Read all posts in Mahmud Rahman’s investigation here.

In the early 20th century and into the first decades of independent India, there were a small number of translations into English. Across language boundaries, Indians read writers like Tagore, Sarat Chandra, and Premchand. Though the translations were often clunky, these books played a role in building a sense of India as a nation.

Initially there were a handful of publishers who published translations from a few Indian languages into English. Quality translations came from one or two individuals, such as the writer A.K. Ramanujan. Rita Kothari in her book Translating India includes this telling quote: “Prabhakar Machwe, secretary of the Sahitya Akademi in the seventies complained that, ‘even after 25 years, we have not been able to develop a team of ten good, competent translators of Indian languages into English.’”

Things began to turn by the late 1980s.

In 1988, Katha, an NGO dedicated to encouraging reading, was launched by Geeta Dharmarajan and began publishing stories in translation, eventually publishing from 21 Indian languages. Their effort reflected the work of over 600 writers and translators. This year Katha teamed up with Britannica to offer their translations electronically.

Initiated by the editor Mini Krishnan and funded by a grant from the A.R. Educational Trust, Macmillan launched the Modern Indian Novels in Translation series. Krishnan also produced the Dalit writing in translation series that published Bama’s memoir Karukku.

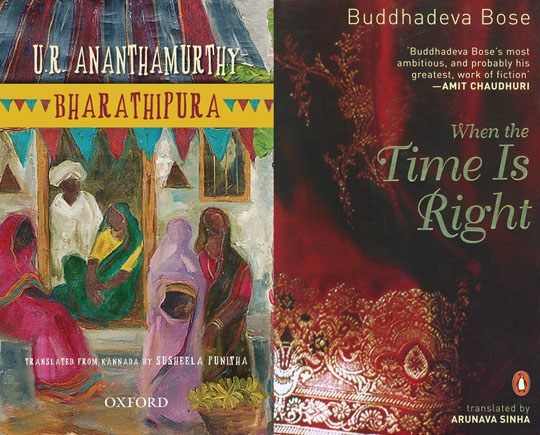

Besides Macmillan, other educational publishers, Oxford and Orient Longman, developed new initiatives. Oxford launched the Indian Drama in Translation series. In 2001, Krishnan herself moved over to Oxford, where she has continued with her dedicated mission. By next February she will have edited and published 95 books. These include recently departed Ananthamurthy’s Bharathipura.

This space was joined by other publishers that launched Indian branches: Penguin, HarperCollins, later Random House and Hachette. Their focus was books in English, but they included titles in translation. Translations were also taken on by publishers of women’s writing such as Kali for Women (now Zubaan and Women Unlimited) and Stree.

Today, nearly every publisher that brings out books in English includes some works in translation. Notable among them: Blaft Publications, from Chennai, which kicked off with Tamil pulp fiction; and Seagull, which offers the New Indian Playwrights series.

There are many reasons offered for this small explosion in translation: the emergence of Dalit and feminist movements, increased interest in India’s linguistic diversity, the growth of the English readership. Indeed, the growth of literary translation into English was a parallel development with increasing numbers writing creatively in English. I believe that both reflect something in common: the maturity of creative writing in English from India. Earlier translations had been mostly done by people who had no ear for writing in English.

The Indian English-language publishers also publish translations of titles from around the subcontinent, including Pakistan and Bangladesh. Translation initiatives are still weak elsewhere, though there are interesting new efforts, such as the Dhaka Translation Centre, which aims to partner with a small U.S. publisher.

The number of quality translators has grown, with affirmation coming from several awards. Arunava Sinha, who has been translating from Bengali, has published 28 books over the last decade and won several prizes including the Crossword and Muse awards. Since the early ’90s, Lakshmi Holmström has published more than a dozen books of prose and poetry translated from Tamil. She won two Crossword prizes and other awards. Gita Krishnankutty translates from Malayalam and also won the Crossword and Katha awards.

