Even if what is put in writing should at first glance appear to be an almost chance incision through the processes of thinking, experiencing, remembering, narrating: only from here will thinking, experiencing, remembering, narrating be possible. Constriction and freedom are almost one, the eyes closed, fields of light becoming visible on the screens of the eyelids, colours emerge, more clear and pure than real objects might be expected to be, connections intangible and obvious at once. Every place must seem familiar, precisely because one discovers the place in its secret; every movement must appear like a gliding back into the interior of the object. As if there was a remembered space that had survived intact the deaths, translations and interpretations and could be entered, over and over again, with somnambulistic sureness; but within oneself something always remained—the wound, the incision—that kept that space at a distance. In a short story by Borges a man named Joseph Cartaphilus follows rumours of a river whose water bestows immortality and of a City of the Immortals rich in bulwarks, amphitheatres and temples. Moving westwards from the Nile (the Egypt), his route takes him into a region clearly identifiable yet hidden behind the deserts, as if concealed by a fold in the maps. That a famed city should be harboured in the bosom of these barbarian territories where the earth spawns monsters, he (Cartaphilus, Borges) writes, seemed inconceivable to us all. He strays through the black desert; on the brink of thirsting to death (in the course of a single, monstrous day multiplied by sun, thirst and the fear of thirst) he sights, on the other side of a cloudy river faltering in its course due to debris and sand, the pyramids and towers of the town on a black slate mountain; he dreams of a tiny, shining labyrinth. Borges' story tells of consummate gain and utter loss (for eventually it loses the narrator), but lets words, when the end approaches, survive.

In Book II of The History Herodotus tells of a group of young adventurers from the Syrtis region, the sons of Nasamonian princes, who in the course of an expedition, seemingly some kind of rite of initiation, journey further from their native land than anybody before; they traverse the territories of Libya, inhabited solely by wild beasts, the endless sand deserts, and as they set about plucking fruit from a tree in an oasis are seized by small, dark-skinned men. These people are sorcerers; they take their captives across marshy territories to their city that is bisected from East to West by a vast river teeming with crocodiles. Scenes must have followed in which questions remained unanswered, futile attempts to communicate were made, accusations made or explanations given; the town with the river with no name (with the river that will change names and places alike) seems to the captives (we shall hold onto this fear) like a region without language, a region in which one's language is lost; yet the embroilment in translations, misunderstandings, in the fears, the pride and the isolation of the untranslatable, does not seem to have been hopeless. Herodotus, who heard the story from several Cyrenaeans, who for their part heard it from the king of the Ammons, whose court was once visited by Nasamons, says nothing about how the young men got back to their native land; about whether they were set free in an act of kindness or disinterest or under the terms of some kind of contract (and reciprocal deceit), or whether they escaped, by force or cunning, in an adventurous flight of which the details have not been, and shall never be, recounted. The closer one comes to the edges of the world, the more wildly do grow together, in the realms of description, the landscape and its inhabitants. Southward of the Nasamons, in the region full of wild animals (ostriches that live below ground, tiny one-horned snakes), live the Garamantes, who shun all contact with human beings, possess no weapons of war and do not know how to defend themselves; they have settled upon a hill of salt over which they spread a thin layer of soil in order to grow cereals; the horns of their cattle turn downwards, and the grazing beasts have to walk backwards so as not to become stuck in the ground. Egyptian images do not show Garamantian farmers and cattle-breeders, however, but warriors and generals: the outlines of tall lean men with braided hair and tattooed arms kneeling or standing by the stone wall of a king's grave, wearing pearl-studded loincloths and belts strapped lengthwise and crossed over the breast, or variously patterned open cloaks, pointed beards on all of their chins; their long hair is adorned with feathers, in their hands they hold swords, axes or bows. In chariots of war drawn by four stallions the docile and defenceless Garamantes hunt down, as Herodotus soon himself relates (it is the first in a long series of about-turns), the Ethiopian cave-dwellers, the Troglodytes, who instead of speaking emit shrill calls like bats might do; they also flit about almost like bats, but flat on the ground, more fleet of foot than any other kind of human being one has ever heard of. They live on snakes and lizards; one can imagine how, little more than shadows themselves, they follow their prey into the cracks in the soil, the tiny crevices in the rocks, soldiers (hunters, athletes) from the North, almost Europeans, hybrids of human beings, animals and machines, thirsting for their lives: we imagine the Troglodytes to be always naked, as if skinned, to be as defenceless in sleep as a litter of mice, hearts beating fast and fleeting, on the ground, in the caves they share with the reptiles, with great, fragile insects with translucent wings, and with their brothers the bats. During a long-winded account of a battle in The Aethiopica, a fourth-century adventure novel in which Heliodorus (an Hellenic bishop who is speaking about barbarian heathens) with genre-founding mendacity describes the trials and tribulations of chaste lovers possessed of unearthly beauty who keep falling into captivity, being torn asunder and reunited, being threatened with death or (worse still) forced marriage to strangers, unbelievers, the Troglodytes make a brief re-appearance as naked, unshod and scantily armed warriors whose greatest art lies in avoiding combat; as soon as they notice the superior strength of a foe, they take refuge inside cramped holes and hidden crevices. They are able to outrun horse-riders and chariots; fighting and dying is a game to them. On their heads they wear a crown of arrows made from dragon vertebrae, as they fire one arrow after the other they leap about, bold as Satyrs, with a floating grace that their clumsy foes find provocative and ghostly. Their nakedness gives them bodies and disembodies them at the same time.

