Can Finnegans Wake be translated into another language? As the joke well-known amongst Joyceans goes, “Which language are you translating it from?”

If it is possible to translate Finnegans Wake, the next question might be: who on earth is willing and able to undertake such a task? Who even has the time to translate this work Joyce spent 17 years writing?

The Wake has been translated into French twice. Philippe Lavergne translated the book in the early 1980s, but unsatisfied with this edition, Hervé Michel has spent the last two decades working on a translation of his own.

Michel was born to French parents, in 1950s Morocco. He spent his youth “wandering across Europe, America, Africa and the Near East.” From 1979 until 1984 he lived in Casablanca, studying Arabic. Michel joined the French civil service in 1986 and eventually attended the Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA). With an annual acceptance rate of only 6%, ENA is an extremely elite graduate school for French government administrators and officials. After a decade of varied work ranging from finance to international relations, in 1996 Michel accepted a high-ranking position within the French Ministry of Defense.

In his spare time, Michel reads the Wake. He first encountered the book in 1980 and began translating the text in 1997. He has tried at various times to find a publisher for his translation, but the audience for Finnegans Wake translations is limited. In 2004 Michel decided to publish his translation as Veillée Pinouilles online, a format that allows him to make ongoing updates and revisions à la Leaves of Grass.

As Michel prepared to retire from his career in the civil service, he graciously took the time to speak with me about this longstanding fascination with the Wake. The interview was conducted over email, a format allowing for conversation as well as textual elucidation and analysis.

Derek Pyle (DP): How did you first get interested in Joyce?

Hervé Michel (HM): My interest first went to Finnegans Wake, not to James Joyce. By 1985, I had returned to Paris from a five-year sojourn in Morocco—a country where I happened to be born and raised from 1950 to 1962 and where I had returned with my newly-met wife Constance Hélène in 1980—where I had spent a jolly good time studying Arabic and reading the Qur’an. Back in Paris I felt compelled to go to the Galignani English bookshop on Rue de Rivoli to buy Finnegans Wake, on the back cover of which I discovered the man-in-the-street allure of James Joyce which was a sort of a shock. For me, Finnegans Wake was the Sacred Scripture of the Modern Era. I was not to be deceived by a text displaying all the phatic function I expected and smearing a thick semiotic matter, so I immediately felt the need to have it rendered in French.

DP: So you began with Finnegans Wake. Did you go the bookshop specifically seeking out the Wake? Or did it just one day catch your eye, while you were in the bookshop? Can you also explain a bit more what you mean that this was a text ”displaying all the phatic function… and smearing a thick semiotic matter”?

HM: Reference to James Joyce was paramount in the French literary critique between 1960 and 1980, people like Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, all drove me to consider Finnegans Wake as the nexus of the modern literary fabric, which I, with my gross ignorance of the finesse of the English language and of the encyclopedic richness of Joyce’s culture, took at first as the thick material somebody like Jackson Pollock smeared on his canvasses, but eventually I craved to emulate this latter Indian creation dance myself with the French language.

DP: Well, that’s an incredible cast of characters recommending the Wake! Tell me more about how that intellectual milieu shaped your own thinking and experiences during this time period.

HM: Well, it was the post May ‘68 period, a God-dead world begot by the 20th century. Revolution had been a god of death, “fixed in the principles that had it begun, it was finished”—to paraphrase Bonaparte at the 18th Brumaire coup—which left the individual bizarrely free and derelict at the same time, and most importantly, left his language clogged by the ruins of history and deception of culture, his nerves racked by the urgency of expressing the unmarketable.

So Joyce was felt to be a formidable example of the unreadable dream felt in the flesh of the fallen common son of Adam at a time when Waiting for Godot was the big cultural event.

An important line that led to Finnegans Wake is that it was read as a work of cultural decolonization from Britain in a period that witnessed the end of the colonial empire and the provincialization of French culture.

Neither Marxist, nor Freudian, the James Joyce Experience was to be for me a contrived way to elaborate on the basic intellectual needs of my post-modernist moment, by using a tool made known by the Situationist movement, détournement adulterated by William Burroughs cut-up, and para-Derridean deconstruction. Flow of conscience was to be ridden shapelessly.

DP: What an incredible frame of reference with which to be reading Finnegans Wake for the first time! Obviously all of this had a huge impact on you, intellectually and otherwise. How involved were at the time—were you, say, attending lectures by Lacan at the Place du Panthéon, or at the École Normale Supérieure with Derrida? Or else was your engagement more secondary, through reading texts?

