The person holding the sign was my expatriate uncle, a doctor and toxicologist with an original mind. As a child I used to hear the most amazing stories about him from my parents, he had always been a kind of mythical figure to me. Several years ago he contracted leukemia and underwent a stem-cell transplant with his own brother, my father, as the donor. He made a complete recovery. For me, an author of both novels and literary non-fiction, this was a good reason to write about him. So a year ago I had spent three months doing research in the northwest United States, just south of Canada, in the town where my uncle lives. Now the manuscript was finished. Although he hadn't actually asked if he could read it, it seemed like the right thing to do. I could've e-mailed him the text, because despite his age—nearly eighty—he was an avid Internet user. But I thought it would be better for us to go through the text together. There was a thick stack of printed paper in my suitcase. I had a feeling we might run into some problems.

We hugged. Lots of laughter. By now I knew my uncle well enough to tell that he was nervous. Laughing and gesturing, he explained that the sign 'PROTAGONIST' had to do with a message I had posted on Facebook, in which I told my friends, in English, that I was off to America for two weeks to go through my manuscript with the protagonist. I had always assumed it was a perfectly ordinary word, but my uncle, also one of my Facebook friends, had never heard it before. He has lived in the United States since 1953 and written numerous scientific publications in English, but this particular term was unfamiliar to him. "As long as I'm not the 'antagonist'," he said, which was typical of him: he had immediately gone and looked it up on the Dutch Wikipedia. When I later checked to see what he had found there, I read that the protagonist is the most fully developed character in a story. In the beginning he usually leads a fairly uneventful life, until halfway through he feels compelled to make a decision he cannot reverse. At the end of the story the protagonist has been changed by everything he has experienced.

The text of The Mythical Uncle—though I hadn't done it deliberately—seemed to follow this pattern. In the course of his life my uncle has made decisions that have had drastic consequences, not only for himself, but for others as well. All these decisions had to do with religion, because in addition to being a sharp-witted, eloquent, adventurous man, my uncle is also one hundred percent Calvinist. He has spent most of his life devoting himself to a religious denomination formed during World War II, just before the hongerwinter of 1944, when people in the Netherlands were eating tulip bulbs for lack of real food. At that time, of all times, there was a factional struggle within the Dutch Reformed Church and a group arose that called itself 'the Reformed Churches (Liberated).' My uncle, who came from a secular family, met a girl several years after the war whose parents had joined the Reformed Churches (Liberated). He subscribed to their brand of religion, and all the stringent rules that went along with it. When his girlfriend emigrated to America with her parents, he followed her, and they got married in their new country.

The problems I was now anticipating in reading through my manuscript with him had to do with my uncle's religious principles and the moral dilemmas they had posed. He had experienced a psychological change that I found very moving.

*

We crossed the border and headed for his town. I'd be staying in the same apartment I had rented the year before. I was feeling nervous too; much depended on the coming weeks. I had successfully completed nearly all the phases of writing a work of literary non-fiction. My Dutch publisher, who had rejected an earlier book proposal, was enthusiastic about this topic. The Fund for Investigative Journalism had given me a research grant, most of which I would have to pay back out of my royalties. I had worked on the book fulltime for more than a year, and my savings were greatly depleted. My publisher had already read and commented on the first draft of the manuscript, after which I had done a second, improved version. This was the last, crucial phase.

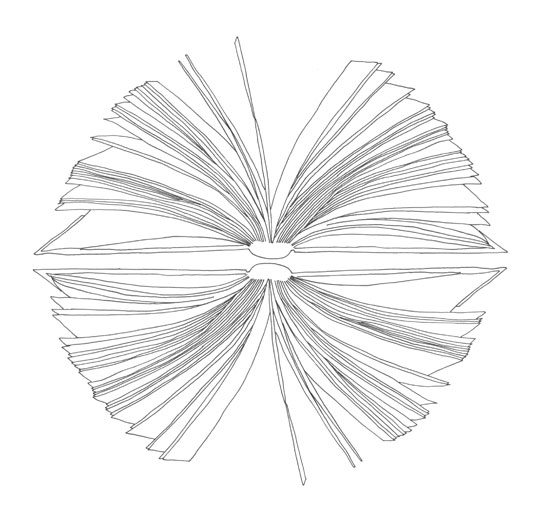

Why had I set myself the task of writing a non-fiction book? When you write fiction, you have complete freedom, which is exactly what I've always loved about it. 'Real life' isn't as easy; my dealings with other people have often led to disappointment. I tend to forget that not everyone thinks and acts the way I do, so it is essential for me to create characters in the seclusion of my workroom whose behavior I do understand. A fellow writer once commented that the process of writing a novel—and I've written six—is comparable to painting. You start with nothing and then build it up, layer by layer. Writing non-fiction, on the other hand, is more like sculpting: you start by gathering together a large 'chunk' of material, then chip away until only the essence remains and hope to evoke the same sense of amazement in the reader that you yourself experienced as the chunk of material was growing.

