“Umm. I’ve studied in English… but my mother tongue is Hindi, of course,” I said confidently to my Nigerian housemate, who had asked about my “first language” while I was struggling with my newly acquired culinary skills during breakfast.

In a heterogeneous environment, students collect crumbs of the languages around them, believing they are true connoisseurs of culture. I should have anticipated her next question: “So how do you say ‘Good Morning’ in your language?”

Shubh Prabhat. I had stored it somewhere in my preconscious memory. It’s one of those things that you know you know, but you can’t remember at the urgent moment. That’s forgivable when it’s an uncommon word. But this was “good morning”—probably one of the first phrases one learns while learning a new language. And this wasn’t a new language: it was supposed to be my “mother tongue.”

How could I have known? Firstly, we don’t wish each other “good morning” anymore (save for the elongated “good moooorning, ma’am” that we used to cry out in school). Yet I instinctively know the word for it in English. Secondly, how reasonable is it to expect a product of the Delhi Hinglish culture to know this, when the only time we hear a greeting in Hindi is Amitabh Bachchan concluding an episode of Kaun Banega Crorepati (Indian version of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?) on Sony TV with “Good night, Shubh Ratri, Shabba Khair, Khuda Hafiz…”?

Consider the challenge posed by the following passage.

Can you spend the next twenty-four hours of your life using just one of the two languages you think you know, either language A or language B, without using a single word of the other language? I have found that anyone who survives the test for twenty-four hours comes out having lost about 10 kilos of linguistic flab within that short period and a corresponding quantity of mental slackness accumulated over the years through the use of saturated Hinglish. Mentally, this person emerges with a leaner, fitter mind and finer-tuned thinking machinery, and discovers that s/he has linguistic muscles s/he never knew existed. (Trivedi 2011:xxvi)

We can effortlessly say “koi problem nahi,” “please kar de yaar,” “bhaiyya, yahan se left lelo” (and I can assure you that half the people I know would need to consult a dictionary if one had used “baayein” instead of “left.” I admittedly had to pause while writing this to confirm that “baayein” does, indeed, mean left), but if you ask us to speak in Hindi for one whole day, without using even one English word, we would tell you how absurd a suggestion that is and politely refuse.

I don’t mean to rant about my dilemmas as a shudhh Hinglish speaker. I am writing this to confess my (extremely frustrating) insufficiency to take the above test for language B—Hindi, in my case. I may have tried my hand at translating a handful of English poems into Hindi. And I’ve prided myself on it for the past few years. But it just struck me how self-indulgent I have been.

I have grown up believing that it is somehow “cooler” to speak English. I have grown up hearing people making fun of “HMTs” (Hindi-Medium Types); internalising the humiliation that comes with knowing and speaking your own language. Hindi movies are cool, but who ever “would touch a Hindi newspaper, dude”? I would have celebrated this defeat of Hindi in the battle of linguistic social superiority had I not been raised in a family that appreciates both languages.

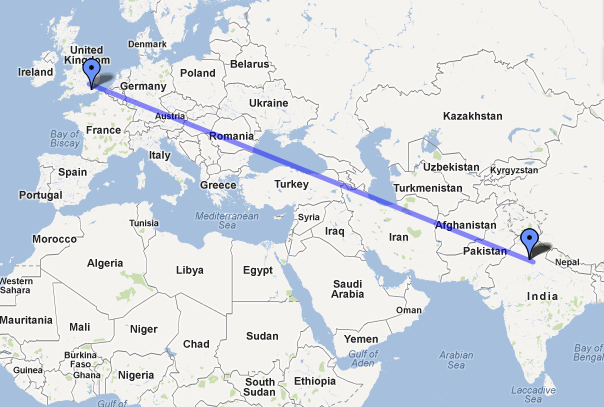

Ironically, it has taken an enrolment at the University of London for me to understand how misplaced our sense of embarrassment is. What I am now mortified of isn’t the fear of mispronouncing an English word—it’s coming to terms with the fact that I call myself a literature student from India without ever having read a novel in my own language.

Maybe it is time to lose that linguistic flab—formed layer upon layer by residual colonial insecurities—settled so imposingly over my fragmented, metropolitan mind.

Reference

Trivedi, Harish. 2011. “Foreword” to Rita Kothari and Rupert Snell (eds) Chutnefying English: The Phenomenon of Hinglish. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. vii-xxvi.

***

Mohini Gupta is currently pursuing an M.A. in cultural studies at SOAS, University of London. After graduating in English literature from Lady Shri Ram College, University of Delhi, in 2012, she was granted a scholarship at the Young India Fellowship Programme (a yearlong liberal arts programme in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania). Passionate about poetry, translation, and music, she is keenly interested in an academic exploration of the politics of language in India. Follow her at @mohini_28_gupta.