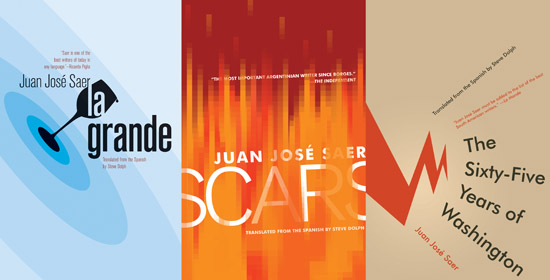

Steve Dolph is the translator of three books by the late Argentine novelist Juan José Saer, who died in Paris in 2005. All three were published by Open Letter Books, the most recent (June ’14) being Saer’s final, unfinished novel, La Grande. Mr. Dolph is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Hispanic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, where his research treats Renaissance ecopoetics and the pastoral tradition. His most recent translation, of Sergio Chejfec’s “El entenado” / “The Witness,” is available in the July 2014 issue of Asymptote.

This interview was conducted via e-mail over the early summer months, rambling like “a long afternoon’s conversation,” as Dolph commented, which is perhaps the most apposite way to approach an author so devoted to the vagaries of unfocused thought, and the ways its wandering through time and space makes itself manifest in language.

—Jeremy M. Davies

Would you mind sharing how you first became involved with Juan José Saer’s work, as reader or translator? I mean, was he an extant enthusiasm even before your association with Open Letter?

I can’t really say when as a common reader I first came to know Saer, but I was aware of his work well before the translation project came along. I know I had seen the translations from Serpent’s Tail even before I became seriously interested in translation at all. In the constellation of contemporary Latin American novelists, he figures prominently as a kind of anti-Márquez, insofar as the mythical place he most often visits in his fiction—the city of Santa Fe—is strongly affected by globalization, and fractured. In Márquez the force of history is basically recognizable, and solid, which produces a more or less reliable narrative memory and sense of place. The opposite is the case in Saer. Everything is in doubt, especially the narrative’s ability to recreate a reliable sense of place. But for me that sense of contrast only came much later, when I’d been working on the translations for a while. Before that, he was just another monster in the vast bestiary of Latin American fiction. It took a happy accident for me to get to work on his writing in translation.

In 2008 I had just come off editing Calque and was looking for a book project and shopping around some poems and stories I’d translated. Out of the blue Suzanne Jill Levine contacted me, asking if I’d be interested in translating one of Saer’s novels for Open Letter, because she was busy and couldn’t do the project. I read the book—Glosa, which was published in English as The Sixty-Five Years of Washington—sent Open Letter a sample, and because I loved the writing I asked if they were planning to do more than the one. It turned out they were planning three, and I signed up to do them all, sight unseen.

I’d like to follow up on this notion, in Saer, of all things being in doubt, and his being a sort of anti-mainstream-Boom author to boot, but first I must ask: how did Glosa become The Sixty-Five Years of Washington, in translation?

The doubt begins with the prose style. On the formal level, the narration in many of his novels, especially after Glosa, is hesitant, unsure. There’s quite a bit of direct questioning and a sort of vulnerability in the way it reaches out to the reader for support. All of which creates these long, intricate thoughts that build up, clause after clause, to form a dense cloud of uncertainty. In that syntactic fog, without a clear focus to the sentence, or the paragraph, the reader doesn’t quite know which way to turn. Within all of this, one of the central themes of Saer’s novels is the fragility of memory, how fraught our effort to reconstruct the past becomes when narration, whether through text or images, is the means we use. This sense of what memory is and how it does or doesn’t function effectively to portion out our identity is starkly different from what you find in a writer like Márquez. So as to avoid getting too wonky in the analysis, just look at the central characters in their novels and note the difference in the way they remember things: Márquez’s characters tend to have incredible memories. Not so much in Saer, or at least there’s often a strong force that undermines their efforts to remember.

Even Márquez’s own positioning as an author, from the monumental autobiography that effectively concluded his career, to the often-repeated quote that he’d gathered all of the material for his novels by the time he was eight, from his grandparents, overhead gossip, urban legends, and so on, all of which suggests that his entire oeuvre is one immense act of remembering. (Borges’s story “Funes the Memorious” is the perfect parody of this authorial position.) It’s possible that his popularity in the U.S. owes something to an analogous sense of fiction in the ’60 and ’70s, which wholeheartedly valued this strong, romantic concept of the value and reliability of individual memory. But I couldn’t say with any certainty. Lots of factors are at work when an author catches on, not least of which are their fortunes regarding their translators. (Márquez was particularly lucky with Gregory Rabassa and Edith Grossman.) Nor could I pretend to explain why some authors don’t catch on—although, to be fair, Saer has been rather lucky himself, with half a dozen books in translation and more on the way.