Even though I consider myself primarily a fiction writer, I find it important now and then to employ the chipping method. As a writer you can't always sit in your workroom or hang out in cafés with people who think exactly the same way about everything as you do. Your knowledge of the world and human behavior must be continually nourished, preferably in the field; that's why I like to alternate writing fiction with non-fiction. In some way it makes the literary process easier, because reality is always giving you unexpected gifts. You just have to be open to them, and then use them as you see fit. At the same time there is the disadvantage that you become dependent on chance. In this particular case, during the three months that I had lived in the little American town, something happened at the end of my stay that was so dramatic, you wouldn't have the nerve to include in a novel. It would seem too implausible.

*

Another of my non-fiction books that is particularly important to me was published in 2006. It is about my experiences living with the Roma (Gypsies) in Romania, where I've made numerous visits on and off since 1990. From the very beginning it seemed only logical that I stay in Romani homes, even if they were shacks made of sticks, mud and asphalt paper. At a certain point I discovered that not all writers necessarily felt they had to work that way. When I was back in the Netherlands I was asked whether I had spoken with 'real Roma'. Those who asked had assumed I'd been sitting in a hotel room reading reports from relief agencies and only occasionally, accompanied by interpreters, aid workers or politicians, ventured into a Roma neighborhood. The reality couldn't have been more different: I had taught myself Romanian, slept in poor people's beds and bumped along in their wooden carts behind scrawny horses. In the 1990s there were hardly any aid workers or politicians interested in Roma; it wasn't until the year 2000 that NGO reports first began to appear.

After I had shown an early draft of The Mythical Uncle to my publisher, he reacted in more or less the same way as those who hadn't expected me to immerse myself so deeply in the world of the Roma. He didn't quite understand it, he said. He knew me as more of a bohemian, a free spirit. Someone who hung out with Roma, sat around wood fires and traipsed through garbage dumps. And now here I was in America, sitting through two hour-and-a-half church services a week for three whole months and writing about how sinful it was to work or shop on Sunday?

Actually, I had incorporated two different kinds of data in the manuscript. My uncle's life story, which he had told me in a series of lengthy interviews, I had converted into what is known as 'faction.' Scenes I felt were representative of certain periods in his life I had depicted using novelistic techniques. I had crawled inside his head, so to speak, and made him think the way I think he does. As a reader you see that—like all of us—he is merely doing what he thinks is best. Since 'what is best' is different for everyone, there can sometimes be a conflict of interests. I wasn't concerned with whether or not everything had gone exactly the way I described it; what mattered to me was that these factional chapters based on my uncle's tribulations give the reader a glimpse of the bigger picture: the emigration of Dutch citizens in the postwar years and their efforts to make a home for themselves in their new country.

My publisher's astonishment had mostly to do with my own experiences in modern-day America, which I recorded in alternating chapters. Among other things I describe the weekly church services I attended: I had always taken it for granted that I'd spend my Sundays just like the rest of the family. I listened to their views, but never opposed them. What I didn't realize at the time was that I might owe my readers an explanation for my silence. Nowadays there is a great aversion in the Netherlands, certainly in Amsterdam cultural circles, to religion and religious followers. I don't share that aversion. We each have our own way of transcending the banality of everyday life; religiosity is just one example. I enjoy the challenge of being involved in a world that is not my own. After talking this over with my publisher, I decided to add two sentences at the beginning of the book in which I explain that I don't really understand why I could be open to the Roma in Romania—and, on my other travels, to Tuaregs in Mali and Muslims and Hindus in India—but not to my Christian countrymen living in the United States. Everything that followed suddenly became clearer. Two sentences, roughly fifty words, had a significant impact on the reader's perception of the next ninety thousand.

