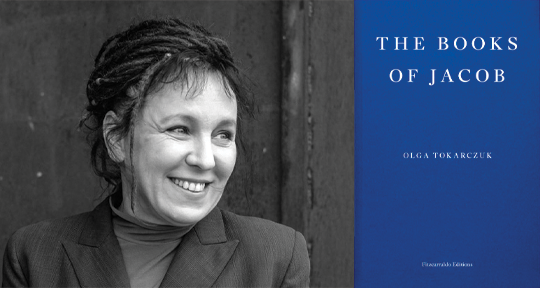

Olga Tokarczuk has long been recognized in Poland as one of the most important authors working today, but it is only in the last few years that she has received her due recognition in the English-speaking world. The course of her rise to fame in English has been in some ways unexpected, beginning as it did with one of her more experimental fictions, Flights, which is also among her longer works. Although this seems to bode well for her continued success, it is in some ways unfortunate that Flights was the first of her novels to receive such attention, because it may give readers the wrong impression: Tokarczuk’s work, though ambitious and wonderfully complex, is in fact best characterized by an extraordinary vivacity and approachability.

That this grace and elegance can also be appreciated by Anglophone readers is due, in part, to the brilliance of Tokarczuk’s translators, and the particular genius of Jennifer Croft is once again on display in The Books of Jacob. Croft beautifully captures the distinct quality of Tokarczuk’s prose: the lightness, the playful curiosity, the lyricism. This is harder than one might think: I translated a few lines of The Books of Jacob myself for an academic essay I wrote on the novel, and it is humbling to compare my version to hers. As Croft recently explained in an essay on the process of translating the novel, part of the trick is managing word order, a complex phenomenon in Polish that, if rendered too faithfully in English, makes for an awkwardness that is utterly alien to Tokarczuk’s style. To get her right, it is necessary to take some liberties, and it requires a truly gifted translator to find the right balance.

A big part of what distinguishes Tokarczuk’s work is its spell-binding immersiveness. Many of her novels, like the much earlier Primeval and Other Times and House of Day, House of Night, have a fairy-tale quality (one that has much in common with the works of magical realism so popular in the 1990s), produced in part by her fondness for interweaving notes of magic or mysticism but also more generally by her narrators’ sense of wide-eyed wonder at the world. The Books of Jacob is very characteristic in this regard, particularly in its interest in the occult and otherworldly. At the opening of the novel, we meet Yente as she awakens on her deathbed and suddenly floats above the scene, viewing everything from on high. “And this is how it is now, how it will be: Yente sees all.” And so the story begins, establishing a perspective that hovers between life and death, outside of time and space, a striking combination of detachment and sensuous detail. At one moment, it ponders the conventions of geographical borders; at another, it notes the particular scent of a sweaty body.

But against expectation, Yente is not the novel’s narrator, nor even the book’s focal point, though she reappears occasionally to survey the scene and meditate on the vagaries of human designs and plans. Instead, the novel moves among a sprawling cast of characters, each with their own wonderfully idiosyncratic set of concerns and interests. There are the various members of the Shorr family (it is they who inadvertently make Yente immortal, having attempted only to keep her alive long enough that her death wouldn’t ruin ruin the wedding they are hosting.) There is the priest and encyclopedia author Benedict Chmielowski, who dreams of describing the entire world, and his pen-pal and aspiring poet, the noblewoman Elżbieta Drużbacka. There is the doctor Asher Rubin, whose cosmopolitan interests in European culture and philosophy draw him gradually away from the Jewish community. And one of my personal favorites, Moliwda, a lonely, wandering Polish nobleman who moves to Turkey, giving himself over to various utopian experiments in search of a place where he will belong. From these bits and pieces of the various characters’ lives, gradually, a larger story emerges.