On his path towards the mysterious city Joseph Cartaphilus passes through the lands of the Troglodytes and the Garamantes then reaches (if we are not mistaken), ten days' journey westwards, the hill of salt upon which live the Atarantes, the only people without a name; they are waiting for death and curse the sun that with its ferocious heat is destroying their country and anything that lives; after ten more days' journey westwards he would see the Atlas mountains before him, small and circular, raised like a pillar to the heavens, losing themselves in the clouds; their inhabitants, the Atlantes (they seem to have moved closer to the boundaries of the world of plants), eat no living creatures and never dream; to us that seems close to the most extreme dream. The actual City of the Immortals is accessible only by a well and an underground chamber with nine doors (of which only one opens onto the path through the maze), the town is deserted, its confusing architecture, totally opposed to all purposes, rouses deep despair in Cartaphilus as long as he remains mortal. Naked grey-skinned men live, mute and impassive, in the caves outside the city; Cartaphilus believes them to be Troglodytes, later notices that these half-animal, apparently degenerate beings are the fatigued immortals lost—caught between the mirrors—in their indifferent thought who left their city centuries ago, destroyed it, and rebuilt it as a parody.

*

In the Augustinian era a certain Cornelius Balbus from Gadés in Spain is the first immigrant to be honoured with a victory procession, mounted in recognition of his campaigns against the Garamantian cities. He conquered Talgae on the other side of the black mountains of Phazaia, Debris—where by some miracle hot water gushes from a spring for twelve hours of the day, cold water for the other twelve hours—and the famed capital city Garama, the towns of Cyramus, Baracum, Buluba, Alasit, Galia, Balla, Maxalla and Zigama; Pliny, who records this history, lists twenty-five places. A river called Dasibari, which he mentions, is considered by some to be the Djoliba, the Niger; in that case Balbus would, in an inconceivable effort, as the leader of an army of which countless soldiers must have perished in the desert, have foreshadowed conquests of later millennia without leaving any trace in the landscapes traversed, without being able to chart these territories in the maps of the global empire whom he serves. Only by chance would he have survived together with several of his peers and for one brief moment been able to live, a celebrated hero, his senseless triumph in the capital city, before returning to oblivion within a short period. On the waking side of history the destinations of the Romans, and the services rendered to them by the foreign army leader, are more easily identified. Pliny writes of a mountain called Gyri where precious stones—carbuncle or lapis lazuli—are won; today it is known that the Troglodytes, who are quick to take on human form, mined these semi-precious stones and that the martial campaigns of the Garamantes in the course of time changed into trading relationships; they bought the stones from the Troglodytes for use in cowrie shells such as are to be found in the ruins of their cities and continued to be used, fluctuating rapidly in value, in a vast area stretching from West Africa to India up to the time of the later conquerors and colonialists. It is also known that the houses of the Garamantes, just as later the houses in the villages and towns of the Sahara and the territory to the south, were built of clay and generally consisted of a single, windowless room shared by people, goats, cattle, swine, sheep and dogs. The Garamantes loved their dogs, it would seem, and trusted them; in a section of his Natural History that deals with house pets, Pliny mentions a nameless Garamantian king who is fetched back from exile by his two hundred dogs: a focused march of the animals that, mute and emaciated but with bared teeth and slavering chops, charge through the desert for hundreds of miles, the sight of them enough to frighten off anybody planning to obstruct their progress, a protection seeming less effective in the waking world. One begins to guess the fate suffered by the Garamantes captured by the Romans and taken back (alongside the more valuable stones) as slaves or exhibits. A floor mosaic uncovered in Leptis Magna on the Libyan coast shows a barbarian, identified by many as a Garamant, standing upright, chained to a bar: he is a picture-book savage, an almost naked man with deep-set eyes, crooked nose, fuzzy hair and a straggly beard, two beasts of prey are in the process of mauling him.

