For the ongoing work Words, Recollected, the artist tries to remember words in Armenian and writes them phonetically on the wall. Each presentation of the work is different as the artist recalls anew a language he was never taught. The video Learning Piece: Be Patient, My Soul documents the artist trying to learn old revolutionary lyrics from an elderly Armenian. In the video MG, the artist stands before a mirror and practices saying his name in Dutch and French.

Currently Garabedian is one of sixteen artists participating in Armenity: Contemporary Artists from the Armenian Diaspora, the pavilion of the Republic of Armenia at the Venice Biennale. Commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, the exhibition takes place on the island of San Lazzaro, home of the monastic order founded in the eighteenth century by the Armenian monk Mekhitar. The monastery became an important center for the study of Armenian language and culture. It was here that Lord Byron came in December 1816 and, finding that his mind "wanted something craggy to break upon," began his study of Armenian. Garabedian's contribution to Armenity includes the work Untitled (Daniel Varoujan, Ghent), 2011. Varoujan, an important Armenian poet, studied at Ghent University for three years before being killed during the genocide of 1915. Garabedian's intaglio prints of Varoujan's verses are stacked in "endless copies" for viewers to take away as they wish. With raised white letters on white paper, each verse in Armenian is incomprehensible for most viewers and barely visible as image, Varoujan's verse on the verge of disappearing even as it circulates. In another work, Garabedian quotes lines from Gurgen Marahari's novel The Burning Orchards, set in Van, in Eastern Anatolia, in the years leading up to its siege by Turkish forces in 1915. The lines, occurring in a passage that celebrates both the beauty of the ancient city as well as the endurance of its residents' memories, are recast by the artist as a neon sign: "The world is alive. And Van is alive."

In the following interview, Garabedian addresses the complexities of diasporic subjectivity, the experience of translation and untranslatability, and artistic strategies of quotation and repetition.

—Eva Heisler

Because diaspora and language are central preoccupations of your work, I'd like to begin by having you talk about your family background, and how this informs your artistic practice.

I was born in 1977, in Aleppo, Syria, where my father was born and raised. My mother was born in Beirut, Lebanon. My parents are Armenian by descent, and were both raised in Armenian communities in diaspora. Their parents and grandparents lived within the then large Armenian communities in Anatolia, which is now Turkey, respectively in the areas around Van and Moush, and in 1915-1916 had to escape the Turkish atrocities and massacres during the Catastrophe. The generation of my grandparents grew up in orphanages, in their case in Syria and Lebanon.

My father used to work in Aleppo and Beirut and his job frequently took him to Europe. My parents wanted to live in Beirut, but because of the civil war in Lebanon (which officially lasted from 1975 until 1990), among other things, my parents decided to relocate to somewhere central in Europe, and by accident that turned out to be Belgium. My parents carry with them the Middle Eastern culture, history, and the Arabic language with which they grew up. One could say that I am a migrant of the first generation here in Belgium but, historically speaking, I'm a migrant of the second, or third, generation. This personal sketch already shows some of the complexities of diaspora that resist being fitted and fixed.

I not only share an Armenian ethnic origin, but also a diversity of (trans)cultural capitals or Presences collected from the different countries of migration; Anatolian, Syrian, Lebanese, Middle Eastern Presences in combination with a Belgian present/Presence. Because of the contemporary political, economic, and cultural situation of Lebanon and Syria, and of the Middle East in general, these places (and their histories) are meaningful, significant, and vital presences in my daily life. Diaspora means experiencing a disseminated, shattered, divided self.

In diaspora, both the old and the new, the original family and the new community, their languages and cultures, appear equally attractive and problematic, resulting in a subjective condition marked by longing and belonging, and by always being in between cultures, times, places—layering, contaminating, and balancing different pasts, presents, and futures—being here, and, at the same time, always already there. It means to keep feeling threatened by this past, by this former territory, and to be caught up in memory, the memory of a happiness or a disaster—both always excessive.

Diaspora is also marked by translation. Inhabiting two or more languages concurrently challenges our subjectivity, as we are pending, undecided, between two languages. Bilingual or multilingual consciousness is not the sum of two languages, but a different state of mind altogether—defined by the mode of translation. As a foreigner, you are constantly translating, in both directions. You find yourself in a position in which you can no longer speak of a mother tongue—always in between (two, or more) languages, always speaking the words of others.

Being essentially a translator, the foreigner is intimately aware of the untranslatability, and of the foreignness (or otherness), of language; the uncanny, intractable, and disturbing character of language—experiencing that we not only speak a language, but are also spoken by it.

Your works can be both personal and critical, expressive and theoretical. You have written elsewhere that your way of working involves moving back and forth between your own experience, or the recounted experiences of your family, and theoretical texts. Can you talk some about this process, and how the mix of discourses, borrowings, and visual forms contribute to your exploration of diasporic subjectivity?

In my research, I contemplate the conceptual possibilities of the work of art. I often use modes of repetition that reference literature, philosophy, cinema, pop culture, and the works of other visual artists—citing, replicating, and distorting references, exemplary modes, and works from art history and from my own history. I employ references as structures or elements upon which I can build, adding different layers, or contaminating them with altogether different contexts.

My interest in citation developed instinctively, probably through the experience of growing up with two languages, which engendered the feeling of always speaking with the words of others, perhaps also by encountering the early films, full of citations, of Jean-Luc Godard, at a young age, and through growing up in the nineties with the art of sampling as practiced in hip hop culture.

My use of citations or references also comes from my interest in the idea that identity is always a borrowed identity. One can never pretend to be someone out of the chain of the past. One is always speaking with the words of others. Talking with the words of others requires a library (and a dictionary) of the words of others. In my work, I use talking with the words of others and the construction of a (personal) library as a conceptual artistic strategy. My use of modes of repetition also relates to the Catastrophe; after a disaster, only thinking in ruins, in fragments, cut-outs or debris, remains possible.

Your video installation without even leaving, we are already no longer there (2010-2011) consists of videos taken on a trip to Beirut with your mother in an effort to record her recollections of growing up in an Armenian neighbourhood. Could you talk about the process of making this work?

I was invited by the Werktank, a Belgian platform for installation and media art, to propose a project. For without even leaving, we are already no longer there, I travelled with my mother and grandmother to Bourdj Hamoud, the Armenian quarter of Beirut. Both my mother and grandmother were born and raised there, but they hadn't returned for over twenty years because all their family had moved from Beirut to Los Angeles.

The installation constitutes a portrait of my mother: of her personality, her memories, her history, and her past; and a portrait of the area around Arax Street in Bourdj Hamoud, where my mother lived until the start of the civil war. Beirut is the city of her youth, of my first years, the city of broken promises, of ghosts and ruins, of what could have been. And among those ruins: a neighbourhood, houses, people, and visitors. This city is like a siren call, a ghost town that keeps haunting.

The installation has been presented in different forms. In one form, five videos, with lengths varying from fifteen minutes to fifty minutes, are shown on monitors that are presented in a single space, and in which the viewer can only see one monitor at a time. In another form, three synchronous thirty-minute video projections are presented next to each other. The three projections could be viewed individually and/or simultaneously. The videos consist of long takes in which we see the Armenian quarter, and my mother visiting once familiar places, literally getting lost in the streets of her youth, with hardly any dialogue and no off-screen comment. Over the images, my mother's recollections appear sporadically as text.

Can you speak about the role of memory, both personal memory and historical memory, in your work?

I touch upon different kinds of memory in my work. One is "postmemory." Diasporic subjectivity is marked by "postmemory"; to grow up dominated by narratives that precede your birth. Even though the Catastrophe did not take place in my lifetime, nor in that of my parents, the narratives and experience of that history had a major influence on us (with differences for each generation). These experiences were transmitted so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right. To grow up with inherited memories means to be shaped, however indirectly, by fragments of events that still defy narrative reconstruction and exceed comprehension. These events happened in the past, but their effects continue into the present.

I'd love to hear more about Tass, July – August, 2007, the work that involved your mother reading your future in your coffee grounds for forty days, and then recording her readings.

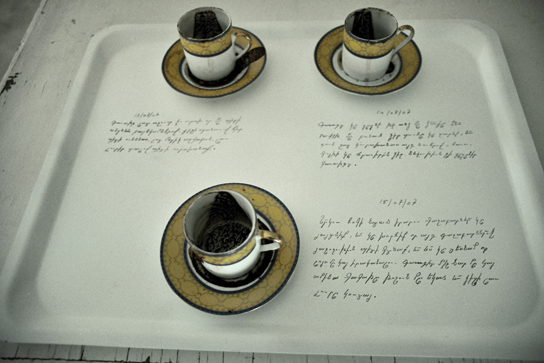

My mother often reads her future in grounds of coffee, unfiltered Middle Eastern coffee. This is a tradition in many different Middle Eastern countries. It is a way for women to spend time together, and the predictions are based on certain images that appear in the coffee grounds. For example, a bird means that some kind of news will be forthcoming. This tradition is of course a bit tongue-in-cheek, and the predictions are normally not taken very seriously. A few of my works focus on certain traditions, like the preparing of traditional dishes which are often very time-consuming, and which can vanish or get lost between generations. The installation is a tongue-in-cheek self-portrait, touching on themes such as chance, language, and diaspora.

About every other day during the summer of 2007, I had my fortune read by my mother. The texts of the forty predictions were written in Armenian on seventeen white trays of different sizes and read onto tape by my mother. The actual cups with the coffee sediments were fixed and varnished, preserving the coincidental and temporary "image" which appears, and in which one reads the future. The installation consists of the different trays presented on tables, in a space where one hears the predictions in Armenian.

Related to the above works, could you talk about the role of storytelling in your work?

I'm interested in the dynamics between comprehension and incomprehension. I like listening to a foreign language that I completely don't understand. I like the space of getting lost and of "not-knowing," of deciphering. Often I position the viewer or spectator in a position of not-understanding, or within this dynamic of understanding/not-understanding. I'm not a traditional storyteller, I suppose. Every story has a beginning, middle, and end, but I don't necessarily present these parts in chronological order.

Roland Barthes writes, "We often hear it said that it is the task of art to express the inexpressible; it is the contrary which must be said (with no intention of paradox): the whole task of art is to unexpress the expressible." A work of art has the power to displace, confuse, unravel, and lessen knowledge, to unlearn the learned and to unexpress the expressible. Art can operate outside the linear or binary axes of ignorance/knowledge and comprehension/incomprehension.

"Philosophy helps us understand the world better, while art helps us understand it less," states curator and writer Anthony Huberman. And the philosopher Jalal Toufic advances that "art and literature do not provide us with the illusion of comprehending, of grasping, but allow us to keenly not understand"; art provides us with "incomprehension in an intelligent and subtle manner."

Many of your works can carry multiple, even competing, readings. For example, Search and Destroy (And Honey, I'm the world's forgotten boy) (2012) is a public work that consists of the military phrase spelled out with the empty aluminum casings of former neon-sign letters. The empty letter-forms are propped along the façade of a historical building in Ghent. It's a disturbing phrase, a legacy of the Vietnam War, but it is also the name of a song recorded in 1973 by the protopunk rock band The Stooges. Accompanying this work is a text in which you translate Iggy Pop's lyrics (with their refrain "And I'm the world's forgotten boy / The one who's searchin', searchin' to destroy") into Armenian.

I have two questions about this work. The first has to do with your choice to focus on this particular phrase. Does "search and destroy" serve as a trope for your own practice as an artist, or your own relationship to history?

Secondly, can you speak to the role of translation in your work? What, for example, is the significance of translating Iggy Pop's lyrics into Armenian on the occasion of a public work installed in the historic center of Ghent?

In 2012, I was invited by SMAK (Ghent, Belgium) to participate in TRACK, an exhibition that took place mainly in public spaces in Ghent. The Arab Spring moment in Syria was being hijacked and instrumentalized by different powers. The violence, the destruction of Syria and of sites of cultural heritage, were intensifying. "Search and Destroy" was the name of a military tactic used by the Americans during the Vietnam War.

On the other hand, the historical center of Ghent is full of old buildings, which are mainly attractive for tourists. For the exhibition, I had the words "SEARCH AND DESTROY" leaning against the oldest building in Ghent, het Groot Vleeshuis, a place where once the meat merchants would sell their products. In relation to history, and the presence of the historical in the present, there is a tension between too little and too much. The modernist notion of a radical break with the past is unrealistic and too much of the past in the present can be very dangerous.

Furthermore, the song by the Stooges contains the lyrics (which I use in the title of the piece): "And Honey, I'm the world's forgotten boy." This, of course, resonates with the "forgotten," unknown status of Armenian history in the world today. It is a song I used to cover when I was younger and used to perform with a post-punk band. The translation of the lyrics already existed since 2006, as an autonomous piece. It was reproduced in the book Happy when it rains (2006) and I included a different version in the catalogue of TRACK. It is a kind of self-portrait, I guess.

"Search and Destroy" in another sense also resonates with the concept of "creative destruction," which Nietzsche used in reference to Dionysus, whom he called "creatively destructive" and "destructively creative." The Apollonian does not exist without the Dionysian. The balanced, rational, reasonable is not without the visceral, dark, hard-to-understand part, which emerges from inner layers of the self. It is in this Nietzschean sense that "Search and Destroy" is used and appears in skate-culture.

You have described language as "at the same time a homecoming and foreign or even enemy territory." This statement is certainly interesting in the context of Search and Destroy (And Honey, I'm the world's forgotten boy). Can you say more about this?

Apart from Armenian and Dutch, my parents also used a third language, Arabic, the language of their education and public life, which they employed as a secret code toward us, their children, when they wanted to discuss something in private. Language has the power to create an immediate sense of inclusion or exclusion. If you want to stigmatise someone as a foreigner, simply speak a language he does not understand in their presence. The subtleties and differences in the language that we speak can unite, as well as distinguish us.

Language nurtures and alienates; it is at the same time a homecoming and foreign or even enemy territory. How do we come to terms with the foreignness of language? Walter Benjamin saw the task of a translator as revealing the untranslatability of language and as a coming to terms with the foreignness of language—advancing the idea of exile as the first metaphor for language and the human condition. Similarly Julia Kristeva professes that "[s]peaking an 'other language' . . . is quite simply the minimum and primary condition of being alive." Our human condition is marked by exile. We all speak a foreign language.

You have written that your maternal language, Western Armenian, is disappearing. Would you say that your wall drawings, such as fig. a, a comme alphabet (2009-ongoing) and Words Recollected (2010-ongoing) are addressing—or grieving—this disappearance?

Armenian is a language I was never taught, that I speak with a grammar I make up and with a limited vocabulary. I speak Armenian, but I barely read or write it, hence very few new words are added to my basic vocabulary. I only use the language with my immediate family. My Armenian is, like Kristeva's Bulgarian, a maternal memory. In Intimate Revolt, Kristeva writes of "this maternal memory, this warm and still speaking cadaver, a body within my body, that resonates with infrasonic vibrations and data, stifled loves and flagrant conflicts." Exile always involves a shattering of the former body, of the old language; substituting it with another, more fragile, and which feels artificial.

Dutch is the language of my scholarly education, the language of my public (and intellectual) life, yet even when the foreigner (or diasporic subject) blends in perfectly with the host language, without forgetting the source language, the mother tongue, or only partially forgetting it, he is perceived as foreign because of this translation, which however perfect betrays a melody and a mentality that do not quite accord with the identity of the host. While aspiring to assimilate the new language absolutely, the foreigner injects it with the archaic rhythms and instinctual bases of his native idiom.