Much of my fascination with contemporary Afrofuturism revolves around studying the ways in which Black artists in the field are utilizing the Internet to complicate the idea of ‘alien space.’ Afrofuturism necessarily points to an-other space—traditionally, outer space—as the destination point for the Black human-being, who, being so totally extradited from Earthly society, requires a more total severance in form of a physical migration. The cosmos has, for decades prior, served as the primary landing space for the Black alien migrant, but in recent years, the Internet has made its way to the forefront of the Afrofuture. Relative to cosmic space, the Internet has served as a perhaps closer and seemingly just-as-expansive alternate realm to which to escape. And in fact, the ‘proximity’ of the Internet calls into question whether ‘escape’ is really the dominant motion; rather than, for example, the motion of transformation. (I don’t think that anyone doubts anymore that the relationship between meatspace and cyberspace is mutually mutative.) The contemporary fugitive as shapeshifter and space-shifter.

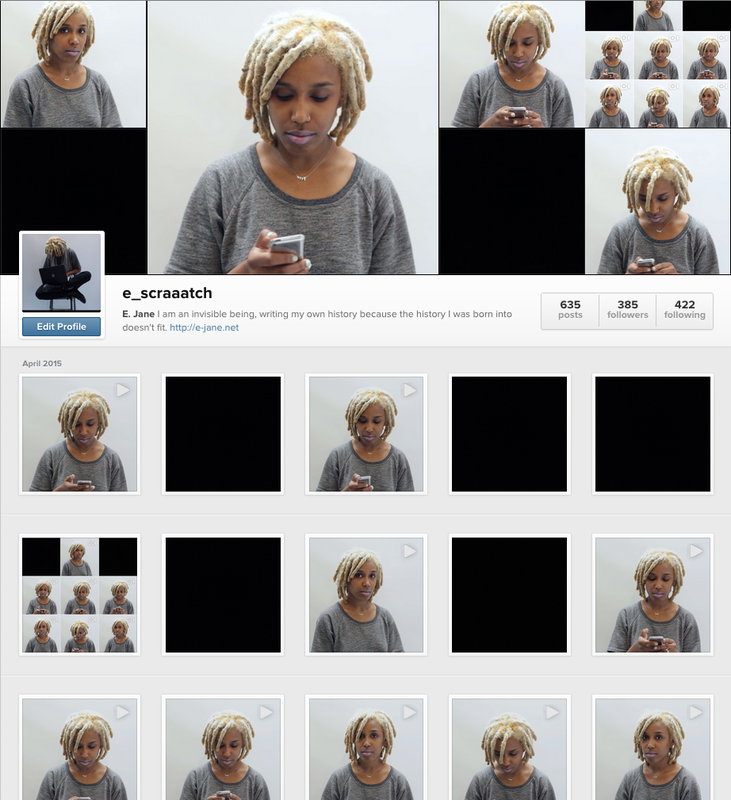

E. Jane is one such artist who has made the Internet a primary medium. Creating cyber-installations across multiple social media platforms, as well as video, and sound-based works, E. Jane’s work is a seminal voice in the growing field of Internet-based Afrofuturism. Not to mention, E. is also one half of the Philadelphia-based sound-duo named SCRAAATCH—the other half being their partner, chukwumaa. Notably, the duo recently appeared The Fader in a feature titled, “The Voices Disrupting White Supremacy Through Sound.”

E. and I met in cyberspace to chat about their most recent work. We began with a quote from Toni Morrison, whom E. had spent the day reading.

***

For many are the pleasant forms which exist in

numerous sins,

and incontinencies,

and disgraceful passions

and fleeting pleasures,

which (men) embrace until they become

sober

and go up to their resting place.

And they will find me there,

and they will live,

and they will not die again.

– Toni Morrison, Paradise

E. Jane: I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of a place where you can’t die in relation to the Internet. This [Toni Morrison] line really struck me after Christian Taylor’s death because we found his Twitter account and he was so expressive. And it feels like a digital grave. I kinda included it in a track I made last month. A sort of dirge I made for him and the other young Black men and women and trans people that have been killed lately.

Anaïs Duplan: In other interviews of yours, you’ve talked about protecting the Black female body by storing it online and about how the existence of place where one can’t die—namely, the Internet—feels like a kind of protection. But, to me, the Internet also feels like a dangerous place for Black bodies. I think of pictures of dead Black bodies from online news sources that are distributed so carelessly.

EJ: Totally. The Internet can be a triggering space. But the Internet is way more malleable than meatspace. I can’t curve a bullet but I can change my settings/friends/interests so that I never see a Black body lying in the street again. I can ask that my friends provide trigger warnings (which I think we’re all being better about—at least in the online communities I am a part of). So in a way, the danger can be mitigated here in a way it really can’t in meatspace.