The storytelling laws that journeys to the end of the world must follow are perhaps residues of half-forgotten magic rituals, and each of the journeys amounts to a repetition of and variation upon earlier journeys; the real merely follows (up to the point of fatigue) these laws throughout the course of the history. The traveller must overcome exertions, delays and deadly dangers, a sequence of odious legs of the journey like layers of emptiness; he must survive injuries, a kind of dismemberment, a most extreme loss juxtaposed by a dubious gain; he must, in order to discover something, destroy what he wants to discover, or destroy his own wish to discover something: a field of possibilities between the real and imaginary, between the murder, the disenchantment and disappointment, and the self-extinction. The foreign and one's own dream of foreignness (the equilibrium between the own and the strange) are at stake, the names threaten to change from mysterious ciphers into mere designations. Virgil, the poet of the state, flatters his Emperor by saying he would extend the rule of Rome to the Indians and the Garamantes, all the way to the most extreme, almost other-worldly, points of the earth; having got there, however, all one finds are real people, who can be killed; one has merely expanded the network of real routes. Prior to the Roman conquest it was impossible to keep open roads into the land of the Garamantes because only they (Pliny, a good propagandist, talks of bands of robbers) knew the locations of the waterholes concealed beneath a layer of sand; they could uncover the water effortlessly, whereas any invader would be bound to die of thirst. A Garamantian trade delegation is reported to have arrived in Rome some time after the war; the attention roused by the virtually naked, tattooed and painted ambassadors with their black pigtails glistening with butter (the girls love them) soon dissipates; throughout the next centuries trade relations between the periphery of the empire and its centre are many-sided and fertile for both sides, without either side being in the least interested in the other.

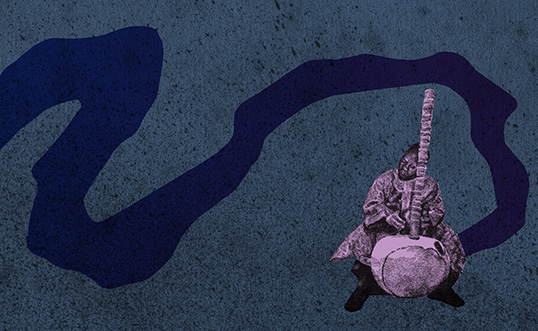

Several of the roads will have survived up to the present day as caravan routes and have been transformed into asphalt ribbons (few cars drive along them; travelling for hours on end through a landscape in which nothing moves except for, imperceptibly slow, the sun in the sky; to be alone with the daylight, before the mountains appear on the horizon, sometimes a thin layer of blown sand covers the asphalt). What particularly strikes the travellers (tourists or archaeologists) in Fezzan near the village of Germa, formerly a noted capital city, are the extensive fields of graves; graves in various forms, weathered stone monuments on the bare plains or dark birds' nests on the mountain slopes, the number of graves has been estimated at fifty thousand: there are little pyramids and step-escalated pyramids modelled on the Egyptian or Hellenic originals, there are towers made of great stone blocks, pointed towards the top, as if a Christian church, roof and all, had sunk into the desert, there are, on the slopes of the mountains, stone wreaths around the places in which dead bodies were put to bed, so it seems, to sleep under vigil. The skeleton (at least one has remained and has not been desecrated by grave robbers or gnawed at and tugged off by voracious animals but instead been placed in a museum and inside a reconstructed tomb) lies with its knees drawn up, in the foetal position, in the middle of the circle; leant up against the lower walls, as if for an animal pen, are the amphorae in which intoxicating drinks are provided for the dead for their life in the next world; outside these walls a stele, taller than a man, in the form of a four-fingered thumbless hand, protects the place and its permanent residents. Engraved on the hand are several signs in a script known as Tifinagh that some Tuaregs can still decipher and interpret.

After the destruction one can let the picture return, at a safe distance, on the other side of the border from which the open palm turns one away with the stop signal. Skin that is tightened around the round of the eyeball, visible behind the names, the legends, the cultural garbage, the ghosts of those cave dwellers who are buried under strata of time, with no firm hold, no chains and no outlook, as is the way of things with ghosts. In the imagination of the German Africanist, impostor, lover and madman Leo Frobenius, the Garamantes emerge from the darkness after centuries, now wandered to West Africa, to where they, founding empires, transpose their culture and make sure that nothing legible to the Europeans and, as they think, part of their heritage, has wholly disappeared from reality. Perhaps in somewhat direct fashion we are pursuing a similar objective to that German professor, less gullible than he, more modestly remaining in the world of letters. Yet there is the moment when the sentences close up; any analogy becomes impossible because one searches for connections in vain and the hands grasp after nothing; the ground beneath the feet is one thing, another is the sentences that are passed between writers and readers, the letters on paper, in stone. A sudden last connection, then, a last thought in his severed head (he, the person who emerges at last, feels his way out of the emptiness, indeterminate and always in the wrong time, who sets out on his way and is already at the end of his way), the place is established, scarcely anything besides, it has to be a thought, a sentence, that is appropriate at this border, belongs to a history that is to take form at the border between the real and the illusory, between the own and the alien; a vanishing sentence: here definitions arise and vanish. A hopeless endeavour, trained on what was never experienced, keeps the game in progress; an attempt to get closer that never succeeds because the yearning always revolves and proliferates within itself, almost without a bearer.