HM: Not involved, no engagement. I dropped out of Sciences Po [the Institut d’études politiques in Paris] in 1973 following the Yippie slogan, “Turn on, tune in, drop out” and went through lengthy travels in Africa, America, Europe and the Near East, reading a hotch-potch of Internationale Situationniste, Dao De Jing, Sufism and Sophists. I then turned Timothy Leary’s slogan around when I made my “drop in” at the ENA (the prestigious Ecole Nationale d’Administration) in 1994. I became Administrateur civil at the Ministry of Defence. Such was my ennui at this post, that in 1997 I started my translation of Finnegans Wake the first draft of which I posted on the Internet seven years later in 2004.

DP: So let’s talk more about your translation of Finnegans Wake. What first inspired you to translate a work that so many consider un-translatable?

HM: I soon found that the only way for me to read it was to translate it. Since hardly any word does not require a dictionary, it is best to note the apparent meanings dug out in the process of reading, then make an arbitration during the second read through using the hints given by the word-by-word scouts of the book, for example the Annotations of McHugh and the FWEET database. A third step is then required to square the findings with the gloss of the text, seen as a narrative of sort, like Tyndall or Burgess, or as a feat of oneiric knowledge, like Bishop, or as a key to a sexual ciphering, like Solomon.

You have asked me about what I meant by semiotic mash: that is the thick material that James Joyce contrived and which I felt was so pleasant to drill. How could I have gotten through the book without carefully writing how the reading resonated in my own culture—that is in French, the language that conveys my basic references.

What happened with Finnegans Wake is that I enjoyed the result of a transposition of the semiotic material that it offered into French. Whatever the pertinence of my grasping of it may be, the pleasure was such that I endeavored the translation of all of this mash, because the effect of this mash is also related to it being the composition of a book—it is important that the translation be complete for its comprehension by the circle of its French-speaking readers.

DP: You say that the translation has to be complete in order to be understood, but I’m thinking about the questions of authorship, translating a work like the Wake. Is a translation of Finnegans Wake actually Finnegans Wake, or is it some new work, albeit one linguistically inspired by Joyce? In other words, how much of your translation is Joyce, and how much of it is your interpretative spin on the Wake?

HM: The interpreter is just that. Even if he (I) takes so much liberty as to make an adaptation, the creator (James Joyce) retains his eminent right on his work (Finnegans Wake), and the work adapted remains in his realm. Faust may be translated by Gérard de Nerval, Edgar Poe by Baudelaire or Mallarmé, and these translations are praised for their elegance and possibly their accuracy. The reader still gets access to the work, read by someone who says to him: “listen to how I think I could say what my access to the book’s culture allows me to understand in French.” No, the translator is not a traitor, the transposition into another language simply lays bare what happens in a particular reader’s mind. Whether the translator is weak or ill-informed, he makes a bad translation the way a weak ill-informed mind pertaining to the source culture of the work receives it, a bad reception can be seen in the same way that a bad translation is seen as a lying layer.

In short, everything in my translation is my interpretative spin, and it is nothing but an interpretation of a work of scriptural creation that is entirely Joyce’s.

That leads me to the question of the necessary completeness of the book. It is definitely my spin to see Finnegans Wake as an object of literature given as such by James Joyce. It means that any word, pun, sentence, paragraph is taken in a frame of pages, chapters, parts of a book with a definite, if abrupt, beginning, and a definite if evasive end. If you have to rebuild a labyrinth in your own park, you do not obliterate the dead ends and submit to the geometry.

DP: How did you approach translating the various multilingual puns and portmanteaus? How did you decide when to translate an individual word, and when to keep that word unchanged?

HM: Translating a pun is transposing a double—or maybe multiple—meaning word whose sound relates it to a number of meanings that in standard talk are related to different situations, contexts, or to another order or class of meaning. Joyce extends the possibilities of pun creation by adding plays with the orthography to hint to an even wider area of ambiguity.

The portmanteau word is not as much ambiguous as it is poetic, aggregating meaning in an un-syntactical way. It participates in la rencontre d’un parapluie et d’une machine à coudre sur une table de dissection [the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella], as the Compte de Lautréamont elaborated on his own suprareal literary operation, the same operation in which Joyce delights.

In either case, my rule is to translate the English elements or sounds and to leave other languages as they appear in the original. So the operation boils down to identifying the terms of the ambiguity by the way they could have meaning locally—that is to say at a given place in the text—and finding the French words that relate to them in an approximated way, to an analogous class of meaning. This strategy finds solutions more often than not.