*

The first time I went to America, to spend three months in the small town where my uncle lived, I had brought him my book about the Romanian Roma, as a gift. He immediately began reading it. Not a little each day—no, he stayed up till deep in the night reading all 335 pages. Later he told me that you could see the whole of mankind reflected in that book, mankind after the Fall. The book, he felt, was about human behavior under extreme circumstances. He told me about other books he had recently read: the autobiographies of G.W. Bush and Andre Agassi, the memoirs of Sarah Palin. In his study, which was larger than my entire apartment in Amsterdam, were shelves filled with medical books, books about the history of the region where he lived, historical novels, fictionalized wartime accounts and an impressive number of antique Bibles.

Clearly, my uncle was a man who knew the power of the written word. He had spoken to journalists throughout his career. This made him a very different subject for me than the Romanian Roma. Many of the Roma with whom I had—and still have—contact were illiterate. They didn't realize that everything they did and everything they said to me would determine the image my Dutch readers had of them. When a pair of desperate Roma parents tried to sell me their baby in the early 1990s, they certainly weren't thinking: we better watch out, or they'll think we're all child traffickers. My educated uncle, on the other hand, was constantly aware that I was doing research for a book. We talked about it all the time. I recorded our interviews on a voice recorder that lay between us on the table.

Now, during this second visit, I thought: I have to make sure my uncle doesn't read the whole draft in one sitting. I wanted him to calmly absorb the contents, so I gave him one or two chapters at a time. After five chapters he remarked that the process of writing a book like this reminded him of his own scientific research. You start out with a specific goal, you want to know more about a stem-cell transplant. So you open a particular door. Behind that door are other doors, which you open one by one, and behind those doors you discover people and topics you had never expected to find. In this way you continue to build and make discoveries that are perhaps quite different than those you had thought you would make.

A week later, shortly after I had given him two more chapters, I paid a visit to his eldest daughter, who also plays a role in the book. At first everything was fine, but all of a sudden she started crying. Her parents were hardly sleeping, she told me. They looked awful. The manuscript was a disaster, they had said, the whole family would have to move. I was stunned. I couldn't imagine there was anything controversial in those last two chapters. "The whole book is full of gossip about our churches," my cousin sobbed. "We all thought you were a nice person, but you're not. You're just making fun of our religion!"

*

The mood had changed. There was now enormous tension between me and my American family. It was a writer's nightmare; the quality of my work was at stake. I tried to think of other writers who had been in a similar situation. Everyone, I soon discovered. Publishing a book almost always leads to trouble. My Croatian friend, the writer Dubravka Ugrešić, even had to move to another country, the Netherlands, because at a certain point her work was considered unacceptable by the cultural elite in Zagreb. And it wasn't for nothing that the South African author J.M. Coetzee settled in Australia several years ago. I myself had recently read Vie Française by Jean-Paul Dubois and Shadow Tag by Louise Erdrich, both novels with an autobiographical slant that could never have been published as non-fiction, because it would've hurt too many people.

In the meantime, I still had my American family to deal with. The situation undoubtedly confirmed for them what they were told twice a week on Sunday, that Man is accountable for everything bad. Everything good, on the other hand, comes from the Lord. The basic concept of most orthodox forms of Calvinism is not love, but sin. Virtually every sermon ends with this message; awareness of one's own sinfulness runs deep in followers of these religious movements. At the time when my uncle and aunt emigrated to America, most Dutch Protestants felt this way, but in the following decades our country became a place where the church was one of the institutions people distrusted most. Nowadays hardly anyone in the Netherlands goes to church every Sunday.

More discussions, more tension. I tried to be as open as possible, but at the same time I was fighting for my book. My uncle and I spoke about the dramatic events of the previous year, which had to do with my eldest cousin's terminally ill boyfriend. He had set off a chain of disasters after smoking medical cannabis in bed. My uncle, who had never before wanted to talk about this man with me, had gone through a long, inner struggle until finally he realized that he would have to accept him. But apparently this wasn't the most painful part of my manuscript; what hurt my family most was what I had written about how the members of the various congregations were constantly keeping an eye on each other. My uncle had no objection to the fictionalized chapters about his own life; he understood that I had taken a certain poetic license. But my observations about church life today were totally unacceptable. "What you say is true," he said, "but the truth doesn't always have to be put down in writing." He wanted me to change all the names in the book, including the names of institutions, denominations and the town he lived in. What's more, the book had to be published as fiction, with the word 'novel' featured prominently on the cover.

Now I was the one losing sleep. Maybe it was just a question of language, I thought. If you leave the Netherlands in 1953 and English becomes the language you think and read in, you aren't likely to keep up with linguistic developments in your native tongue. I had even included a paragraph about this in the book, because I'd noticed that my uncle and aunt made funny little mistakes when they spoke Dutch. Sometimes they would ask me if a particular word was still 'in fashion.' Sentences in the manuscript that I had intended as neutral, or even positive, they took as negative. For instance, I had written that they lived 'with great gusto,' by which I meant that they get great pleasure from a delicious meal, or a beautiful old tree. But they interpreted it to mean that they were greedy.

I decided to sacrifice a few anecdotes. But it seemed too easy to me to suddenly start calling this book a novel. If you're going to write a novel, you have to decide that beforehand, as Dubois and Erdrich did. To write a work of non-fiction and then call it a novel felt like an act of cowardice, as if I were taking refuge behind some sort of parliamentary immunity. 'Don't worry, it's just fiction!'

*

I went back to Amsterdam. What now? I kept thinking of what a friend of mine, another writer, once said to me. We had been talking about a colleague, and my friend said: "She's not a kind person. But she's a darn good writer." I couldn't get her words out of my mind. What about me? Did I want to be an unkind, even bad person who had written a good book? Or a good person with a bad book to my name? Integrity is important to me. In fact, all my novels are about how one should live one's life. At the same time, I have a passion for good literature. Should I comply with the wishes of my uncle, who had offered me three months of hospitality and whose daughters had become like sisters to me? He had the same blood and bone marrow as my father; even their blood type was the same since the transplant. On the other hand, he knew my background, he knew what he was getting into long before we started. Should I have listened to those who had warned me never, ever to write about relatives who were still alive?

I discussed it with an older friend whom I've known for nearly twenty-five years. "If somebody had written a good book about me, I wouldn't like it either," he said with a wink. We both knew exactly what kind of life he had led, and how someone very dear to him had suffered for it. A good book isn't afraid to reveal facts. If we ourselves are the subject of that book, we need a certain magnanimity to be able to give it our blessing. Most people who are written about during their lifetime hope there won't be too many unpleasant revelations. But a writer's job is to get below the surface, right down to the bones. Bad books written by good people almost always disappear into oblivion – that is, if they ever even make it to the publishers'. Good books by nasty people have a better chance of survival. A nasty person with a good book is usually settling some kind of score. Readers love that.

Jeanette Winterson couldn't publish her wonderful book Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal until after the death of her cold, heartless stepmother. I don't know what sort of person Winterson is, and I don't really care. As a reader, all that matters to me is her book. She describes in Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal how, at the age of twenty-four, after the publication of Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit—which was also about her youth, but which she had designated as a 'novel'—she called her stepmother from a phone booth, hoping the woman might have something positive to say about the book. But her stepmother was furious, bitter. Not the type of person you want to publish non-fiction about during her lifetime.

As far as The Mythical Uncle was concerned: I agreed to change the first names of my characters. It made no difference to the content of the story. Changing the last names of secondary characters would make no difference either, so I agreed to that as well. My biggest dilemma was what to do about my uncle's last name. I had originally been motivated to write the book after his stem-cell transplant, for which my father had been the donor. Brothers generally share the same last name. In this case, their name was also my name, because in the Netherlands many women keep their maiden name after they're married. It's the name I use when I write, too. I wasn't prepared to use a pseudonym for this book.

After considerable thought I came up with a solution, one that would give my uncle a slightly different identity. I inserted a paragraph in which I wrote that after he arrived in America he was annoyed by the way Americans pronounced his Dutch surname, so he had it changed to a name that sounded almost the same in American English as it did in Dutch. Once again, I had introduced a fictional element into a non-fictional work, but I still didn't have the feeling I was violating the foundation of the book: the true story.

It didn't take me long to decide whether or not to change the names of the denominations. Religious denominations are institutions; it would be ludicrous to give them fictitious names. The historical value of the book would be reduced to zero. Besides, these denominations weren't treating me very kindly either, especially the most orthodox. They saw themselves as God's chosen people; a European individualist like me would end up in Hell.

