For my latest event as the Austrian Cultural Forum London’s guest literary curator, I commissioned and curated work for an exhibition presenting multiple translations of a short story by Austrian author Anna Weidenholzer in forms including sound, ceramics, textiles, video, sculpture, photography, text, and even tattoo designs and recipes. A reading and performance event in the ACF’s Salon celebrated and closed the exhibition this week and let the audience all be translators for an evening.

The incredibly affecting short story “Sessel und Sätze” (“Chairs and Sentences”) from Anna Weidenholzer’s collection Der Platz des Hundes (Where the Dog Sits) follows aging school caretaker Ferdinand Felser’s preoccupations with his passive position in the world. Having been mocked as a schoolboy by pupils and teachers for his dialect—and by his parents for trying to change it—Ferdinand is now secretly learning nine languages in his office and is troubled by the climate of xenophobia surrounding him at work, in the news, and among close friends. You can read the story tomorrow on the Asymptote blog.

Posing as a metaphor for the multiplicity of possible translations of any story, the exhibition on display in the ACF’s gallery encouraged the visitor to see how each “translation” altered and added to their reading of the story (which they also read in translation) or how the exhibition could be one multifaceted translation. It considered a translation as a personal reading, extension, destruction or an attempt at honing into an essence of the original text by a “translator,” and also explored the fallibility/adaptability of linguistic translation by further experimenting with alternative translations.

The dozen practitioners I commissioned for the exhibition didn’t find their task as puzzling as you might initially think. They were all used to translating in a sense: having to imbue their work with what they wished to communicate, transforming an idea from one form into another. We’re used to seeing film adaptations of books, a director creating a play from a written text, a poem written after another poem—and translation is arguably a similarly creative and individual process where one story is transmitted through the “voice” and “language” of another. They also all immediately got why this story deserved to have so much time spent on it and why its message should be translated now.

Illustrator and ceramicist Sophie Alda, and textile and surface designer Lucy Anstey both had the task of turning the story into an object: ceramic wares and an item of clothing respectively. In Alda’s piece, a round black dish was the platform for a water jug and a clutch of giant ceramic straws. “It is important to define a language you are going to translate into. Ceramics, like spoken languages, are ubiquitous,” Alda explains. “Ceramics do not generally inhabit a favourable position in the hierarchy of objects. Their history is primarily based in function. I wanted these objects to have purpose and for the purpose to tell the story. What strikes me is the inconclusiveness of Ferdinand’s actions; uncomfortable feelings are easy to worry about but harder to address.” Anstey designed and made a utilitarian work jacket, something she could imagine Ferdinand wearing. “I wanted to make something practical and familiar in design that evoked the strong themes I picked up from the text,” she sets out. “The abstract repeat is constituted of layers of muted washed out blues and dusty flecks, as well as reverberant linear forms representing the conflicting repetitious thoughts, the ‘mental static,’ the Wollmaus in Ferdinand’s head.”

A clutch of the exhibitors harnessed the static and moving image. Tattoo artist Martha Ellen Smith drew a tattoo flash sheet for the exhibition encapsulating the story in a series of images. “I approached this project in the same way as I do in my own practice,” says Smith. “I decided to focus on an element of the story rather than translating it as a whole. The theme that really stood out to me was the simple idea of the caretaker’s want for a better life. Inside the TV, mop bucket, water spill, you could see his hopes and aspirations, but the cigarette butt, coffee cup, stack of chairs mocked his desire for a better education.” Maria Tedemalm, a filmmaker and animator, focused on the mood of the story’s spaces, creating a looping animation where chairs stack and unstack themselves, all the while accompanied by a blue, flickering void.

Artist and writer Lillian Wilkie’s installation allowed the audience to take away prints and used the seven concealed notebooks in the story as it’s framework. Consisting of seven piles of photographic reproductions presented on a Turkish mat, it was a bold gesture, as if you could take home something out of reach in the story itself. Photographer and documentary filmmaker Emma Charles exhibited a series of photographs. “Some of the images can be read as an abstract interpretation, whereas others could be scenes through the eyes of the protagonist,” she explains. “I felt there was an ambiguity here—was [ignoring xenophobic statements] an act of defiance through passivity or just indifference?”

Sound artist Rachael Finney created an infinite sound piece, manipulating her voice reading different foreign-language phrases found in the story which disintegrate over time through playing the tape within the kind of language-learning style cassette player you would have had at school. She explains that, “although one of the story’s central themes is language and communication there are only a few moments where the protagonist’s voice is directly referred to, including the words and phrases Ferdinand articulates incorrectly—vocal glitches—and the phrases he is attempting to learn in order to communicate to students. I have attempted to learn how to say the phrases he learnt for the students—these include Turkish, Albanian and Serbian.”