One helpful factor is the ubiquity of French and Latin in the English language. If you consider the Japanese (Yanase’s and Miyata’s) and Chinese (Dai Congrong’s) translations [of Finnegans Wake], the former creates new semantic connections by playing by the specific potentialities of the writing system (Sino-Japanese weaving an intricate knot of meaning constituting an ideogram), while the translator of the latter concedes that she translates only a straightforward meaning of a given bit of sentence and drops the ambiguities keeping herself safe from word creation. Lavergne’s French translation has his particular way of skipping the language creation taboo by extending surrealistic description in correct French language in spite of Joyce’s dismissal of automatic writing. This shows how work is essential in our progress—the work of laying for ourselves the sand and stones of nostro cammino.

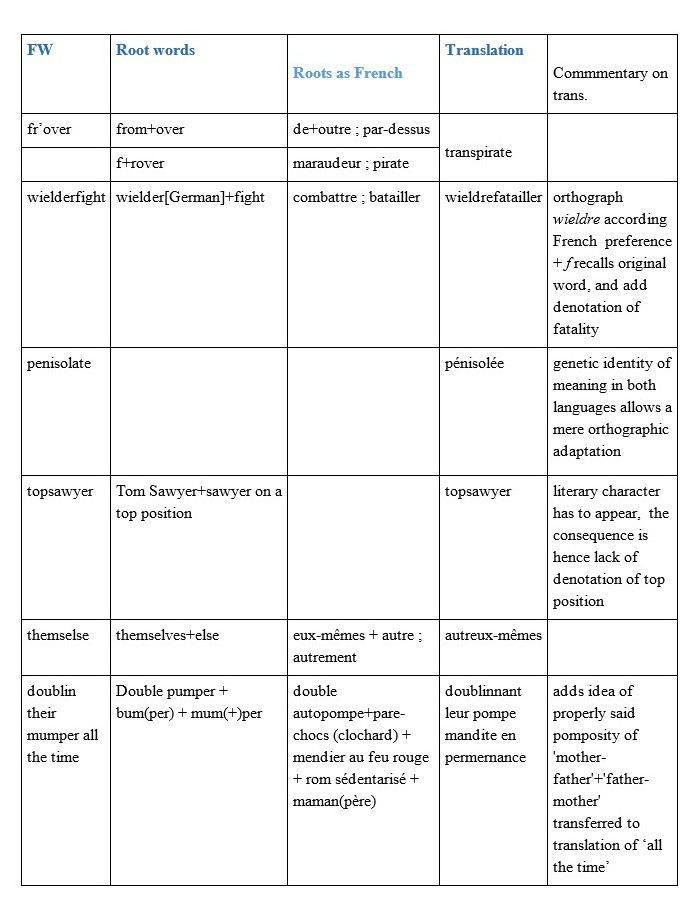

Yours is a nodal question that I would like to answer with a systematic answer, but that would require first setting parameters. In any case, here are a few examples of translations of words with multiple meanings excerpted from the second paragraph of Finnegans Wake:

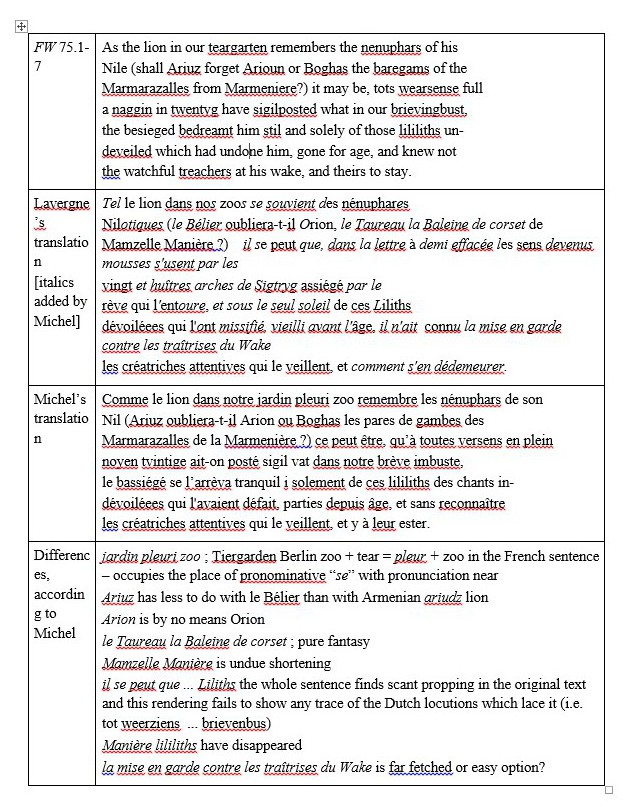

Sir Tristram, violer d’amores, fr’over the short sea, had passen-core rearrived from North Armorica on this side the scraggy isthmus of Europe Minor to wielderfight his penisolate war; nor had topsawyer’s rocks by the stream Oconee exaggerated themselse to Laurens County’s gorgios while they went doublin their mumper all the time… (FW 3.4-9)

