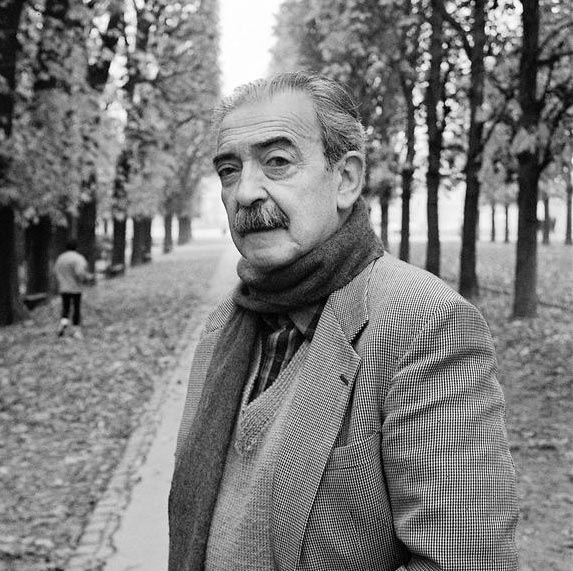

Three days of national mourning were declared in Argentina to commemorate the life of poet Juan Gelman, who passed away at eighty-three on Tuesday, January 14th in Mexico City. Silvina Friera of Pagina/12 remembered the Argentine poet’s great contribution to Spanish literature, stating “we have lost a man who transformed wounds into memorable verses…an untamable voice, so close and so beloved, whose deep cadence crackled with an elegant and playful irony.”

Born in Argentina in 1930 to Jewish Ukrainian immigrants, Gelman began developing an ear for poetry at age five as he listened to his older brother recite Pushkin in Russian. Although he was not able to understand the meaning, he was fascinated by the sound and rhythm of the words.

Gelman cites his first muse as a beautiful, dirty-kneed girl from his neighborhood. He tried to impress her with lines by Almafuerte, passing them off as his own. When this failed to get her attention he decided to create his own rhyming verses. Gelman continued with poetry, first publishing work at age eleven in the magazine Red and Black.

Active in the Argentine Communist Party from the age of fifteen, Gelman and other young poets from the Party established the writer’s group Pan duro, dedicated to publishing their works. To raise money for the books that they would vote to publish they pre-sold copies and held parties and concerts. Gelman’s Violín was chosen as the group’s first publication in 1956.

In the 1960s Gelman’s politics became more radical; while many in Argentina believed that Socialism could be achieved through peaceful means, others—Gelman included–looked to Cuba and saw another model. In 1967 he joined the Peronist Revolutionary Armed Forces, a group which sought to overthrow the military dictatorship that had taken control of Argentina and later joined with the Montoneros. In 1975 he was sent abroad to publicly denounce the violence and repression of the Triple A, a right-wing death squad backed by the Argentine government. Soon after, his daughter, son, and his pregnant daughter-in-law were all kidnapped. His daughter was later released, but his son and daughter-in-law joined the 30,000 citizens who were “disappeared” under the military regime. Gelman dedicated himself to searching for them, and he was eventually able to uncover evidence of his son’s torture and murder. He also found details on the birth of his grandchild, born during her mother’s incarceration and then given up for adoption. Gelman would spend years searching for his lost granddaughter, until he was finally reunited with her in 2000.

Gelman’s work is often called political, but such labels are inadequate to describe his innovative use of language and playful stylistic subversion. Writer John Berger likens Gelman’s poetry to the work of Frida Kahlo, as both artists drew inspiration from their deep pain–Khalo’s physical, Gelman’s emotional, stemming from his great personal loss. Gelman worked ceaselessly to vindicate the murder and kidnappings of his family and others. He did not celebrate in 2011 when his son’s murderer was sentenced to life in prison, stating that he felt “neither happiness nor hate, nothing.” Instead he continued to explore his emotions through his writing, releasing his last book, Hoy, in 2012, after the sentencing hearings of the torturers of Automotores Orletti, a detention center during the Argentine dictatorship.

Juan Gelman published over thirty books of poetry and has been awarded numerous prizes, including the Argentine National Poetry Prize in 1997, the Pablo Neruda Prize in 2005, and the Cervantes Award in 2007. “Neither the account of his deserved awards, the review of his imposing body of work, nor the memory of his battles and his losses can express the magnitude of what has happened: with Gelman goes the poet, journalist, and activist who broke down the limits of language to create new life.” As Silvina Friera asserts, no words can do him justice, except maybe his own words. Below, an excerpt from Juan Gelman’s Oxen Rage (Cólera buey, 1965) translated by Lisa Rose Bradford.

See more work by Juan Gelman and translated by Lisa Rose Bradford in our Spring 2013 issue. Read Bradford’s moving reflections on his life and death at Words Without Borders.

Heroes

the suns are sunning and the seas still seaing

the druggists are specific

dictating delicate prescriptions for shock

breaking fast in their great beakers

my thing is to gelman

we have lost our fear of the great stallion

successive hatchets are upon us

and it always dawns upon our testicles

it’s no small thing that this should happen to us

in light of the love misdealt these days

the decks of catastrophes the debts

beloved be those who loathe

progeny that peck about at my livers

and their disgrace and grace is to not be blind

great mother marie

great father steed

giddy up gelman on i say

go gelmaning on to meet the most beautiful ones

those who launched victories in their great defeat