AD: Has your relationship to the Internet changed over time? Have you always been aware of it as a safe space? EJ: I’ve been on the Internet most of my life. Though this is the most intentional relationship I’ve had with the Internet. Although I’ve always felt the Internet to be a safer space where I could shift very easily, it’s never been as obviously important to me as a solution. My work is deeply performance-based and I would always get the critique that I needed to go “out into the world” with the performance but that always felt so violent for me. I’ve done a few performances in meatspace but some of my gestures require an extreme amount of invulnerability or safety. I think I realized that the Internet was that sort of public space for me last year when I did this piece called, “The Artist Sits in Comfort” where I really just sat online and pressed record in a space I considered “safe” as a compromise with the outside world. That piece was my first attempt to choose the Internet as my safe space in my work. Still, growing up queer, the Internet was always the space where I could mostly engage all of my selves. the artist sits in comfort [45 min clip] from E. Jane on Vimeo. AD: One of the things I really appreciated about that piece was that I, too, could feel comfortable. Meatspace can feel like a constant compromise—trying to feel comfortable while being sure to not make others uncomfortable. Especially as a Black female-bodied person, even just my comfort is sometimes responded to by others as though it were threatening. Does the safety of your viewership ever become a concern for you? EJ: Yes and no. Worrying about the safety of the viewer in relation to a work of art can be a trap sometimes. I don’t believe in making work that would do harm to someone else, unless that person feels harmed when they experience something foreign to them. I’ve made people uncomfortable before with my work. Maybe it made no sense to them or it didn’t relate to their view of the world. And maybe those feelings made them feel fragile or less safe and maybe that means they’re experiencing new information and it’s okay. But I’d never make anything to intentionally trigger someone else. That’s just not what we need right now in culture. AD: It might almost betray the safety of the work itself if you were to try to protect your viewers from discomfort. Just now, when you talked about creating work that doesn’t necessarily relate to your audience’s views of the world, I thought of your response to a question I asked you a while ago, about how the world ends. You said:

It doesn’t. I’m mostly an afro-absurdist, interested in speculative fiction and the future we currently exist in. When the world ends, another world will be constructed, perhaps two or three worlds. New life will form on those worlds and everything will start back up again. Or everything will end when the sun explodes (it’s a star) and all sentient beings will cease to exist and consciousness will end. It could go either way.

EJ: My relationship to absurdism starts with Camus and Jean Genet. I was really into Waiting for Godot and The Balcony in undergrad and this notion of the absurd world. Right now I feel that our world is very absurd or illogical and searching for logic can lead to a type of depression. There are so many instances that make no ‘sense’ except when you abandon logic for the absurd logic of the world you’re in. With that being said, I sometimes choose the logic that gives my life the most meaning. But also I’m interested in what science thinks started everything and will end everything and how even now, some people are arguing that the Big Bang may never have happened. The laws of physics seem to make sense for me and the notion that energy can neither be created nor destroyed and if that’s the case, it’s nice to imagine that everything never truly ends, we never truly die, etc. Everything else is too depressing and can lead to a wormhole of dark thoughts, such as if the world will end, and all of this will one day cease to exist let alone matter, why are we making? Absurdism tells us to make our own meaning and logic to keep us going because the search for some cosmic ‘sense’ will fail us.

#mood A photo posted by E. Jane™ (@e_scraaatch) on

EJ (continued): I’m thinking of Camus’s essay on absurdity and suicide in particular. While he says a lot about science and logic and meaning, what most interests me is his observation that the search for meaning and god lead men to suicide. Absurdism is the answer to that quest. I think he is thinking about the alienated worker and the redundancy of everyday life and this need for meaning to give life purpose. He also talks about how human-centric our world views are.

AD: I was struck by what you said about the relation between the logic of everyday life and a perhaps more absurd logic which is more true, at least for the individual. If, for example, the anthropocentric approach to a global issue doesn’t make intuitive sense to someone, there are many widely shared societal beliefs which become immediately less available.

EJ: A good quote from the essay:

The truism “All thought is anthropomorphic” has no other meaning. Likewise, the mind that aims to understand reality can consider itself satisfied only by reducing it to terms of thought. If man realized that the universe like him can love and suffer, he would be reconciled. If thought discovered in the shimmering mirrors of phenomena eternal relations capable of summing them up and summing themselves up in a single principle, then would be seen an intellectual joy of which the myth of the blessed would be but a ridiculous imitation. That nostalgia for unity, that appetite for the absolute illustrates the essential impulse of the human drama. But the fact of that nostalgia’s existence does not imply that it is to be immediately satisfied. For if, bridging the gulf that separates desire from conquest, we assert with Parmenides the reality of the One (whatever it may be), we fall into the ridiculous contradiction of a mind that asserts total unity and proves by its very assertion its own difference and the diversity it claimed to resolve. This other vicious circle is enough to stifle our hopes.

AD: What do you make of “the myth of the blessed”?

EJ: I was raised Baptist. The Baptist religion seemed to always teach that god would fix everything in due time and that baptized people would always be blessed. I don’t believe that though. I think privilege determines who receives what one could consider “blessings.” I want to believe you can work towards certain privileges or that hard work can grant privilege but I think we live in a fucked world where some people will never get what they pray for no matter how hard they pray or how blessed they tell themselves they are. My mom prayed not to go to prison and still ended up in prison.

AD: The very idea of blessedness makes it all the more difficult to reconcile the apparent lack of control that a lot of us have over our lives. In particular, the lack of control to stop ourselves from being controlled, except by existing in spaces where we’re a bit more impervious. I run into this question of absurdity a lot when I try to understand the forces that create helplessness, in my life and work, etc., and it seems that seeking comfort might also, in a way, cause me discomfort because it forces me to continually confront the existence of things that are trying to control me. I guess I’m circling back to where we were before, about comfort. What do you think is the relation of comfort and discomfort, control, safety, helplessness? And how do you deal with the inherent dangers (to yourself) of your work?

EJ: I try not to think about myself very much in a way, except for how my body relates to other bodies. I guess I’m free-falling a little in relation to any danger I’m in because of my work, though I feel there are few. I keep myself fairly isolated in meatspace in a way that makes me feel secure and I think of the people that cannot attain any security. Developing a sense of autonomy within my practice has left me feeling very secure. I know where my body goes and what happens to it and I determine that.

*****

Anaïs Duplan‘s writing has appeared in Hyperallergic, [PANK], Birdfeast, Phantom Limb, and other publications. She is a head curator at The Spacesuits and an MFA candidate at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Read More from Interviews: