folk tales as stories for children. Once upon a time, folktales were quite raunchy, something true not merely of the Nights, but also of the Brothers Grimm, although most of this “adult” content has since been excised. Some authors, such as Yuri Rytkheu, still write beautiful folktales addressing the full spectrum of human experience. But for the most part the folktale has largely been sent off to live in brightly colored children’s books.

As tales were collected, translated, reimagined, and sent to the nursery, they generally lost their fangs. Much of the blood and lust were swept away. The Nights is among those collections that has been targeted by censors, and this has recently raised an outcry. Yet there’s little outrage that the Grimm brothers cleaned up their tales. For the most part, it’s expected. As an anonymous Amazon reviewer wrote about Ibrahim Muhawi and Sharif Kanaana’s collected Palestinian Folktales: “Not what I expected, and definitely not fairy tales to be read to children – many sexual references.” In the public consciousness, “folktale” has come to mean something innocent.

A number of writers and thinkers have lamented these erasures, particularly those of violence. Yet the folktale, even denuded of “adult” matters, still gives us a lot to chew over and enjoy.

How would we know they’re translations?

By the 1980s, there were a great variety of folk and fairy tales available for child-readers. I grew up on a steady diet of tales, as did a number of others who came to love translated literatures. For many children, particularly in the US, these folktales were nearly our only exposure to literature in translation—even if we didn’t know them as translations per se.

Nowadays, there is a (slightly) wider range of translated children’s books in English. Yet folktales are probably still the translated works with the broadest reach—particularly in the U.S., where Asterix and Tintin have yet to make inroads. In the last thirty years, folktales have also expanded their range, although with the same unfortunate omissions. While it’s easy to find well-crafted collections from individual European countries, there are, by contrast, far too overbroad and often disappointing “Latin American” and “African” collections.

Another thing hasn’t changed: there is still no mention, on most of these collections, of a translator. When I devoured tales as a child, I had absolutely no notion that they were translated. As an adult, I can comb through the tiny print and see that my edition of Italian Folktales was brought to English by George Martin. But as a child, I surely thought Italo Calvino wrote and spoke in American English. Ursula Le Guin suggests that Martin’s translation is a rather clunky one, inferior to the earlier re-vocalization by Louis Brigante. Perhaps it is. But, either way, why shouldn’t children be capable of knowing of Martin’s involvement?

Browsing through folktale collections, I rarely see a translator credited or announced in a prominent place. I do understand the desire, even if misguided, to keep sex and violence away from children’s books. But my sons can handle knowing their Calvino was translated.

Indeed, why hide translators? While I can easily find dozens of children’s nonfiction books about authors, firefighters, artists, nurses, and even lawyers, I turn up none about translators. Surely we could accustom children to the idea that, just as stories have been brought to them from all corners of the world, remarkable people called translators have been able to re-voice them in English. Surely many children would be keen to know.

***

M. Lynx Qualey lives with three child-readers of ever-increasing ages. She has a particular love for Arabic children’s literature, but is broadly interested in how narratives for children are shaped around the world. She blogs daily at http://www.arablit.org.