Michel’s translation of FW 3.4-9, italics added by Michel for emphasis:

Sir Tristram, violer d’amores, transpirate la mer courte, était passencore réarrivé d’Armorique du Nord sur ce côté de l’isthme efflanqué d’Europe Mineure wieldrefatailler sa guerre pénisolée ; ni ne s’étaient les rochers de topsawyer sur le cours de l’Oconee exaggéré autreux-mêmes aux gorgioses du Comté de Laurens tandis qu’ils allaient doublinnant leur pompe mandite en permernance…

DP: Fascinating. Can you say more about how your French translation differs from Lavergne’s? Did you use his text at all while working on yours?

HM: The main difference, which makes it impossible to reconcile with a dispassionate evaluation of respective merits, is my biased [opinion]. Nevertheless, I would say that at the start I did not find great differences of perception in Lavergne’s translation of Finnegans Wake; his avant-propos can be described as “introverted writing, ostensibly turned towards the secret side of language,” as Roland Barthes said, the translation having to bring out the “tracking” aspect of this mocking scripture.

It was while performing the translation myself that I progressively lost the need for even consulting Lavergne’s translation. I found myself taking a rather literalist approach, wondering why, for example, on page 18.2 Meldundleize! is “translated” [by Lavergne] to Mild und leise ! This might be the correct quotation of Wagner in the original German, but it obliterates the fact that Joyce rendered it distorted in the text to his English-speaking readers.

My literalist ire grew so much as to dismiss the Lavergne translation altogether, not to say that it is unreadable or even not enjoyable, but it was of little use to me as anything but its own project. I would like to illustrate some of the problems I had to tackle. Take the first sentence of chapter four:

Mind you, Philippe Lavergne’s translation, published in 1978, received the 1993 Prix Langlois awarded by the Académie Française, and has been since reprinted, which testifies to its authority and success. Derrida notoriously remarked the shortcomings in Deux mots pour Joyce (about “he war” 258.12), but even he did not openly disavow [Lavergne’s translation].

Hence, translating has to be attempted over and over again, infusing in the receiver’s language the results of this demanding endeavor that is reading Finnegans Wake. Like the Qur’an says, “with hard thing comes easy thing”.

DP: Some translators of the Wake seek to make the book more accessible to readers in a new language, while other versions offer the English and translated texts side by side along with annotations and other notes—likely this kind of scholarly translation appeals only to a small academic crowd. Finnegans Wake is not exactly the world’s most read book, so I’m sure some other people just translate the Wake as a source of personal enjoyment, without much regard for any potential audience. How would you describe your own motivations? Once completed, what was your goal for the text?

HM: My personal enjoyment, which is enduring, has much regard to an ideal readership my goal is an ideal conversation until and about the end of our lives, with Finnegans Wake as a vicar (meaning the commodious way). But, it does not really work like that, because translation is far less a mystery than a puzzle, a game played at very scarce gatherings. Academic translations have the merit of being organized, as well as watching the gates of literary value, so the translator can safely play, within their circles, with the gist of the pun, while outside these circles, it is just one enormous hoax.

Hence this healthy meditation on the coincidentia oppositorum that the translation brought about. Though this wasn’t exactly its initial goal, it led me now to follow the advice of Roland Barthes: “lis tes ratures!” [read what you’ve erased] (my translation) ’Cause it won’t make you rot! Yes, I am 65 and retiring this very month and my goal now is health more than wealth.

DP: For many, Finnegans Wake is a daunting book. Any advice readers either approaching the English version, or your translation, for the first time?

HM: I would advise that a reader approach Finnegans Wake like a work of art—a composition of sounds and colors, music and painting, to be listened to and looked at not like an abstract, but like the Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch, painted by Georges Braque, with music by Olivier Messiaen, words by James Joyce. And these words go beyond the surface, because it is a palimpsest, to which you will be able to return so many times to enjoy such and such detail, sometimes you may feel it makes you contemplate the ineffable; still it is a gigantic hoax devised with utmost care and the finest scholarship that you should see if you have eyes for yes.

Derek Pyle is director of Waywords and Meansigns, an international project setting James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake to music. With readers and musicians from around the world, all audio is distributed freely. As a musician and otherwise, Derek‘s style is loose and expansive.

*****

Read More Interviews About Translation:

- Zsuzanna Gahse’s Europe: Like Her New Book, It’s a Collection

- Meet the Publisher: Juliet Mabey on Oneworld’s Roots and the Business of Publishing Translations

- Spotlight on Indian Languages: Part VI