Read all previous posts in Asymptote’s “Mimes” translation project here.

Mime VIII. The Nuptial Eve

This new-wicked lamp burns a fine, pellucid oil before the evening star. The threshold is scattered with roses that the children have not gathered up. Dancers balance the last torches that wave fiery fingers into the shadows. The little flutist has blown three more harsh notes into his flute of bone. Porters have come bearing cases brimming with translucent anklets. This one has coated his face in soot and has sung me a song that mocks his deme. Two women, veiled in red, smile in the settled air, rubbing their hands with cinnabar.

The evening star rises and the heavy flowers close. Near the wine vat covered by sculpted stone, a laughing child sits, his radiant feet strapped into sandals of gold. He waves a pine torch and its vermillion braids whip out into the night. His lips hang open like the halves of a gaping fruit. He sneezes to the left and the metal sounds at his feet. One bound and I know he will be gone.

Io! Here comes the virgin’s yellow veil! Her ladies hold her up beneath her arms. Do away with the torches! The wedding bed awaits, and I will guide her into the plush glimmer of the purple cloth. Io! Plunge the wick into the sweet-scented oil. It sputters and dies. Put out the torches! Oh my bride, I lift you to my chest, that your feet do not crush the threshold roses.

*

Phillip Griffith: Stunning images mark Mime VIII. In translating, I spent some time with the opening image of the refined lamp oil, ultimately amping up the power of the French adjectives “fine et claire” with the less common English “pellucid.” When focus returns to the perfumed oil at the passage’s close, the highly visual, almost tactile, “pellucid” is enhanced by the further description of the oil as “sweet-scented” or “odorante.” Then, too, the translucency of “pellucid” plays off the translucent anklets presented by the porters. Captivating as well was the pine torch waved by the Cupid figure. Though the French “s’eparpillent” implies a scattering and fading of the fire, I could not resist the play on Schwob’s description of the torch as “cheveux vermeil,” rendering them as braids whipped about by the boy. (Additionally, this hopefully captures some of the gold-shod Cupid’s mirthful energy.) And finally, to my English ear (and by felicities of direct translation more so than by my own efforts), “the threshold roses” is an equally, if not more sonorous, rendering of the already quite beautiful closing image offered by Schwob’s “les roses du seuil.”

*

Mime IX. The Beguiled

I beg whoever would read these lines to join in the search for my cruel slave. He fled from my bedroom at two in the morning.

I had bought him in a Bithynian city, and he smelled of the balsam of his land. His hair was long, his lips soft and sweet. We climbed into the husk of a boat narrow as a bean’s shell, and the bearded sailors, fearing tempests, forbade us to cut our hair. And by the glow of the new moon, they threw a spotted cat into the sea. The wooden oars and linen sails that power such barks took us through the Pontic sea’s black waters to the shores of Thrace, where the foamy beach turns purple and saffron at sunrise. And we crossed, too, through the Cyclades, landing on the isle of Rhodes. Not far from there, we disembarked our slender hull at another small island whose name I will never reveal: for its grottos are covered in red grass and seeded with green bushes, its meadows soft as milk, and all the berries on those bushes—whether murky red, clear as grains of crystal, or black as a swallow’s head—have a delicious juice whose savor revives the soul. But like an initiate into its mysteries, I will say no more of this island. It is a blessed place where one finds no shadows. I made love there for one whole summer. In autumn, a flat barge brought us to this country, for my accounts had been neglected and I wanted to raise enough silver to dress my slave in fine linen tunics of byssus. To think that I have given him golden bracelets, and staffs wound in braids of amber, and gems that gleam in the dark.

How miserable I am! He slipped from my bed and now where will I find him. Oh, women who cry out to Adonis each year, do not hold my plea in contempt. If this criminal falls into your hands, weave iron chains about him; tie tight his legs in shackles; throw him into a stony dungeon; drive him to the gibbet, and may the Scourge of the Flesh bend his head with his devices; sow handfuls of seed around the torturer’s hill so vultures and crows will fly faster to his flesh. Or, rather (because I have no faith in you who would pity a skin so pumiced and polished), don’t touch him, even with the delicate extremities of your fingers. Turn him over to your young messengers that they would deliver him to me in turn. I will know how to punish him myself: I will punish him cruelly. By the Gods incensed, I love him, I love him.

*

Phillip Griffith: I have taken my greatest liberty in the English rendering of Mime IX’s subtitle. I opted against the more direct, latinate option “the enamored” for “l’amoureuse” in favor of “the beguiled.” With its prefix’s provenance in English’s Germanic roots and the stem’s origins in Provençal (with possible borrowing from Germanic origins, here, too), “beguile” or “The Beguiled” conveys the sense of a mistress, or a master, under the spell or wily charms of a slave. (The absence of gender in English nouns playfully masks in translation what is grammatically denoted as a feminine speaker in the original French text.) As for the image of the ship that delivers the speaker and the slave to their blessed isle, the play of “coque” in the original French—which can refer to a ship’s hull, a variety of shells (egg, bean, even those of some mollusks), or a cocoon or husk—allowed me to triangulate the French through several otherwise unrelated images in English: “the husk of a boat narrow as a bean’s shell” and “slender hull.”