The number of translations being published depends, among other things, on good translations (no one can make a living yet as a literary translator), what’s available to be published, issues of rights, and assessments of what the market, still a limited one, can absorb. The three main publishers are bringing out under 50 new titles annually.

From Oxford, Mini Krishnan writes, “I work with 12 Indian languages and do anything between six to ten volumes annually. Three months ago I added a 13th language… Dogri, from the Dogra region of Jammu and Kashmir.” She is especially excited by the unrepresented languages that she brings to publication.

Reporting on their translation publishing from Indian languages, R. Sivapriya, managing editor at Penguin, writes that they published 22 titles in 2013, this year they will do 23 new titles, and they already have 22 original titles on schedule for 2015.

Minakshi Thakur, who handles translations at HarperCollins India, noted recently at DNA India, “The translation market grew marginally in terms of value in 2013, but in terms of numbers it grew considerably. Harper did 10 translations as opposed to the 5 or 6 we were doing a year until 2012; from 2014 we’ll do about 12 titles every year.” She writes, “We are focusing more on modern classics now and publishing writers who are writing in this day and age. They are wonderful books and we are publishing many languages now including Gujarati, Kashmiri, Telugu, Tamil, Punjabi apart from Bengali and Malayalam that are the usual suspects.”

The sales are modest. Arunava Sinha says that his book sales range from 30,000 to 1,500. “Most of them closer to 1,500, of course :)”

Sivapriya from Penguin writes, “The market is smaller compared to original writing in English. As a rule translations sell lesser, it is harder to get review space, to get the writers interviewed and profiled. But there are a decent number of titles that have kept selling over the years: Arthashastra, Sankar’s Chowringhee, Srilal Shukla’s Raag Darbari, Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas, Arshia Sattar’s translation of the Valmiki Ramayana, Benyamin’s Goat Days, Taslima Nasrin’s Lajja.”

She adds, “The most reviewed and celebrated novel in India in 2013 was Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s The Mirror of Beauty (Urdu). A 1000-page tome at Rs 899. The hardback sold 3100 copies and the paperback has sold over a thousand copies so far. This is to demonstrate to you the difference in numbers—an Amitav Ghosh novel would sell out a first print of 20,000 copies. Despite the rapturous and widespread praise for The Mirror of Beauty, the numbers are much less. The interesting thing is attention to the English edition took up the sales numbers of the Urdu and Hindi editions too.”

She makes a note of caution. “Translations are expensive and time-consuming and here I don’t even mean to the translator but to the publisher and the publisher’s editor. The attention and time lavished on editing and publishing and promoting translations does not pay back money in the same way English fiction/nonfiction do.”

Minakshi Thakur says, “One priority right now is to consistently try and sell 3000 copies of every translation we do. It’s a very slow market. People have strange notions about translations and don’t pick it up unless it’s a popular writer or subject.”

At Oxford, Mini Krishnan develops close relations with educators. “I find out what teachers would like to teach (most of them don’t know enough about either the history of translation or translation itself and tend to teach translation traditionally like their Eng Lit syllabus) so it is to some extent teacher-sensitization as well.”

How well do these books travel to the U.S.?

Though some books are only distributed in the subcontinent, with a bit of effort, most can be ordered from the U.S.

I use the site bookfinder.com, which searches through inventories at Amazon and small sellers or Indian booksellers selling through such vendors as Abebooks and Biblio. Readers rely on such outlets because direct distribution has many obstacles.

Only a few publishers have distribution arrangements in the U.S. Seagull and Zubaan distribute through the University of Chicago Press.

Ritu Menon of Women Unlimited explains the problem. “We have no distributors in the U.S. for the simple reason that we (like most publishers in India) are not in a position to accept returns and all U.S. distributors work on a sale or return basis. This is why we sell rights to publishers for U.S. editions of our translations.” She adds, “We have always worked with publishers with whom we have personal relationships. Both The Feminist Press and New Directions (who publish our Qurratulain Hyder titles) are old friends.”

