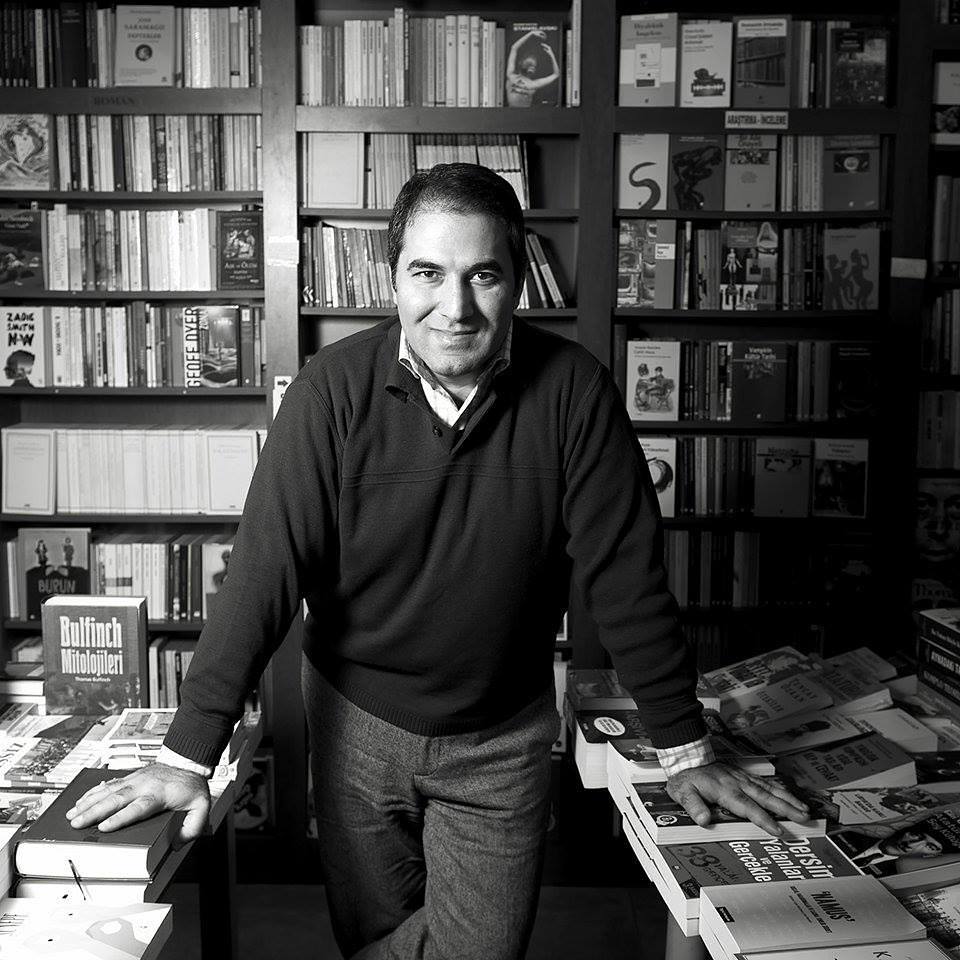

In the 2023 documentary Translating Ulysses, Turkish filmmakers Aylin Kuyel and Fırat Yücel chronicle the painstaking efforts of poet and translator Kawa Nemir in rendering James Joyce’s “untranslatable” tome into Kurdish. This herculean task, which may seem rooted in the desire of any lover of literature to share a classic text in their native language, is in fact a tremendous act of activism for the Kurdish language, which has long been suppressed by Turkish nationalist policies, as well as a testament to the written text as a living, ever-changing discourse. Through close observation and innovative cinematic technique, Kuryel and Yücel paint a moving, profound portrait composed of the destructive language politics in contemporary Turkey; the tenuous, confounding journey of the translator; and literature as archive. What results is a film that is not only a document of Nemir’s epic journey through the Joycean labyrinth, but a remarkable, intricate tracing of how the vast history and collective memory of language can find a home in a story, or in a mind.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): Aylin, the relationships between images and their communication of ideology has been a continuous subject in your work as a filmmaker and thinker. In this film, however, it is not the image which takes centre stage, but a text; how has your conception of visual dialectics transferred into the consideration of language as a social and ideological construct? Has making this film changed the way either of you think about the role language plays, or the way its public usage interacts with discrete individuals?

