As the diplomatic stand-off between the United States and Cuba reaches its fifty-fifth year, an anxious audience packed into 61 Local in Brooklyn, New York to hear from Cuban writer Leonard Padura and his translator, Anna Kushner.

Online translation journal Words Without Borders gathered Padura, Kushner, and writer-editor Jonathan Blitzer to discuss the recently released Padura novel The Man Who Loved Dogs (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux 2013), translated by Kushner. The evening included a reading by Padura in the original Spanish, followed by Kushner reading the same passage in English.

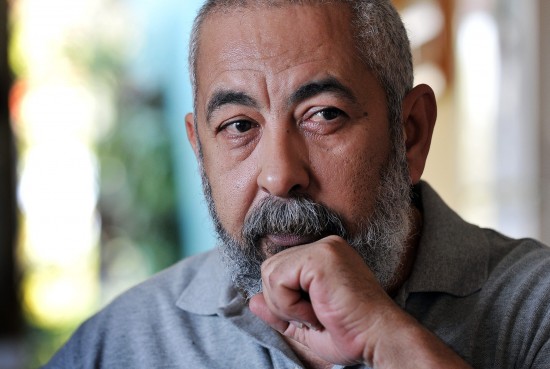

Padura’s output includes short stories, journalism, novels, and criticism. He was born in 1955 in the working-class Havana suburb of Mantilla, where he still lives. He is best known for his detective novels centered on Inspector Mario Conde—like Padura, a man whose childhood takes place almost entirely in post-Revolution Cuba.

He has, as John Lee Anderson’s New Yorker article attests, forged a position as a celebrated member of the Cuban establishment of which he is also a critic. In 2012, Padura became the first Cuban author to be the honoree of the Semana de Autor at Havana’s Casa de las Américas.

The Man Who Loved Dogs, translated by Kushner, focuses on the 1940 murder of Leon Trotsky in Mexico at the hands of Stalinist agent Ramón Mercader. Upon release from prison in 1960, Mercader spent the rest of his life in Cuba.

Speaking with Blitzer and audience members, Padura addressed the predicament of Cuban writers among international audiences. Many Cuban writers, Padura said, are anonymous outside their country because the themes they address are hyperlocal, approaching journalism as much as fiction.

“I think that many Cuban writers, when they confuse the two genres, are making literature that is way too specific, way too local and dependent on their specificity,” Padura said. “And as such, that literature just isn’t very visible outside of Cuba because it’s the kind of literature that only appeals to other Cubans.”

Padura defended a literature that relies on less explicit techniques to illuminate the present.

“There are novels, for example, about the Roman Empire that teach us more about modern man than modern novels do,” he said.

Ironically, the very same quasi-journalistic fiction keeping contemporary Cuban writers from widespread international recognition still doesn’t prevent a flurry of questions for Padura in his travels abroad. The Cuban novelist admitted that he and his peers face a similar dilemma: when international audiences’ discovery of their work almost encourages a politicization of their work.

“There’s something I always like to say because people misunderstand my positions: I say here in New York, in Brooklyn, exactly what I say in Havana—I don’t use two different types of language,” he said.

Padura’s comments speak to the need for increased cultural contact between readers in the United States and Cuba (achieved through translation, of course!). The cruel imbalance between the sheer quantity of works by American writers translated abroad and those translated into English for an American readership becomes more deleterious considering the limited information Americans receive about countries with which the United States does not maintain diplomatic relations.

Padura acknowledged that his critical views may have caused discomfort, particularly when he addressed the position of the Cuban writers as honoree at the 2012 Author’s Week at Casa de las Américas. Such criticism, Padura told the audience, is necessary to combat what he considers as a complacent intellectualism in Cuba.

“This has, of course, a very disagreeable consequence for me, but it’s a role that I’ve assumed with great responsibility, and that consequence is that I can’t be like Paul Auster,” Padura quipped, referring to the contemporary American author most closely associated with Brooklyn.

“When people interview Paul Auster, they ask him about literature, film and baseball, which are the things I’d like to talk about. What they ask me about is what’s going to happen in Cuba after Fidel Castro dies, what’s going to happen with the Cuban economy, and always ask me the same thing: I don’t have any reason to know these things. For this reason, I’d like to say here in Brooklyn, that there’s many days I wake up and I would like to be Paul Auster.”

***

Eric M. B. Becker is a writer, translator, and award-winning journalist from St. Paul, Minnesota. His translation interests include contemporary writers from Brazil and Lusophone Africa, and the Brazilian modernists. His translations of Brazilian writer Edival Lourenço most recently appeared in Frankfurt Book Fair commemorative edition of Machado de Assis Magazine, a publication of the National Library of Brazil and his translations of Mozambican writer Mia Couto have appeared or are forthcoming in Asymptote and The Massachusetts Review. He lives in New York.

***

Image via prodavinci.com.