In both Mimes VIII and IX, I faced the question of how to render the fantasized Ancient Greek setting of these prose poems. Thus, in Mime VIII, the political division of the “deme” and the exclamation “Io!” remain unchanged, as does the “Pontic sea” in Mime IX (“la mer Pontique,” an older name for the Black Sea). However, to render Mime IX slightly more accessible, I elaborated on the tunics of byssus (a rare, silky, fine linen cloth made from flax) and changed “electron” to its modern name “amber,” where an elegant elaboration seemed impossible in the space of the sentence enumerating the gifts bestowed upon the slave by his enamored mistress.

***

Mime VIII. The Wedding Eve

The new wick of this lamp burns on oil, slender and clear against the evening star. The threshold is scattered with roses that the children did not carry away. The dancers swing the last torches, whose fingers of fire stretch out towards the shadows. The little flautist has again sounded three shrill notes on his flute of bone. The porters have come, bearing coffers filled with translucent ankle rings. This one dusted his face in soot and sang to me the jests of his deme. Two women, veiled in red, smile amid the softened air, anointing their hands with cinnabar.

The evening star rises and the heavy blossoms close. Near the great wine vat, covered by a sculpted stone, a laughing child, whose luminous feet are shod in golden sandals, sits. He swings a pine torch and his vermillion hair rays out into the night. His lips are parted, like a ripening fruit. He sneezes, turning left, and the metal resounds at his feet. I know that he will soon take his leave.

Here it comes, the yellow veil of the virgin bride! Her maids support her on their arms. Send away the torches! The nuptial bed awaits her, and I shall guide her towards the purple fabrics’ soft shimmer. Immerse the lamp wick in fragrant oil, for it flickers and dies! Put out the torches! Oh, my bride, I raise you to me, so that your feet do not brush the threshold’s roses.

*

Susie Cronin: For the torches’ “doigts de feu,” in Mime VIII, I was tempted to overembellish the corporeal qualities bestowed upon the torch flames with something to the effect of “the last torches whose tongues of flame lap the darkness.” I chose instead to render it more faithfully to the original, with “whose fingers of fire stretch out towards the shadows.”

My quick search into Ancient Greek terms taught me that a “deme” was a subdivision of land, a community from which the soot-tarnished figure sings gossip and what I imagined to be lyrics satirising in turn various members of that community.

From the final paragraph of Mime VIII, I purposely omitted the two occurrences of “Lo!,” present both in the French and in the 1901 English translation by Lenalie, thinking it too antiquated for a fresh translation. The alertness and urgency of “Lo!” are in any case preserved in the series of exclamation marks which punctuate the closing lines of Mime VIII.

I opted, rather than literally translating “je te soulève contre ma poitrine” with chest or breast, for a simpler and no less theatrical “Oh, my bride, I raise you to me…,” thereby simplifying dated formulations of breast or bosom.

***

Phillip Griffith is a poet and Ph.D. candidate in French at the Graduate Center, CUNY. He teaches French language and literature at the City College of New York and at Baruch College. He holds a BA from the University of Georgia and an MA from Columbia University. His poems and translations have appeared previously in La Petite Zine, Esque, N/A, and Philosophical Forum.

.

Susie Cronin studied Modern and Medieval Languages at King’s College, Cambridge, and the Sorbonne IV, Paris. She has a particular interest in Italo Calvino’s interactions with the OuLiPo in ‘60s Paris. She translates from French and Italian and currently lives in Dublin.

***

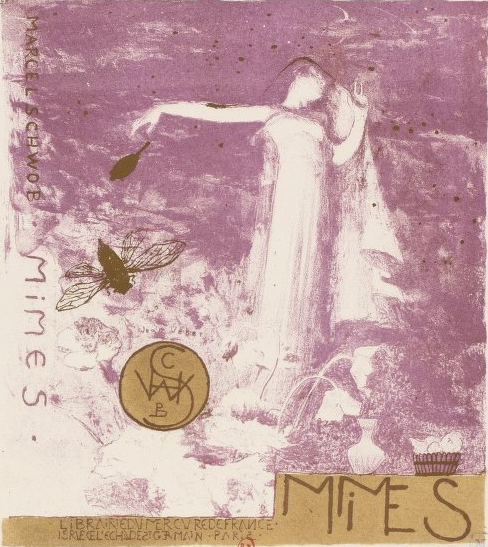

Image: Jean Veber cover illustration via Bibliothèque nationale de France