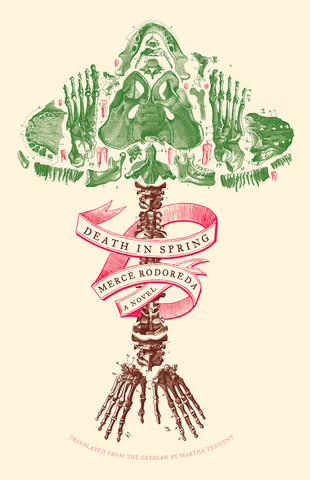

Mercè Rodoreda, Death in Spring (Open Letter, September 2015). Tr. from the Catalan by Martha Tennant—Review by Ellen Jones, Criticism Editor

Martha Tennant’s translation of Death in Spring, the (posthumously published) final novel by Mercè Rodoreda, is republished in paperback this month by Open Letter, having been long out of print. Written while in exile from Franco’s Spain during the Civil War, the novel is considered Rodoreda’s most accomplished work, and can be read as an allegory of a repressive regime.

Told through the eyes of a nameless boy who seems perpetually on the cusp of manhood, the novel recounts the cruel, bewildering traditions of a village community constantly under threat of being washed away by the river that runs underneath it. The villagers’ brutalism is bizarre and often casual—they pour cement down people’s throats as they lie dying to prevent their souls from escaping, then bury them in hollowed out trees. A thief is imprisoned in a tiny cage until he begins to behave like an animal; children are locked in cupboards until they half-suffocate; and every year a young man is forced to swim underneath the village and endure inevitable mutilation or death.

The novel reflects on on the dangers of blind adherence to tradition and on our ability to reason ourselves into committing ritual cruelties. The ‘soulless’ dead—namely, those who die unexpectedly—are buried in unmarked graves at the foot of the mountain, in ‘the cemetery of the uncemented dead.’ It is said that ‘the faceless men’ who emerge ravaged from the river are reborn and will be ‘always at peace,’ but they are ostracised along with others who suffer physical deformities, and are forced to sweep the streets at night.

The villagers in Death in Spring seek to eradicate any powerful desire, but are especially afraid of female sexuality—pregnant women must walk around blindfolded so they do not lust after men whose features will be imprinted on their unborn children. This is made all the more sinister for being overlain by imagery bursting with color and life: conventional symbolism is inverted so that trees digest rotting bodies, wisteria slowly strangles buildings, birds are in mourning, and springtime verdure is poisonous.

Amid these dark customs, the nameless narrator finds a playmate in his equally child-like stepmother, in the graveyard and at the bottom of a well, while time seems to stretch and fold strangely. In Tennant’s translation, Rodoreda’s prose is astonishingly lyrical, rendering this novel equal parts disturbing and beautiful.

***

Joseph Roth, The Hotel Years (New Directions, September 2015 paperback). Tr. from the German by Michael Hofmann—Review by Hannah Berk, English Social Media Manager

An immediate pleasure of Joseph Roth’s writing is its peppering of idiosyncrasies. In Samara, a goat blocks his hotel door. A barge hauler along the Volga boasts of his talent for downing three pumpkins in a 45-minute span. The Hotel Years, a newly released series of Roth’s interwar period feuilletons, is a great contribution to the collective imaginary of a Europe in tumult.

A self-professed “hotel patriot,” Roth’s loyalties and bouts of nostalgia are associated with travel itself, with motion and manifestations of cosmopolitanism amidst tense nationalistic divisions. To strike at a historical moment characterized by paranoias, apathies, and allegiances by turns blurred and polarized, he employs the particular, benefitting from sharp descriptions of people, landscapes, and small moments. Two gypsy girls walking on a windy day look “like two wandering flags;” Russian trains don’t merely whistle, but “howl like ship’s sirens,” instead.