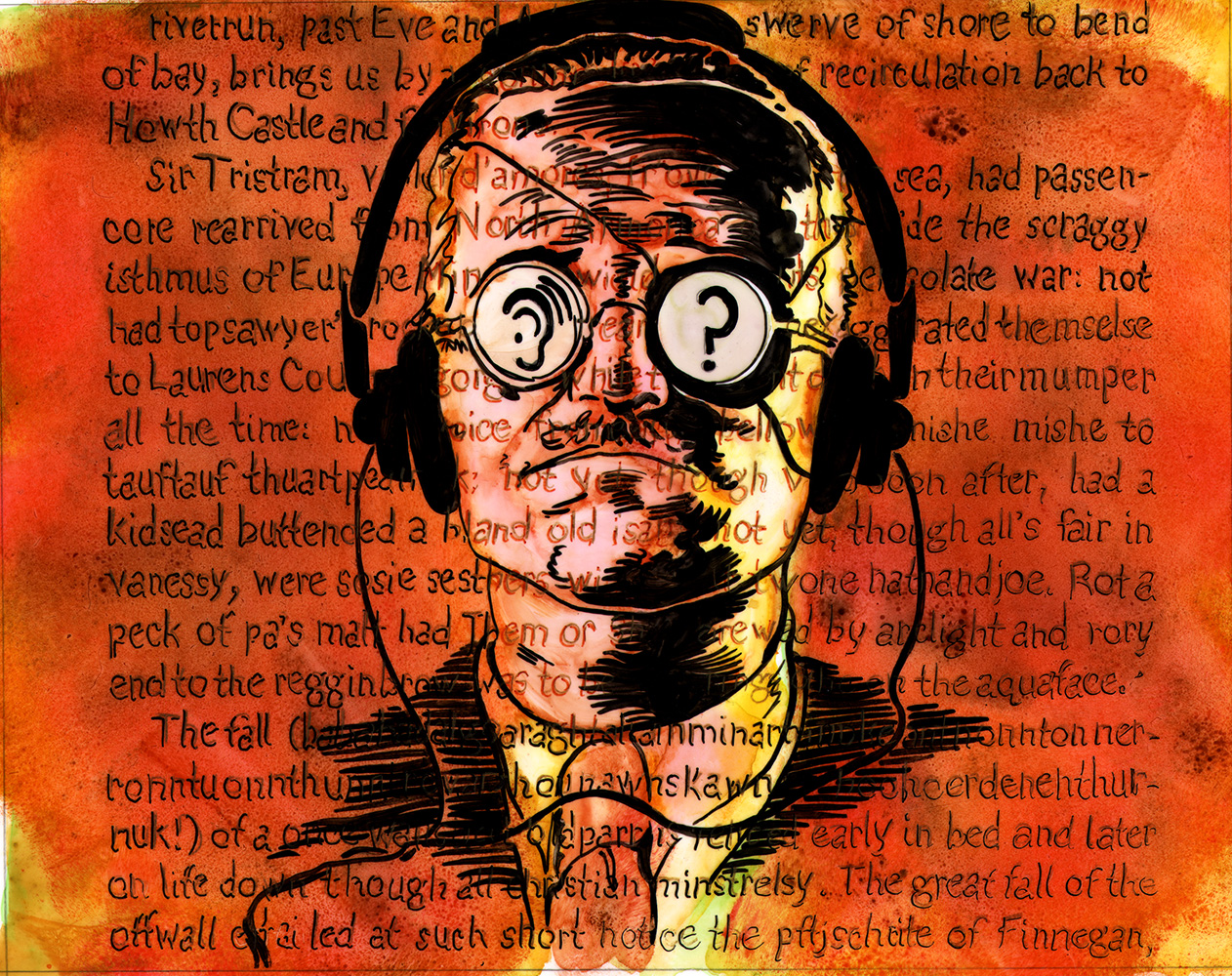

Aylin Kuryel (AK): One of the central questions that haunted us while making this film was indeed how to ‘translate’ the process of translating a text into images, how to make both Ulysses itself and Kawa’s translation of Ulysses speak in images. This is probably why we ended up structuring the documentary in chapters, like a book, with each chapter focusing on a different aspect of the process of translation. We wanted to approach the film as a text itself, making references to Ulysses, and edit it in a way that would allow the images to be ‘read’ in multiple ways.

We had the ‘speaking soap’ of Joyce in our mind while focusing on objects that surround Kawa during his translation process, the colours of Ulysses’s chapters while playing with the colours of the film, and so on. The language of the film needs to reflect—or at least allude to—the subject it follows. Therefore, apart from the references to Ulysses, we also wanted to use found footage (official propaganda material or visuals of Kurdish resistance, taken from Youtube and social media). A documentary that attempts to touch upon a long-lasting collective resistance (in this case, against the oppression of the Kurdish language) can consist of a collective of images too, captured in different periods, by different people and organizations, for different purposes. READ MORE…