The decision to change the title of Glosa was made in collaboration with the publishing team at Open Letter. They felt that Gloss, the literal translation, just wasn’t cutting it—“tweeny boppy” was the term, if I recall—and we were searching around for something that captured what the book was doing. We thought that the big fat mouthful that ended up being the title captured the way things are over-explained in the book, the way that what start out as brief summaries, or glosses, of a party celebrating the sixty-fifth birthday of a guy named Washington Noriega end up taking over the story completely. But, while I think it’s perfectly true, really that’s an ex post facto explanation, to please the court, which I only put into words when people at readings started asking about the title. At the time when the book was in production, it was an intuitive decision.

Saer has indeed been lucky, considering how many Latin American authors still languish untranslated, but I suppose my ambitions for him are to wind up on as many reading lists and bookstore shelves as Rayuela / Hopscotch . . . My first Saer title was La pesquisa / The Investigation, translated by the great Helen Lane, and I was flabbergasted at the time that no one had ever so much as mentioned the book to me.

Though this does raise the question of Saer’s reputation “back home,” or in the Hispanophone world generally. How well-known would you say his work is, how “important”? Are there Saer devotees, authors identified as Saerians, Saer Studies? Or, to put it another way: how out of it are we Anglophones who are only catching up now?

Saer is widely read, and well-respected as an innovator, in Argentina at least (I can’t speak to his reputation elsewhere in Latin America, but this is really another question altogether, one that has more to do with the marketplace than with “taste” per se), although when I tell people who know about this kind of thing that I translate Juan José Saer they look at me sort of quizzically, like Why him? Or immediately they wonder how I came to know of Saer’s work. It’s difficult to compare reputations between literary traditions, but these reactions make me think that in Latin American letters Saer is considered a sort of weird cousin to, say, Ricardo Piglia, another Argentine with a taste for police drama, and with a much broader fan base. But then again, those same people are surprised when it comes out that I’m familiar with the work of Walsh, Lamborghini, Felisberto, Chejfec, and other weirdos from the area.

There are indeed Saer devotees, and a great body of critical literature on Saer, which includes shocking internecine polemics regarding his legacy (nowhere, by the way, except in the British press, is he considered “the most important Argentinian writer since Borges”). One book, Zona de prólogos, edited by Paulo Ricci, would be a really great resource for fans of Saer in English. As the title suggests, it’s a collection of prologues to Saer’s novels, all written after the fact, by authors and critics. Unfortunately this book will never be translated. The last part of that question, regarding our backwardness in the U.S., is really much too complex for me to treat here with anything resembling delicacy. From what I’ve read of reviews, I would say that critics in the U.S. generally get what Saer is up to, and do right treating the work as literature and not as an exotic stuffed bird. At the same time, Saer’s writing tends to be relatively “local” in the sense that he’s writing about places, and ways of interacting with those places, that are generally unfamiliar to people outside of the Paraná River delta.

The police investigation in La pesquisa is really only half the story, and maybe the least compelling half. If we’re out of it in the U.S., it’s relative to the state-sponsored violence that permeates the history of the twentieth century in Latin America, and which generally arrives here in caricatures—El Che, Fidel, the FARC, Shining Path, the Falklands, the Knights Templar, etc.—and even less the literature that comes out of that violence. The great exception to that rule is of course the Roberto Bolaño phenomenon. Although, again, the critical reaction to his novels has been partial—much too partial—to his connection with the Beats. Saer is of course another writer concerned with the effects of violence on people. Saer’s novels often work toward a representation of the swarm of experience, and within that swarm there’s no possible transcendent meaning, only events, presence, intensities, entropy, decay, and yet, language is a thing, it exists. And people use language to assign value, so that when things happen, they “mean something.” Human experience might be characterized, in Saer’s work, as the stubborn insistence on meaning in the face of chaos. But this isn’t new; it’s what the novel has done since Cervantes. Alongside that general function of the novel, there is definitely a permanent interest in Argentine writing to respond to state violence in a way that isn’t a caricature. So much interest in the detective genre comes from somewhere, and in Argentina it’s from a very particular relationship to the figure of the police.

Stay tuned for Part II of Jeremy M. Davies’s conversation with translator Steve Dolph!

***

Jeremy M. Davies is Senior Editor at Dalkey Archive Press. His first novel, Rose Alley, was published in 2009; his second, Fancy, will be published by Ellipsis Press in November 2014.