Roth has little flare for large-scale drama. His vignette on interviewing the controversial Albanian president Ahmed Zogu contains neither action nor a single direct quote. But he delights in peculiarities that catch in his spectator’s skein, shining most of all in his speculations on the lives of hotel staff and his meditations on the minutia of streets in springtime.

These journalism-personal essay hybrids, originally printed in German papers, are loosely ordered by geography and chronology here. Michael Hofmann, the book’s brilliant editor and translator, appears to have deployed Roth’s own haphazard methodology: “It involved repeatedly going through the three blue non-fiction volumes and seeing what stuck, what went with what, what lived, what moved,” Hofmann writes in his introduction. “There is no duty, no mission, no set subject, no period, no place; I could just please myself.”

What stuck out for Hofmann has stuck with me. Roth’s slim volume is a deliberately and beautifully fragmented depiction of transitory Europe in all its extraordinary everyday mundanity.

***

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, A Cat, A Man, and Two Women (New Directions, September 2015). Tr. from the Japanese by Paul McCarthy—review by Alice Inggs, Editor-at-large South Africa

Cat protagonists are not uncommon in modern Japanese literature. Natsume Soseki’s I Am a Cat (Wagahai wa Neko de Aru), Hiraide Takashi’s The Guest Cat (Neko no Kyaku), and Kanai Mieko’s Oh, Tama! (Tama ya) are all well-loved stories in which felines feature in central roles. But Lily, the tortoiseshell in popular author Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s A Cat, a Man, and Two Women (Neko to Shōzō to Futari no Onna), is perhaps the most well-known of the litter.

Something of a literary stray, A Cat, a Man, and Two Women was originally released in 1936, translated in the early 1990s, out-of-print for a number of years, and now reissued as paperback by New Directions. It combines the title novella and two shorter pieces. The latter are “The Little Kingdom”—about a teacher effectively submitting to his students— and “Professor Rado”, the story of an aging man with a foot fetish (a favorite Tanizaki theme). But these two shorter pieces feel like more of an addendum to the novella, showing off Tanizaki’s considerable skill at simplifying complex human nature and effectively ushering in the reader as an eavesdropper on the often surprising private lives and thoughts of everyday people.

Tanizaki’s primary story is—as the title indicates—about a cat (Lily), a man (Shozo) and two women (Shinako and Fukuko). Shinako is Shozo’s first wife, Fukuko her younger replacement. Despite being jealous of Lily during their marriage, Shinako pleads with Shozo to give Lily to her, explaining that she “Didn’t take so much as a broken teacup away” when the pair split up. When Shozo puts her off, Shinako secretly writes to Fukuko.

“Do be careful, Fukuko dear,” Shinako warms, “Don’t think ‘Oh, it’s just a cat,’ or you may find yourself losing out to it in the end.” Everyone loses out to Lily, whose cool indifference stokes the tempers and jealousies of the three humans.

Lily is “an elegant Western breed”. But, as Japanese aphorist Saitō Ryokuu claimed: “elegance is frigid”. While Shozo, Shinako and Fukuko vie for each other’s attention (and the attention of the cat), Lily remains aloof and inscrutable.

This is perhaps the central idea of Tanizaki’s novella: Shozo, Shinako and Fukuku – and even Shozo’s scheming mother, O-rin—have little to distract themselves but each other. Their lives are routine, mapped out; whereas Lily is free to do as she pleases. The fact that her thoughts are impenetrable to the humans drives them to want to possess her—she becomes a stand-in for the lack they feel.

The play of light and dark that Tanizaki outlines in his essay on Japanese aesthetics, “In Praise of Shadows”, is also evident: Lily’s airy unattainability acts as a foil for the dim interiors of the human protagonists whose motives are often obscure, even to themselves. Paul McCarthy’s polished translation loses none of subtlety of the original, retaining both Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s linguistic wit and skill at sketching shrewd, unidealised depictions of traditional Japanese domesticity.