Republishing arrangements, however, are rare. As Sivapriya from Penguin notes, “There are a few odd titles that get sold and published in Anglo-American markets. Nothing notable.”

Minakshi Thakur reports, “Even though we are actively trying to sell rights in the U.S., we haven’t met with success. There are budgetary and territorial constraints regarding e-book promotions online. It’s a sad state of affairs.”

Rakesh Khanna from Blaft notes another side of the problem: “price. Indian readers demand that Indian publishers price their books very low… which means that it’s often not worth it for an American publisher to print their own edition: the price they’d have to set to make a profit is so high that middlemen shipping the book from India can beat the price on Amazon Marketplace.”

Blaft’s experience with sales here has been disappointing. “We got a lot of blog buzz for The Blaft Anthology of Tamil Pulp Fiction which translated to some online sales, but no physical distribution—we couldn’t get any bookstores to stock our titles. We do ship books to a little Blaft USA company I set up, which distributes to Amazon and a non-profit called Small Press Distribution. We probably need to spend more energy on U.S. marketing but it’s hard to do from here and sometimes it doesn’t seem worth it.”

Many Indian books are now available as e-books. Titles from Penguin and HarperCollins are distributed through Amazon. Zubaan has an arrangement to publish e-books through Diversion Books, which are then available through Amazon and other sellers.

Unfortunately there’s no way of telling what titles are available unless you search for one you’re looking for. There is no separate marketing for e-books.

Though this would take an entire essay to cover, it’s worth noting that whether or not translations from India could find a larger U.S. readership may be affected by the choice of English. There are many translations that are fine for many readers in the subcontinent but may be difficult for an outside reader.

Daisy Rockwell, translator and writer, touched on this issue when she reviewed two translations of a single book that came out this year in India. Angarey/Angaarey was published this year by Rupa and Penguin. “Whereas in the Penguin edition, [Snehal] Shingavi has produced a polished translation that could easily be enjoyed by any reader with no knowledge of Hindi or Urdu, Vibha S. Chauhan, working with the editor of the Urdu edition, Khalid Alvi, has not. […] Not only are words that are not common in Indian English frequently found in the text with no gloss, but sometimes, entire sentences, prayers and lines of poetry are reproduced as Urdu in Roman script with little or no explanation. Chauhan’s philosophy of translation clearly demonstrates that the Rupa edition is not meant for readers that do not know Hindi-Urdu (and in the cases above, the language is not even simple Hindi-Urdu). The international reader of English will feel shut out, as will readers from South India, or Bangladesh, or elsewhere in South Asia besides northern India and Pakistan.”

So this isn’t just an issue outside the subcontinent but inside as well.

We need to find ways to raise the profile of books already in circulation. Ritu Menon says, “Raising the profile of translations is a difficult business even in India, so in the U.S. it is practically non-existent. What helps is course adoptions and reviews in specific periodicals, and of course participation in local conferences or international events, like the PEN World Writers Festival.”

And Sivapriya writes, “Reviews, excerpts, profiles, interviews in literary and mainstream publications, and being on databases—how else would anyone get to know about them?” She adds, “I am more deeply concerned about publishing and selling the books within India to their best potential. I am certain we haven’t even scratched the surface of that.”

Understandably Indian publishers will focus inside India. But something else is necessary to get the word out more widely. Perhaps the combined efforts of translators, publishers, academics, and other institutions can come together to create a central place that can showcase translations and works that should be translated. That is the hope with which I end this series.

Final post coming: responses to some comments about this series raised here and in other forums.

***

Mahmud Rahman was born in Dhaka, in what was then East Pakistan. He is the author of Killing the Water, published by Penguin India, and the translator of Mahmudul Haque’s Black Ice. He has an MFA in creative writing from Mills College. See his website here.

Read more:

Kevin Hyde reviews Mahmud Rahman’s Killing the Water

Arunava Sinha answers our Proust Questionnaire

On the Jawi Typewriter