What worried me most was the name of my uncle's town. The book is specifically about that place, about the large percentage of people of Dutch descent who live there and the influence their mentality has had on town life. If I changed the name of the town, what would I do about the bibliography? The name appears in the titles of several of the works I had consulted. Was I supposed to start changing the titles of other people's books? I asked the director of the Fund for Investigative Journalism for advice. She didn't object to me changing the name of the town, but had no solution for the bibliography. One thing she was very clear about: the Foundation supported only non-fiction projects. Calling the book a novel was out of the question.

It was my publisher's opinion that mattered to me most. He thought long and hard, and finally reached the conclusion that I shouldn't change the name of the town. He could find nothing injurious in the manuscript, I had handled my subject with respect, so what was the problem? If I needed legal advice, he could arrange it.

*

There had to be a middle ground between 'a good person with a bad book' and 'a bad person with a good book.' But what? My uncle and I have a completely different way of thinking. For him, the Bible is the infallible word of God. If that book says the earth was created in six days, then the earth was created in six days. As an author and reader of literary novels I'm used to the opposite: for me, a well-written novel is one with underlying layers of meaning that allow for different interpretations.

I've always been inspired by the work of Michel de Montaigne. His tone is never ironic, or rancorous, but one of amazement. In his Essays, written in 16th-century France, Montaigne tries to observe and analyze his subjects as objectively as possible. The reader is then free to interpret these pieces any way he chooses.

I'm often reminded of two reviews I got on the same day about my Romania book. One critic thought it was too sentimental, the other found it too harsh. Everyone reads what they want to read; as a writer the most you can do is nibble away at other people's prejudices.

That is why, in the end, I decided to record my observations honestly, but at the same time to take the people I was writing about as seriously as possible, even if their ideas were diametrically opposed to mine. I've never been much of a polarizer: I want to know both sides of the story. If you grow up in a society where left and right, conservative and liberal, religious and non-religious are constantly at each other's throats, chances are your writing will reflect this, with the result that your books will either glorify or undermine. But I grew up in the Netherlands, at a time when people still believed in consensus. In recent years, under the influence of certain—in my opinion extremely dangerous—politicians, Dutch society has hardened.

My uncle's request, that I change the name of his town, proved impossible. It would have attracted too much attention. The question would've come up in every interview and review: what was so terrible about that place that the author had to change the name? The result: dubious discussions. I could already imagine the blogs: 'She writes about Middletown, but what she really means is...', followed by a negative characterization of the real place. There are already too many facetious remarks on the Internet about the strong Calvinist ethic in that town. And the ironic approach was exactly what I wanted to avoid: with a subject like this, irony is the easy way out.

In order for a novel to be convincing, a writer has to pull out all the stops. By contrast, a book about something that the reader knows really happened already has a certain impact. A writer of non-fiction is obliged to work with more subtlety and precision. Up until the very last version of The Mythical Uncle, I was busy deleting one word and substituting it with another. The choice between two synonyms, however close in meaning, can make all the difference. I chipped away painstakingly at my sculpture with a tiny chisel, smoothing and polishing until I felt it would wink at some readers and nod approvingly at others.

Looking back, I think it was wise not to change the name of the town. If I had, my uncle would've been even more vulnerable. To some extent, this is already the case. Throughout the book the reader does his best to try and get to know my uncle, to understand—though not necessarily agree with—his way of thinking and the choices he makes. He may even begin to like this man, whose ideas are so different from his own. Then he reaches the epilogue and discovers that the feelings aren't mutual: the protagonist prefers to remain nameless. "I thought he was such a nice guy," one journalist said to me. "But then at the end of the book it turns out he wants his name changed. I didn't get it. I started to think he wasn't so nice after all."

My father, one of the most important secondary characters, said he thought the book was written "with tenderness, toward everyone involved—including your uncle." And yet... It all went wrong in the end. In the final chapters in which I describe my experiences, I found myself unable to remain objective. Just before I was about to return to the Netherlands, it became known that my eldest cousin was caring for a terminally ill man, to whom she wasn't married, in her own home. Her congregation responded to this 'sin' by forcing her out. She was no longer welcome in church. This went beyond what I was willing to tolerate, and at that point in the book there was no room for subtlety. I explain this in the epilogue, which, added to the fact that I had left the name of his town intact, may be part of the reason the protagonist has stopped answering my emails.

I had done my best to write a good book without becoming a bad person. But in the eyes of my family, I'd apparently failed. When I went on Facebook recently I discovered that my uncle and several of my cousins – even some of the grandchildren – had unfriended me.