***

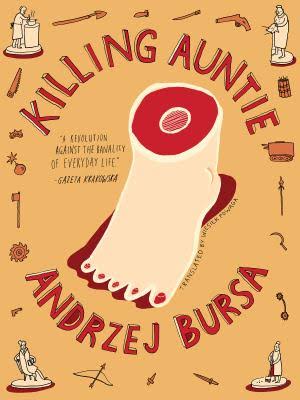

Andrej Bursa, Killing Auntie (New Vessel Press, September 2015). Tr. from the Polish by Wiesiek Powaga—review by Beatrice Smigasiewicz, Editor-at-Large Poland

Jurek, the twenty-year-old protagonist of Andrzej Bursa’s book, Killing Auntie (New Vessel Press, 2015) confesses to an excited priest that he committed a murder. When auntie’s murder takes place, it’s a surprise, but already an afterthought. The problem that preoccupies the narrator—and most of the novella—is not the problem of guilt that comes with feeling responsible for an action, but a problem of evidence, a problem of the body.

Jurek is an embodiment of a quintessential youth. A university student driven by whims, if anything happens to him, it happens by accident, by his stumbling into it (and not by some force of his intention). Jurek’s only goals, before the disposing of auntie’s body becomes his prime preoccupation, are his walks around town. The book is full of passages of aimless heading out, of leaving the house, walking to this or that location, the places themselves don’t seem to matter. In these lingering passages, Bursa’s Jurek makes, or doesn’t make, decisions—to go to the fountain or the movies, or to get a drink to talk to a girl. Until auntie’s death, he is ambivalent about things that are supposed to give life meaning: school… church. And although it’s that very ambivalence and blind groping for things to do, for goals that is at the root of what could be the profile of cold killer, what’s interesting about Bursa’s book is that he is careful to refrain from moralizing.

“To all who once stood terrified before the dead perspective of their youth,” Bursa writes on the dedication page, like homage to youth. Having come of age at a time when Soviet narratives of personal transformation by hard work, tractors and a grand finale set to the glow of orange-yellow sun with a girl hanging on the arm of a rising proletarian populated the bookstores. The challenge for Bursa was about showing the freedom to be young, and lost, like his narrator. For Bursa who was no older than twenty-five at the time he wrote Killing Auntie, the work is as much about the author’s own youth as it is about wrestling with the body of the tired middle-aged caring but oppressive auntie of literature who dead or alive he cannot do with or without.

In the preface, translator, Wiesiek Powaga included Bursa’s telling poem, “Thanksgiving Prayer (with grudge).” The poem is less of a poem than a farcical challenge, a kind of finger up a nose in the face of Polish poetry.

You didn’t make me a stutterer a gimp a midget epileptic hermaphrodite a horse moss or something from the flora or fauna

Thank you O Lord

But why did you make me a Pole?

To the romantic temperament that characterizes most of what we abroad know of contemporary Polish literature (Adam Mickiewicz, Czeslaw Milosz or Witold Gombrowicz) is the place to wrestle with big ideas in capital letters: Nation, State, Identity, and Moral Responsibility. At the time Bursa was writing, that was the job of Polish literature— to house a tradition, to inspire national resistance and national character against oppression. Bursa’s dead body grounds Jurek and gives shape to his life, but that romantic temperament is like a body he’s trying to get rid of.

Bursa’s energy is contagious. He was in his early twenties when he became a well-know poet and journalist with a following. He promoted writers who would later become some of the most important new voices in Polish literature. When he died at twenty-five, he was already a legend, immortalized in Stanislaw Czycz’s popular novella, And.

Killing Auntie was published posthumously, when it was discovered among drafts Bursa left in his drawer. It was a breath of fresh air and a bold rebellion against traditions in Polish literature. Bursa’s translator, Powaga, writes in the introduction to Bursa’s collected works where Killing Auntie first appeared: “I first read Bursa when I was seventeen, a long-haired rebel in a school run according to the drab rules of ‘mature socialism’ in 1970s Poland, and immediately felt I had found a kindred spirit.”

The book is just as fresh now as it was then.

*****