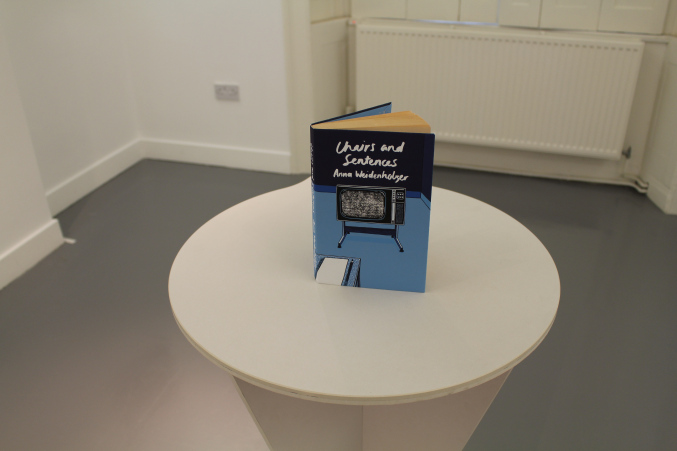

The exhibition also explored persuasive paratextual elements that influence the reading of books, such as covers, blurbs, and book reviews, which can also be seen as a form of translation; they function as abridged, mirroring versions of the text. Texts are never floating in a void without context, but are rather surrounded by other stories and other materials, like illustrations and blurbs, and are often preceded by reviews. Not to mention the reader’s prior knowledge, memories, experience and personality. All of these things form “the text.” Illustrator and artist Barbie Lawrie was commissioned to create a book cover for a potential translation, while Agatha Frischmuth wrote a review of the story in itself and as a part of a larger collection. Lawrie focused on Ferdinand’s emotional state of mind for her blue cover depicting Ferdinand’s living room: “The static television represents his busy state of mind, the white noise in his head, the constant barrage of xenophobic thoughts freely shared with him that he is unable to respond to.” Frischmuth concluded in her “intuitive” review that Ferdinand is also a translator: “Not because he knows foreign words, but because he desires the opportunity to convey something to someone.”

Renowned bilingual Austrian-American poet Ann Cotten (whose poems have previously appeared in Asymptote) and PhD candidate Laura Tenschert both created forms of intralingual and/or text-based translations. Cotten wrote a German-language poem encapsulating the text from her point of view. She stated in her translator’s note that the story was primarily Weidenholzer’s study of the proletarian male and Ferdinand’s “mild interest in the world.”

Tenschert created two pieces: the first was an alternative German to English translation of the first three paragraphs of Weidenholzer’s story into an American-English and American context where “Ferdinand” becomes “Fred,” the other a one-page adaptation of the story into a screenplay. “By translating Weidenholzer’s story into a different cultural context, and losing almost all of the ‘Austrian’ elements in the process,” Tenschert explains, “I’ve tried to retain what I could of the key points by envisioning the situations that would lead to and shape the character’s experiences.”

For the reading event American musician Robert Chandler read Tenschert’s brief translation before she explained the various changes she made: the wedding scene on TV is replaced by cowboys hunting Native Americans, the Turks of the original story have been replaced by Mexicans, for instance, the voice coming straight from Donald Trump’s Presidential campaign. The central performance of the night was by PhD candidate and avid cook Rebecca May Johnson, who wrote a recipe laying out the cross-cultural powers of rice pudding or Milchreis for the exhibition. “When thinking about what recipe I want to come up with, I always imagine how I want the resulting eating to make me feel,” she explains. “These feelings, along with specific elements of context—Germanness, Turkishness—were what I tried to convey through my translation of the story into a recipe. I think our bodies can be better diplomats and translators than our minds, realizing and becoming fluent in the joy of difference, long before we are intellectually ready to engage in it.”

Johnson cooked two recipes for the closing event for the guests’ enjoyment, but also for the audience to translate their eating experience into text. This resulted in crafted poems, childhood memories, witty ditties and wondrous fragments. Anna Weidenholzer and I opened the evening by giving a simultaneous reading of the story, taking it in turns to read it paragraph by paragraph in our native languages with my translation being projected beside us.

I can perhaps only weigh the success of the exhibition and the event on the “eureka” responses I heard from the visitors who had never before even considered translation as a creative art . . . and Anna Weidenholzer’s elation; she went so far as to say that it had made her completely revaluate her original story. The original is dead. Long live the original.

*****

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator from German, editor and curator based in London. She is The Quietus’ columnist for literature in translation and her articles and reviews have been published by the TLS, Huck and Modern Poetry in Translation. Her own short fiction has appeared in Structo and TEAM and she has been shortlisted for the Melita Hume Poetry Prize 2015. She edits the Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt, is former acting editor of New Books in German and is guest literary curator for the Austrian Cultural Forum London throughout 2015. She has translated prose and poetry for Bloomsbury, PEN International and the Goethe-Institut and is currently translating Nicotine by Gregor Hens for Fitzcarraldo Editions.

You can read about how she previously turned the ACF salon into the set of a murder mystery complete with torture chamber, forest and detective’s office, and invited British and Austrian authors to write together about London for a week (the results of which will be published by the ACF as a pamphlet early next year) in the latest issue of New Books in German.

Read more from German: