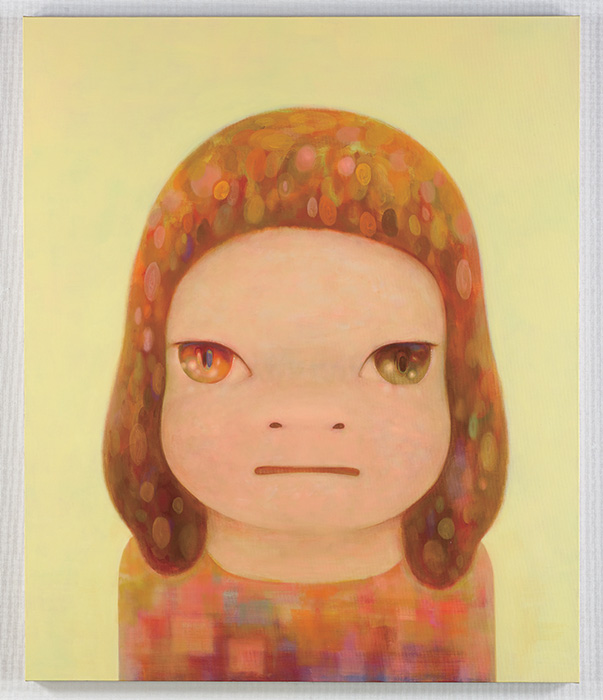

Oddly Cozy. Photo by Keizo Kioku. Copyright Yoshitomo Nara. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery, NY.

The 3.11 disaster, as the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami is known in Japan, was immensely traumatic to the country and its people. The combined catastrophes of the earthquake, tsunami, and the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant killed more than twenty thousand people and more than three hundred thousand people were evacuated. It was the biggest national crisis since World War II, one that has led the Japanese people into a period of fundamental reconstruction of their lives.

In November 2013, when this interview was conducted, more than two hundred and eighty thousand people were still displaced and many problems in the disaster-stricken area remain unresolved. 'Yet,' as Hideo Furukawa, a Fukushima-born writer, cautiously says during the course of this interview, 'the incident is about to be forgotten, or they pretend nothing has happened.'

In the past three years, the country has apparently recovered well from the disaster. But the 'recovery' or sense of recovery promoted by the government and media may have conversely blinded people to lingering issues and painful lessons that have yet to be considered. The effects of the deep trauma worry Furukawa on many levels: He observed the disaster and the problems it created, and warns that if left unexamined they could continue to harm the nation and its people in a real sense. Out of this deep concern, he has written his latest story, 'Footprints,' for Asymptote, and conducted this interview.

Initially, Asymptote requested Furukawa be interviewed himself to talk about his work, and his new story. He declined, and suggested that he instead conduct an interview with another artist: he asked that it be Yoshitomo Nara.

Yoshitomo Nara, an Aomori-born artist, is yet another influential figure who has visited and been active in the disaster-stricken area. In this casual-but-sincere dialogue-styled interview held in Shincho-sha, Tokyo, the two Tohoku-born artists intensely talked about their art, as well as many concerns they share, from the effects of getting older to the effects of 3.11.

Here, Asymptote presents an excerpt from their two-hour-long intimate conversation.

—Sayuri Okamoto

Topic 1: The Artist and Aging

Furukawa: Let me begin the interview with a question about aging. We were chatting about your eyesight changing with age. Does that affect your work?

Nara: My physical power and ability have decayed, of course, but I've obtained new, far-sighted eyes in exchange. Aging does my work good in this sense. I see a big picture, instead of the details I used to focus on with my younger eyes. I enjoy the bird's-eye view of being an older man. And I don't need reading glasses yet!

Furukawa: Has your work changed as your eyesight has changed with age?

Nara: It has, in a good sense. I care now for the core of the work. When I was young, I used to split hairs when I was drawing. Now I know it's best to work in a way that befits your faculties at the time. Henri Matisse is a good example. He used to make small tableaus when he was young. When he was older, however, he started painting on big canvases, so big you couldn't grasp the whole picture unless you saw them from afar. By contrast, Salvador Dali kept drawing the same kind of intricate painting, which he had characteristically produced in his youth, as he aged―even wearing reading glasses. They aren't good at all.

Furukawa: I guess he tried to replicate his younger self and work.

Nara: Yes, and that's why his later works don't appeal to me as much. It's no use trying to draw the same kind of work you made in your youth, especially if you need reading glasses to do so.

Furukawa: Speaking of the eyes, critics say that the eyes of your characters have changed. Does it have something to do with your own far-sightedness?

Nara: Now I see myself in relation to my paintings as a creator and part of the audience at the same time. I used to work as both a painter and 'the' only member of the audience, in a kind of one-to-one manner. Having lost my perfect eyesight—or having gained new sight—I started regarding myself just as one part of my audience. I feel my eyes among the other hundreds looking at me. They say human eyes are the mirror of the soul, and I used to draw them too carelessly. Say, to express the anger, I just drew some triangular eyes. I drew obviously-angry eyes, projected my anger there, and somehow released my pent-up emotions. About ten years ago, however, I became more interested in expressing complex feelings in a more complex way. I began to stop and think, to take a breath before letting everything out. That might be another effect of aging.

Furukawa: I guess I know what you mean. I've equated speediness with creativity up until a couple years ago, but I don't rush to make quick decisions nowadays. I'm less inclined to judge things by intuition.

Nara: Intuition has its own weakness. I enjoyed my intuitive power when I was young, too, though.

Furukawa: Now that I'm older I feel my period of rebelliousness is over, at last. I enjoy being immersed in someone's world. I even enjoy reading the old masterpieces, which I couldn't have empathized with when I was young.

Nara: I know what you mean. I've become more and more aware of the power of art produced in a time when all that mattered was immediate human relations. In comparison, contemporary works seem to have little power because they are made too instantly.

Okamoto: Can you say more about what you mean by 'all that mattered was immediate human relations'?

Nara: I mean, when our ancestors didn't have electricity, when they didn't even know where Europe was, or what's going on in the U.S., what's happening in Egypt. In short, a small world.

Okamoto: A small world within your reach.

Nara: Yes. There shouldn't be any difference between people from earlier times and us when it comes to the amount of information your brain can process. They lived in a small world without any broader, worldwide concerns, such as international politics and economy; they must have had plenty of room in their brains to care more about the things that were close to them. For example, when I examine Leonardo da Vinci's drawings, I always feel he was able to produce those works because of the time. Ancient Greek art makes me feel the same. Regardless of the genre, whether it's writing or painting, the most perfect and universal art emerges when the form is first established.

Furukawa: The very first form is natural and just so apt to survive.

Nara: Right. I feel all the more keenly the need for my approach to have the natural simplicity of a painter living in our complex world. I know I can't draw like ancient painters or Leonardo, but I mustn't forget those pioneering painters' spirits and their ways of approaching the world.

Furukawa: I guess it's a kind of destiny for an artist to feel that way. Painting has a long history, and the very history of the genre urges you always to bear in mind its history and origins. I know the feeling as a writer, too. The more you work, the more you feel the need to approach the origins with a fundamental question: 'What is painting?'

Nara: The older the work is, the more it appeals to me. The power of old works might owe to their 'naturalness.' Painters must have naturally breathed in the air and the wants of their time, then breathed out the reply through their work; again, naturally. We can't tell what our time wants because of the noise surrounding us. To make matters worse, there is a system pushing artists to produce false 'wants' in our time. That's one of the factors that make more of what I call noise.

Furukawa: With too much noise and focused, micro-scoped concerns, we might have lost the big picture of our time and world. We all need to be a bit far-sighted like you, don't we?

Nara: (laughs)

Furukawa: You are known for big projects that involve hundreds of volunteers and staff. When you paint on a smaller scale do you tend to seclude yourself from the outside world? Or do you prefer to have input from others, as you do in your big projects?

Nara: No matter the size of the project, you can't achieve a satisfying result unless you really work hard all by yourself, in the end. I enjoyed my past big projects and collaborations, but there have always been gaps between me and the volunteers or staff gathered for 'my' project. They work on a plan and timetable. They know what to do today and when to call it a day. It's easy to be at their pace, in a way. But I'm the type of person who wants to work as much as possible in a day when I'm in a working mood. When I feel I can make something more, I want to work more no matter the time, no matter the schedule. In the end, I'm not a teamwork type of person. I have no 'real or personal life' outside of my working life, like other people may have. Or at least, I'm not good at 'enjoying my life' after I've finished the work.

Topic 2: The Self and the Power of Imagination.

Furukawa: You studied and lived in Germany for 12 years. Did you have an idea of what would happen during your time there before you went?

Nara: Not at all! I went there when I was 28 years old. I was in my last year of art college, and was teaching art to high school students. As I did, I gradually felt that it was not them but me who must be taught art. I chose Germany just by chance. In fact, I could have gone to London instead. I can't imagine what my life would be had I gone to London at that time, when the city was a mecca of young, energetic artists. For one reason or another, I ended up living in Germany for 12 years. I became literally 'alone' there. It strongly reminded me of the memory of my lonely childhood. I felt the city's (Düsseldorf) cold and darkness, just like my hometown, and the atmosphere there reinforced my tendency to seclude myself from the outer world. It helped me to remember the boy-me's feelings from back in my hometown, too. So I started talking with the 7- or 8-year-old boy-me in Aomori and the 28-year-old current-me in Germany, beyond the time-gap of 20 years, and the thousands of kilometers of distance between the countries. The result of the conversation was so obvious: what I drew changed drastically.

Furukawa: Only after a real conversation with her or himself can an artist establish their style, an original way of expression.

Nara: Maybe so. To be an artist, one might need to be deprived a bit of what he or she has taken for granted: accessibility to things and people, including language and a means of communication. At least, I needed a setting which would allow me to isolate myself from others to have a real conversation with the inner-me, in my case. I found my style only after living in solitude. I couldn't have achieved my style without a good setting, without the help of the place and circumstances.

Furukawa: Solitude. Yes, you must apply yourself closely to your work. In the same sense, you shouldn't think too much about your audience. I always tell myself that I should have, ideally, my own creator's point of view and that of the audience at the same time to keep a kind of well-balanced solitude.

Nara: Ideally, yes. But haven't you ever been flattered and encouraged to go on, especially at the early stage of your creative career? At times, you need others' points of view. In my case, I decided to be a painter when a friend who saw my drawings said, 'You're good, Nara!' (Laughs.)

Furukawa: But being 'good' is not a crucial point when we value an artist. There are hundreds of examples of not-good-but-appealing artists and works in the history of art and literature. Those are the works and people who have something particular only to them, and that very particularity or singularity lets them survive over the centuries.

Nara: I would call the particularity a power of image that the work conveys. In the case of written work, no matter if it's written in Japanese or English or Chinese, it's the power of the image the story evokes in the readers' mind.

Furukawa: You mean the power of something 'beyond the surface'?

Nara: Yes. Otherwise, you can't explain why you're moved when you read a piece in translation. A story imprints on your mind an image that is beyond the language. We say, 'I was moved, though I can't explain how and why,' don't we? That happens often with works that are so-called masterpieces. And that beyond-words appeal is, for me, the power of the imagery that the story delivers.

Furukawa: What about the words you sometimes insert in your drawings?

Nara: I guess they condense and represent all the images I conceive of. When I write 'rock' in my work, I'm speaking to people who might share a part of the images that I have around the word 'rock.' I suppose people in my generation sometimes imagine those who love the same kind of rock music I love are the ones with whom I want to share my imagination underlying that word. It depends. A word is a kind of a key to a door which opens and leads to my world of imagination. I know it reaches some people, but I also know that it doesn't ring a bell with others.

Furukawa: Can you tell a little about the sources of your imagination?

Nara: I remember a lot of the picture books and music records I devoured in my youth. I was born and grew up in a rural area in Aomori. I didn't have much opportunity to see 'real' works of art, especially western art or the works that were made under western influence. I mean, we did have a lot of Buddhist art in my region, but they weren't 'art' to me at that time. So the visual images I enjoyed the most were picture books. Not manga, especially. You wouldn't read manga with much imagination. You'd read them passively, looking forward only to see what might come next. With picture books, on the other hand, you'd work your imagination a lot more starting from a picture, and little words would suddenly come along with it. The more you look into the picture the more you think and the more your imaginary world expands.

As for records, I bought a lot of imported records because they were inexpensive even for someone my age. But, you know, I couldn't read the jacket cover of the thing I'd just purchased! Yet I pulled the record out of the cover and started listening with the cover in my hand. It got my imagination moving a lot and gradually I started picking up words. Little by little, I constructed the world of the record using imagination. I think I trained my imagination through the picture books and records, without knowing I was doing so.

Furukawa: I know what you mean from my own experience. As you know, I was born and grew up in Koriyama, a provincial city in Fukushima prefecture. Looking back, I remember that those 'foreign' things like records and books came without any kind of Japanese 'footnotes' attached. Something 'foreign' came directly into our lives with no filter and left a strong impact on our adolescence, a crucial time for our character-building.

Nara: You are where you were born and grew up! My hometown in Aomori is known for its severe cold and heavy snow. You just endure the depressing season. You wait and wait and wait for a spring to come and when the spring finally comes, you learn that the season of joy comes only if you withstand the hard season. You repeat it every year, and your body remembers the lesson: 'If you endure, spring will certainly come.'

Topic 3: Artist and '3.11' (Tohoku Great Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011)

*Both Nara and Furukawa are from the Tohoku region, Aomori and Fukushima, respectively.

Furukawa: I was shocked by the gigantic bronze sculptures you presented in your exhibition in 2012. It was your first big exhibition after 3.11. What was your initial reaction to the disaster?

Nara: I became unable to draw. I guess everyone in Japan went through the same kind of emotional experience: I was so depressed that I couldn't help feeling that what I'd been doing was totally meaningless and useless. No one needs art in an extreme situation, after all. People don't think of art unless they are living with a certain mental and physical richness. I felt my powerlessness as an artist in an extreme situation and became unable to produce a single picture, no matter how much I struggled. I knew, however, that all I have is art. What I could do a little better than other people was draw. So I decided to prepare a piece for people who would have wanted it when their lives returned to normal: I took that as my role as an artist. I thought I should prepare the work for a future need. I told myself that I should devote myself to that mission. But I couldn't draw, no matter how much I encouraged myself.

Furukawa: Did you start making sculpture as a result of being unable to draw after 3.11? Or did you start it before the incident?

Nara: I'd been working on ceramics before 3.11. You could call it a metaphorical preceding, a 'self-kneading' process before I began working with the bronze. When at a certain point in my career I saw that my position as a certain kind of artist was somewhat fixed and secured, I felt something was wrong. There seemed to be a division between artists who were successful and unsuccessful, and that society had drawn lines that determine what you could do based on this kind of label. I felt uncomfortable with being given a certain label, whether it was positive or negative. And I remembered that I'd long forgotten how I had started my career. I realized that I'd long neglected the 'conversation with myself,' which had been the foundation of my creative activity. So I quit collaboration works and started working with ceramics to restart the conversation.

Furukawa: Why ceramics?

Nara: I can have the material there before me, to begin with. I have a thing to touch and 'knead.' To knead means to think by using the hands. My intuition told me to think by hand. I guess I wanted to go back to a point where I could communicate with my childhood memory again. As a child, I had played with clay and that was my very first hand-craft experience. I had kneaded clay, or sometimes my own droppings too, maybe, before learning to draw and other stuff. I guess I wanted to go back to that 'origin' of the pleasure of using my hands, of making something that escapes evaluation. Having done so, I then washed my hands of ceramics and shifted to bronze. I couldn't concentrate on my thinking-by-hand, after all. You need to learn and acquire a certain technique to make, say, a clay pot, and the idea of learning a new technique disturbed me in a way. I just wanted to put all my energy into hand-thinking, and I began to work on a massive lump of clay to make bronze sculptures. It helped: I accordingly recovered my hands for painting through this process.

Okamoto: What about you, Furukawa-san?

Furukawa: I couldn't write after 3.11 either. I didn't know what to write. You know, one needs time to read a book, but people didn't have time to spare for a book. They didn't need a book. I strongly felt that a writer was a useless being vis-à-vis such a disaster. I knew money was the most immediate need, but I didn't have any, and I didn't have political power to move big money either.

After a while I started doing a couple of experiments to grope for my own way as a person, and then as a writer. For instance, I went to the disaster-stricken area to see whether the immediate, on-the-spot reactions or words of mine there could be a short-story-substitute: a kind of new form of literature. I had three stories in hand around 3.11. I tried to continue and ended up with chaotic results. None of them could stand or be worthy as a piece of work after the disaster. I learned that my previous way of writing wouldn't work anymore.

Just like you Nara-san, I started talking with myself. I thought hard about the fact that I was a Fukushiman, born and bred. I tried to face the very fact that I was born and grew up in Fukushima, and it was my hometown, which now had a big, big problem. It took two years, in the end, till I became able to write again. Your bronze sculptures gave me a punch. I was shocked by the trace of your hands left on the surface of the works. The 'footprints' of your hands, the trace of you. Coincidentally, I started writing by hand, and leaving my footprints on paper, in 2012. I do half of my work by hand now. It feels like 'kneading' something by hand when I write with a pen; I feel a kind of responsibility of creation, more than I do when I write with a computer. It feels completely different from what I feel when I write with a machine. I'd draw a line if I made a mistake, instead of erasing what I've done. The line remains there and starts signaling something: my mistake and the deed and line of crossing-out remain in my sight. I keep writing, with the vestige of what I've done there in the corner of my eye. It affects you, really.

All in all, I struggled a lot after 3.11. I examined myself and my personal history, experimented with a documentary-like, dictation-like way of making a story in the very middle of the stricken area, and returned to the ancient tools of writing with pen and paper. Now after a lot of trial-and-error I can say that this 're-kneading' was a necessary process to recover myself, or to reconstruct my writing. I needed to face and talk with myself, no matter how tough it was.

Nara: I reckon you can't 'say' in a sense what you mean when you write with computer. A computer doesn't answer you. It can't be a conversation-partner substitute.

Furukawa: It can't! The letters that appear on the computer screen don't reflect what I've done. It doesn't show, for instance, the pressure of typing, which is equivalent to the strength of brushstroke when you write with a pen. It doesn't reveal the shape, size, and accent, the characteristics of my handwriting that I'd otherwise subconsciously show on paper.

Nara: With the computer, everything appears the same and flat, whatever you do. You also have the risk of deleting what you've just done by some accident. It'd never happen with a pen and paper.

Furukawa: The only thing I allow myself to expect is that something unexpected will happen or appear through the course of writing. This 'something unexpected,' which underlies the work in a piece of writing, should be independent from the writer, and only then does this 'something' emerge. In this way, the writer is simply a bridge between the piece and the image to be delivered. The writer wouldn't need to claim 'This is MY work. Read MY story.'

Nara: As for me, I don't care much about the audience and their reactions nowadays. It might be another effect of aging. What I wish now is that my works remain for, say, 200 years after my death. I hope they are strong enough, in various senses, to overcome the disappearance and death of the person who's created them. I consciously started thinking in this way after 3.11. I feel I don't need to show what I make now offhand. I don't have to do something 'new' either. Seen from the viewpoint of hundreds of years later, what we do in our life span of 70 or 80 years will not be a big deal. Our generation, even our time, might be categorized under the same name as Picasso's and Matisse's: only a few really strong works among all the others will survive.

Furukawa: It sounds like an objection to current or contemporary art.

Nara: So-called 'contemporary art', roughly speaking, still values immediacy, offhandedness, flexibility, change, up-to-date-ness, of the artist and their work. I feel the span of 'now' has become shorter and shorter, and artists must be very quick to catch up with 'now.' But I don't think it's those works that will survive, though I can't say what might. I'm still groping for my own way.

Furukawa: One positive, unexpected outcome of the 3.11 disaster was that it promoted another, or new, image of Japanese people to other countries. I think this was due simply to the fact that the disaster hit no other region but Tohoku, whose people are known for characteristics that surprised the foreign media: they are patient, extremely well-mannered, unselfish, cooperative, and so forth. Those virtues might not be the first image people in other countries have of 'Japanese' people before 3.11, though these are very Japanese in my view. Media, especially foreign media, had focused on big, peculiar cities such as Tokyo and Osaka and their people, and had a fixed idea of the Japanese. 3.11 managed to change it a bit, at the sacrifice of a great number of lives. It's a pity, though, that the change the incident brought about doesn't seem to have paved the new way for the country's direction.

Nara: It's simple. It's because politicians in power are from somewhere else, not Tohoku.

I was deeply moved too by how people behaved soon after 3.11, although I'd known that they possessed those virtues you've named. Apart from these virtues, there might have been another reason for their unselfish behavior or tolerance, namely, the elder generation who had known the War. I think people had learned the importance of patience, as well as how to behave during an emergency from the war generation. They had known extreme poverty, lack of foods and fuels, and the loss of home and family. Besides, Tohoku has been a poor region, and they have known how to live humbly, accepting the given situation. I don't think it's a 'new' aspect of Japanese people. They have been there, and have lived in that way. It is by chance that this came to light after 3.11.

Furukawa: They are tolerant, and so are you, Nara-san. You've been tolerant with the situation of being unable to paint. You stick to art despite the depression and trauma. We all might have needed to be under an extreme situation that urges us to be tolerant a little longer, so that Japan could change.

Nara: I agree.

Furukawa: We shouldn't have had to utter a word or pretend we were fine so soon. But many began to act 'just like before' in many cases. Many people did not see it as a chance to learn and obtain something really important. They started pretending 'nothing has changed,' and it was too early. The tragedy was doubled or tripled by how and how people reacted without having time to think.

Nara: Indeed. They might have pretended nothing has changed, but apparently there is a new phenomenon that occurred after 3.11. That is the attitude towards the border. You know, my studio in Tochigi is only 100 km from the troubled power plant. It's just next to Shirakawa in Fukushima. But apparently after the accident of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, there seems to be a clear mental division in people's mind: 'They are Fukushima. We are Tochigi,' though the distance from the power plant is the same.

Furukawa: That's labeling.

Nara: Yes, I know we do it and brand apples from my prefecture 'Aomori Ringo.' And although they make completely the same apples in Iwate, Aomori Ringo costs more than the others. We do the same with fish or rice, too. We brand the fish by the name of the port: Oma Tuna, for instance. If the same boat brings the same tuna to a non-famous port, the price of the tuna would be half.

Furukawa: Labeling, branding, or packaging, you name it, is a kind of mind control. It's a shared message or pretext, 'Let's not think about what's inside.' What we must have learned from 3.11 was the very danger of labeling. What we needed to do was not re-label things, not recover the labels we had before, but get rid of the labels and the idea of labeling, and learn to see what's inside with our own eyes. Unfortunately, it wasn't so easy to stop, think, and be free of this old habit. It's always easy to let someone evaluate and label something instead of doing it for yourself. I even feel scared about what feels like an accelerated tendency to begin 're-labeling' after 3.11.

Nara: I think that the most important things in life are those we cannot name or label. What obscures our vision and breaks our concentration on what is 'most important' is the labeling or branding. It's a way to call our attention to appearances, or superficial matters, not the contents or the inside where, and only where, what is 'most important' truly is.

Furukawa: That's the way of things in our time. People often don't bother to see what is 'most important' because it requires a lot of energy to face and then live together.

Nara: I sometimes wonder how life was when people were leading simpler lives with no electricity, cars, mobile phones, and so forth. It must have been inconvenient, but they must have been able to extend more imagination to others and be more creative, more patient, and more 'nature-friendly' in a real sense. It was good for me to experience a couple of days with no electricity or a mobile phone right after 3.11 despite the inconvenience. I remembered the darkness of a stormy night in my childhood. I was waiting in the dark for the power to be restored, hearing the thunder with my mother. I was looking at her profile lit by a candle while she was telling me a story about the war-time, when she heard the bomb attacks in the darkness with her mother. The power of darkness. Without any power in my mobile phone, I also remembered the anxious, but somewhat warm feeling of thinking of someone without being able to talk to them with a convenient gadget. I think our sensitivity to others and nature might be dulled by these tools of convenience. I'd be despised if a person from the Edo period were able to come and see me. They would say, 'How insensitive and self-centered you are!'

Okamoto: I would like to ask one more question before concluding the interview. Furukawa-san why did you invite Nara-san for this interview?

Furukawa: Nara-san is an independent artist. He has always been challenging something very big―that is, the definition of art itself―in a very original, innovative way. It must be tough to keep challenging like this alone, and I wanted to know part of the secret. That's the first reason. Secondly, he is also good at involving an incredible number of people in his projects, or just attracting so many people. He has a kind of magnetic force to which people are drawn. Yet he never works in a combative manner, or a fighting mood. This is the ideal way of creating. Serious, but casual. Haruki Murakami seems the same to me. I want to work like you, but I know I can't. I've just known that your way is ideal to me, and the fact that there is an artist who has been walking in my ideal way has encouraged me to go on. So, when Okamoto-san invited me to be interviewed by Asymptote, I replied that I would rather interview someone myself.

Okamoto: You immediately named Nara-san.

Furukawa: The great thing about Nara-san's artwork is that it appears to cross the border so casually, despite all the effort during the creation process. It's so accessible to everyone, no matter the language or cultural context.

Okamoto: Indeed. It's like Nara-san is creating the work and the translation at the same time all by himself.

Furukawa: Well, I don't agree with that idea. There is something untranslatable in his work, but that 'something' is beyond the idea of 'the border' itself, from the beginning. He has achieved it putting in tremendous effort, how much I can't even imagine. But his work doesn't reveal the struggle very much. Many people are ignorant of the gap between the friendly, kawaii aspects of his work and the struggle behind it. I didn't expect him to name what that 'something' is, but I wanted to listen to him to have a hint of what it might be.

Okamoto: I remember that you, Furukawa-san, said it was obvious that music was indispensable for Nara-san's art.

Nara: It's a pity, but some people can't really tell it. They might see only the surface. Doesn't it happen to you that you sometimes send a signal full of meaning, at least to you, but you worry nobody around you would get it? You feel like a clown. And sometimes I do in fact feel like a clown.

Furukawa: But you aren't afraid of being a clown, being hurt, in a way.

Nara: Not at all.

Furukawa: That's what I admire. I'm not like that. I tend to think that I'd rather stay home than go out in public and be misunderstood. I've tried to overcome this weakness, though.

Nara: How you'd be understood, or misunderstood, is predetermined by the nature of your work.

Furukawa: It might be the golden rule: One is destined to be subordinate to what she or he produces. I must remember it.

Nara: Me, too.